Discover more from The Cottage

London, 1995

The music played as the evangelist implored people to come forward for a blessing. The congregation was standing. Swaying really. To the music, to the rhythms of the Spirit present in our midst. Most people prayed with raised hands, reaching toward heaven begging for miracles to fall upon them from the skies. I was standing, too, my palms gently turned upward. Watching, perhaps waiting, wanting to fit in. Trying to find my place in the flood of emotions. People pressed by me to go to the altar to claim gifts of wholeness and holiness. At the front of the church, ushers aided those who had fainted with joy. Next to me, a man began crying, with audible sobbing. And then, much to my surprise, he started making guttural noises, animal-like sounds that resembled my dog’s response to the postman. In the early 1800s, people attending revivals in the backwoods of Kentucky and Tennessee reported episodes of “holy barking” among participants. Until then, I always thought those accounts were exaggerated. But it is different when a man in a business suit is worshiping in a church yapping like a terrier. I looked over at him just as his face was transfigured by ecstasy - and he collapsed to the floor. The ushers rushed over to check on him: “He’s fine,” one said. “More than fine,” the other replied smiling.

I wasn’t attending an American revival meeting. Nor was I visiting a Pentecostal church. Instead, this scene unfolded at an Anglican church, in a neo-Gothic building dating from nearly two centuries ago, with stained glass windows and graceful arches, this wild chaos was framed by an architecture of order, tradition, and stability.

When I left the service, a friendly greeter asked, “Did you enjoy the service here at Holy Trinity Brompton? People come from all over the world to be here! Did you receive a blessing?” I smiled. “Thank you for your hospitality,” I replied in a non-committal way. I didn’t tell her that I was working on a column about revivalism for the New York Times syndicate service. The fainting businessman, the strange angularity of New Testament miracles and elite Anglicanism, something didn’t really set well with me. I didn’t know what to say.

* * * * *

I haven’t thought about Holy Trinity Brompton for many years. But my visit there in 1995 is still vivid - the sounds, the smells, the images caught like photographs in my memory. A quarter of a century is a long time ago for an episode to remain so easy to recall. But then again, it is hard to forget a regular-looking businessman barking next to you in a the midst of Pentecostal fervor, especially when one is standing in a parish of the historically-crusty Church of England.

What brought it all back? That particular day?

Glenn Youngkin. The Republican businessman candidate for Virginia governor. This paragraph from an Associated Press story:

I remembered all the sweaty, speaking in tongues, spiritual chaos - the fainting, the weeping, the barking - and all those well-dressed, successful-looking parishioners shedding every ounce of British stiff-upper lip and tony Shakespearean worship in favor of revivalistic fervor from the Second Great Awakening in the American South.

When I read that paragraph, everything I’d been wondering about here in Virginia during this strange, surprisingly vague and politically slippery governor’s race clicked. And I’m not sure I like the way the pieces come together.

* * * * *

Before continuing, I’d like to make two things clear.

First, I’m comfortable discussing a politician’s religious views. Religion forms people morally and serves as the arbiter of conscience. Politicians should make their religious affiliations known, including how their personal faith influences the ways in which they deal with difficult issues - and how they themselves navigate their own disagreements with their faith traditions. There’s a contemporary history of doing this in American politics from John F. Kennedy through Jimmy Carter and Mario Cuomo to Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. Politicians who understand moral commitments and the ethical call of their vocations know it is important to address their faith. Religion shouldn’t be a prop to get votes. It provides an opportunity - and an angle of vision - to reflect on some of the deepest issues with which we struggle.

Second, reporting on a candidate’s religion should never be an uniformed or bigoted attack on any particular faith. Too many reporters and pundits don’t really understand theological complexity, historical developments, or the sociological dimensions of religion - and why and how people (including politicians) make particular moral choices vis-a-vis faith. Religion should be “fair game” to understand the character and political influences of any and every candidate; it isn’t “fair game” to stir up animus against someone’s prayer preferences or theological beliefs no matter how unfamiliar or exotic-seeming they may be to others.

