Discover more from The Cottage

Warning: This post contains mentions of religion and sexual abuse.

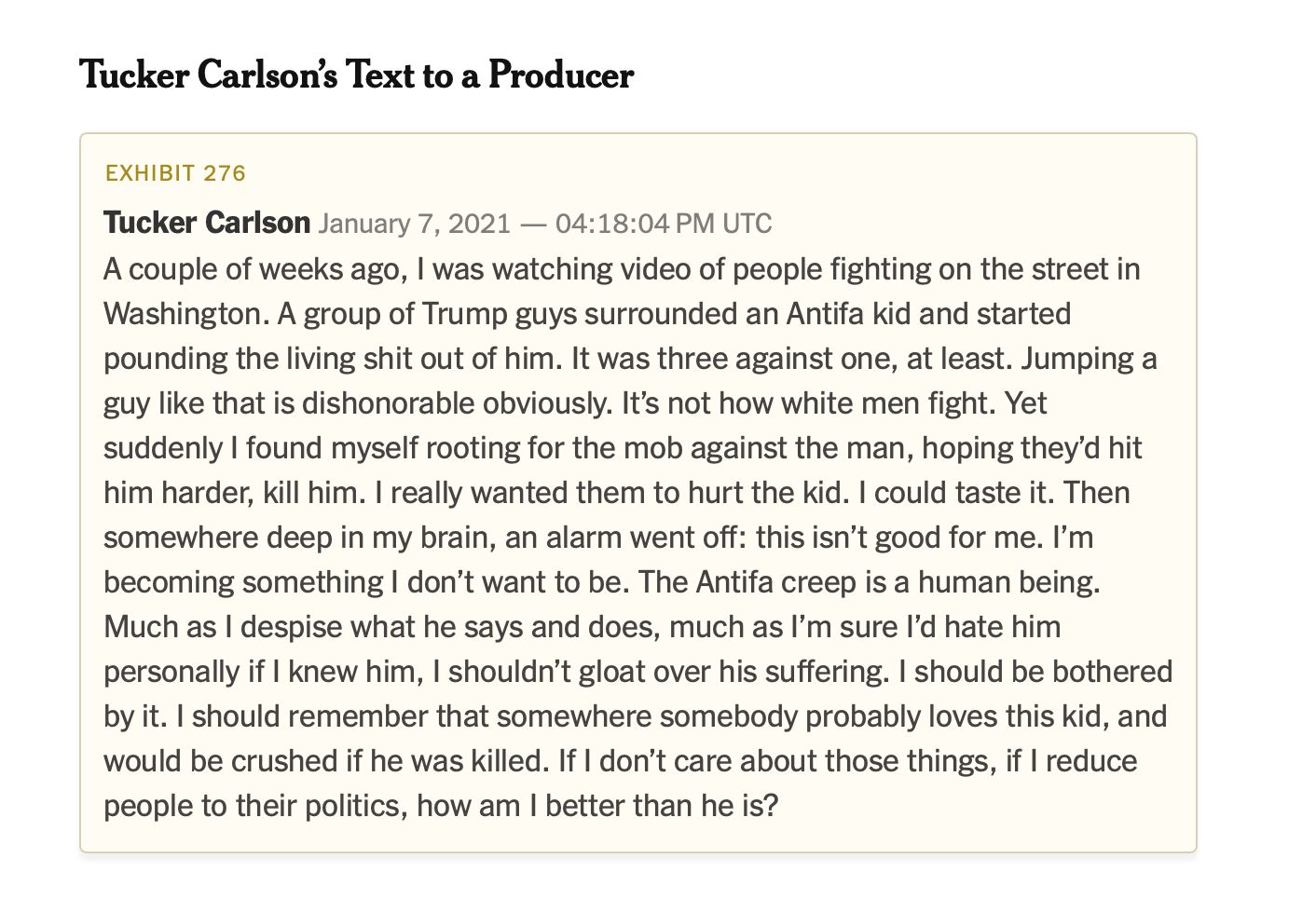

This week, the New York