With these two things in mind, I’ve been reluctant to talk about Glenn Youngkin and religion. Because of that day in 1995 at Holy Trinity Brompton. I worried that anything I might write could be construed as an attack on Pentecostalism, and on religious enthusiasm more generally.

I have no animus regarding Pentecostal Christianity. My much-admired late grandmother (who died when my father was six) was a Pentecostal evangelist. As a young woman, she converted in the great revivals of the 1920s. Her brother, my great-uncle, was a pastor ordained to the ministry by Aimee Semple McPherson herself. I treasure this family history and am deeply aware of the Pentecostal spirituality that has shaped my own Christian life. I’m not actually afraid of prophecy, tongues, healing, fainting in church, or any of those supernatural things - even “barking in the spirit.”

But I find myself with questions. Worrisome questions about Youngkin’s campaign, about how the particular practices and political twists of Holy Trinity Brompton have found their way to Virginia’s governor’s race.

* * * * *

My grandmother became a Pentecostal after her father was killed in a gruesome construction accident in the 1920s. He was a carpenter working on the steeple at a Catholic church when he fell to his death, leaving behind a widow and six children. In those days, there was no worker’s compensation and no welfare. They were plunged into poverty, living hand-to-mouth and on the charity of others. My grandmother - although a church had killed her father - found comfort in faith, in the new expression of Pentecostal religion.

She wasn’t alone. In the first years of the twentieth century, millions of people embraced an ecstatic form of Christianity that emphasized signs and wonders and promised new life through the power of the Holy Spirit. In those decades, Pentecostalism was racially diverse and appealed to the poor and outcast, those on the margins of society, a faith that found a home among (what one historian called) “the disinherited.” Although some critics thought that Pentecostalism served as a kind of “psychic adjustment” to economic inequality and injustice, others have pointed out that early Pentecostals bent social rules to remake racial and gender roles and formed a core constituency for the New Deal and other labor reform movements.

However radical early Pentecostalism was, over the decades, it changed and muted its more radical earthly expectations - eventually leaving the hope for justice in the hands of a miracle-giving God and succumbing to apocalyptic hopelessness in the political realm. Pentecostalism eventually became as racially segregated as the rest of American religion, and, although women originally held important roles in its leadership, Pentecostals came to embrace the same patriarchal forms as other fundamentalisms. Perhaps the last robust expression of left-wing Pentecostalism was birthed on the golden sands of California beaches in the 1960s during the Jesus Movement, where spiritual enthusiasm meshed with utopian countercultural dreams of searching baby boomers, where it was rebranded as “charismatic.”

Eventually, the charismatic movement made its way from the beaches to churches, the least likely of these receptive congregations being parishes of the Episcopal Church. Although there had been scattered episodes of Pentecostal expression in the mainline congregations through the late 1950s, the charismatic movement within denominations is typically traced to April 3, 1960, when Rev. Dennis Bennett, priest at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Van Nuys, testified to his parish that he’d been baptized by the Holy Spirit and invited them into the same experience. From there, the charismatic renewal movement spread throughout the Episcopal Church, eventually reaching - and transforming - two important congregations in northern Virginia - the Falls Church and Truro Church.

The encounter of Pentecostal enthusiasm and Episcopal upper-middle class respectability in the Virginia suburbs resulted in a new form of charismatic politics - a right-wing social activism based on a nostalgic longing for a Christian America and elite Republican social mores. While worship might be enthusiastic, and while parishioners might still hope for miraculous interventions in their personal lives by God, charismatic Episcopalians developed a distinctly political theology of order. The charismatic Episcopal churches of northern Virginia wooed and won hosts of conservative luminaries as members, including political operatives and Supreme Court justices like Oliver North and Clarence Thomas. To these Episcopalians, “renewal” meant experiential personal piety AND participation in an orderly body politic, where people submitted to biblical rules for good societies, and were overseen by godly male authorities in duly appointed roles. Thus, personal devotion (no matter how freely expressed) was always tempered and guided by wise patriarchs - those men in family, church, and government who ensured God’s will in all things.

That political vision meant being against abortion and other feminist concerns of women’s autonomy, health, and sexuality; opposition to marriage equality and the ordination of LGBTQ persons (and in favor of gay “conversion” therapy); standing against any and every human rights movement deemed to somehow be contrary to the teachings of the Bible; and celebrating American exceptionalism through a mighty military to defeat ungodly Communism. Everything was meant to restore American greatness - and secure political power to build the Kingdom of God on earth.

In one of the most ironic turns in American religion, Pentecostalism thus became a conservative social movement among upper-class white people - people with access to power and a global reach. They mobilized for the cause, meshing charismatic religion with a single political party - first through the politics of Reagan, then Bush, and finally, Trump (it is notable that almost all of Trump’s religious advisors were Pentecostal and charismatic Christians). And they worked on take-overs and schisms in the Episcopal Church - and then other Protestant denominations - through what were euphemistically termed “renewal” movements.

If you were inside these churches, you believed you were on the winning side of history, and that your Savior Jesus Christ would emerge as a triumphant Lord. Speaking in tongues, miraculous healings, swooning in the Spirit - these were the signs and wonders that anticipated his coming Reign and marked you as a citizen of that holy realm. In polite company, however, in a world shaped by aspirations of tolerance whose prestigious institutions were allergic to any sort of religion that smacked of fundamentalism and “holy rollers,” you needed to practice a kind of sacred subversion and disguise your true intentions. You knew when you were with other true believers; you learned how to pass in the halls of power. It was stealthy. Like being part of a secret army, a people on a mission sent by God to save America. The Episcopal church provided nice cover for religious conservatives who didn’t want to scare their enemies too much - until, of course, the Episcopal church outed them by ordaining a gay bishop and they broke away forming their own congregations while still trying to retain Anglican respectability.

But it was all a bit too late. The Trojan horse political movement worked. What had begun as a movement of the “disinherited” transformed itself into a religion of inheritance - a political movement to insure that the right Americans would always be beneficiaries of the nation’s wealth and privilege. The godly deserve no less.

* * * * *

How does a group maintain its spiritual vibrancy with a political agenda based on a quest for authoritarian order? With periodic revivals, of course.

And that’s where Holy Trinity Brompton comes into the story. In 1994, a new Pentecostal revival broke forth in a church in Toronto - thus earning the moniker “The Toronto Blessing” - and made its way across the Atlantic and landed at Holy Trinity. The church became Ground Zero of the revival, a powerful “third wave” of charismatic enthusiasm. This third wave movement emphasized spiritual warfare, the centrality of supernatural signs and wonders, and, perhaps more than anything else, a profound belief that the Spirit is transforming the true church - a purified church - into the actual Kingdom of God on earth. In short, this third wave Pentecostalism is not escapist - it is necessarily and purposefully political, complete with enemies (those who disagree with their theology), a miraculous tool-kit (financial prosperity, charismatic leaders), and a mission - to renew the entire globe on the basis of God’s order through the body of true believers. There is nothing shy about this, it is obvious to insiders, but to those unfamiliar with this history and language, it is hidden in plain sight.

And the faithful marched to a new crusading hymn:

Shine, Jesus, shine

Fill this land with the Father's glory

Blaze, Spirit, blaze

Set our hearts on fire

Flow, river, flow

Flood the nations with grace and mercy

Send forth your word

Lord, and let there be light

* * * * *

The revival of the 1990s - with its signs and wonders - was a spiritual jab in the arm reminding people of the piety empowering charismatic true believers. Holy Trinity Brompton led the way - a parish serving as a global spiritual refueling station. But it was always about more than the piety. Along with inviting people to get baptized in the Spirit, Holy Trinity heavily promoted the Alpha Course, a packaged and orderly presentation of what they consider basic Christianity, but is, in reality, a kind of systematic evangelical vision of the Bible and what could be called “soft” hierarchy. While Alpha has reached millions of people around the globe, there’s been a consistent line of criticism around it as well, mostly from those suspicious that Alpha promotes a quietly traditionalist political agenda.

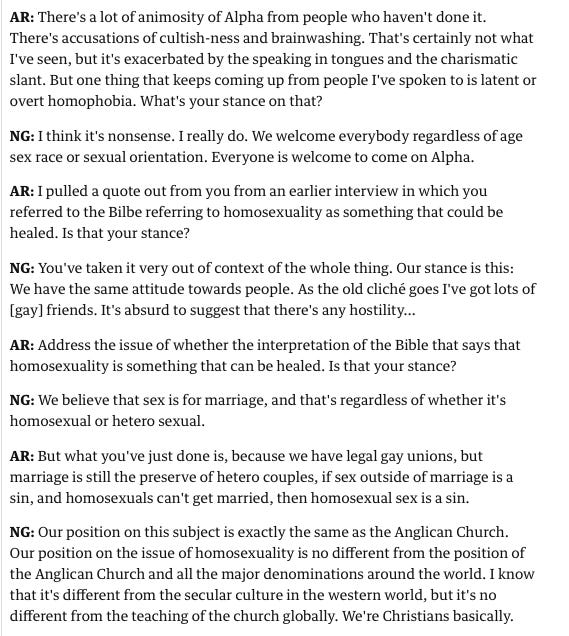

Here’s part of an interview with Holy Trinity’s rector Nicky Gumble from The Guardian in 2009:

And more along the same lines, with increasing frustration on the part of the journalist:

If you read the entire interview, you’ll notice there is a thread throughout: a particular form of Christianity based on submission to authority dominates and a certain style of genial non-answers is the vicar’s stance. The interview clearly reveals a theology of insiders and outsiders while - at the very same time - presenting certainty and their desire to convert the world with a kind of “aw shucks, I’m just a regular guy who like every other regular Christian” persona. Reporters have long noticed Gumbel’s practice of side-stepping:

Nicky is on stage, leaning against the podium, smiling hesitantly. He reminds me of Tony Blair. "A very warm welcome to you all. Now some of you may be thinking, 'Help! What have I got myself into?'" A laugh. "Don't worry," he says. "We're not going to pressurise you into doing anything. Perhaps some of you are sitting there sneering. If you are, please don't think that I'm looking down at you. I spent half my life as an atheist. I used to go to talks like this and I would sneer."

Nicky is being disingenuous.

The article is titled, “Catch Me If You Can.” The stealthy bit again.

The charisma is there - and one part of the agenda is perfectly clear: join the church. Indeed, another reporter who attended Alpha discovered that the final week was intended to recruit her to a local church. When she asked the leader, “Why should I join?” He replied, “because if you’re a Christian, you’re our friend.”

Be like us. Join up. The soft-sell business guy. The “I’m just like you” wink-wink. That disarming way that Nicky Gumbel is, indeed, going to “pressurise” you and take you somewhere you ultimately don’t want to go. Whether a business suit or a clergy collar, there’s something else here - an agenda behind the smile. Come to Alpha. Join up with us. You’ll be our friend. Only, however, if you are a Christian. And, most likely, only a certain kind of Christian at that.

“Nicky is being disingenuous.” Those words trouble this Virginian. Glenn Youngkin went to his church just then - at the time of these articles - in the first decade of the twenty-first century, a few years after my visit to London. Nicky Gumbel was Glenn Youngkin’s pastor. Maybe his role model, too. The business suit, the clergy collar - in this Virginia election, it has become a fleece vest.

Be our friend. The line might echo the words of Fred Rogers, the radically inclusive Presbyterian minster and television host, but it hints of something else. Something conditional, something secretive - if you’re a Christian. If you agree with us, if we believe the same things.

We’re a long way from Mr. Rogers here.

* * * * *

The front page of Holy Trinity Church in McLean, Virginia states:

HTC is a Christ-centered, non-denominational church with Anglican roots and a contemporary charismatic expression.

Anglican roots. Charismatic expression. “Holy Trinity” just like Holy Trinity Brompton.

Holy Trinity Church in McLean was founded by Glenn Youngkin. In his basement. This pull quote from the AP sounds a vaguely familiar homage to his years in London:

It is worth noting that Youngkin’s foundation owns the building in which HTC is housed. The church pays him $1 for its yearly rent. And Youngkin served on its vestry (Anglican term for “church board”) for years. On the church’s tenth anniversary (last October), Glenn Youngkin and his wife gave their “Top Ten” reasons why they loved HTC on a Facebook video - reason #2 being “Alpha” and reason #1 being “The Holy Spirit.” (Don’t be surprised if they take down or limit views to the video if this column gets any traction).

Over the decade, the church’s clergy have mostly been Anglicans - having connections with Holy Trinity Brompton and the charismatic Episcopal churches in Fairfax County (none of which are still part of the Episcopal Church - all of which left the denomination over LGBT ordination). But this year that changed and the two lead clergy now come from Pat Robertson’s Regent University’s theological training program - no real Anglican connections there, but with more obvious Pentecostal and religious right ties.

After I tweeted about this, a follower reached out to me by email:

“Saw your tweets on HTC, the Youngkin church. We’ve gone a few times. It feels very evangelical and not overtly partisan. For instance, big push to help Afghan refugees right now. But the last time we were there, maybe 6 weeks ago, left the sanctuary and went into the lobby and Josh Hawley was out there shaking hands. Had a visceral reaction. Never went back.”

My correspondent, who liked the church (and praised its diversity), further said: “Something about the church and Youngkin and the Republican politics in the background felt creepy to us.”

I remember walking out of Holy Trinity Brompton all those years ago - I didn’t know what to say. It wasn’t really the Pentecostal worship. Something in the background felt, well, creepy.

* * * * *

So what does this say about Glenn Youngkin?

It tells me that he isn’t being straightforward about his connections, his intentions, and his political agenda. Youngkin is shaped by a religion that, over the decades, has slowly and surely given its soul to Trump Republicanism, revealing it worst motives of inequality, racism, and authoritarian order. But Youngkin also learned to cloak whatever may be off-putting or seem extreme regarding his faith in regard to politics. He knows how to speak to the secular world and how to use power. The fleece, the smile, the genteel “Anglican roots,” all serve to smooth over an exclusivist and literalist faith, right-wing political activism, and its theo-political quest for the Kingdom of God on earth. It is Christian nationalism with a human face, and carrying a prayer book to boot. All designed to comfort and reassure suburban Virginians that all will be well, especially when the patriarchs regain control.

And it reminds me that I’ve heard someone warn of this before. Oh yes. Jesus.

“Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing but inwardly are ravenous wolves.” (Matthew 7:15)

Do fleeces count as sheep’s clothing?

INSPIRATION

Lying is an occupation,

Used by all who mean to rise;

Politicians owe their station,

But to well concerted lies.

These to lovers give assistance,

To ensnare the fair-one's heart;

And the virgin's best resistance

Yields to this commanding art.

Study this superior science,

Would you rise in Church or State;

Bid to Truth a bold defiance,

'Tis the practice of the great.

— Laetitia Pilkington, c. 1740

Pretty much any Episcopalian who has been around northern Virginia for a while will tell you that these congregations are NOT benign - that they are deeply politicized and political communities committed to anti-democratic ideals and principles. And that they foster division under the guise of ideals like "renewal," "love," and "unity."

For those of you who are attuned with such things, HTC McLean's mission statement is LOADED with Dominionist/Reconstructionist language - "truth and power of the Word," "Sovereignty" (not a typical word used in Anglican church ads!), "Lordship" (in a particularly Pentecostal kind of way), the "Mission" (capital "M"). https://www.htc.us/what-we-believe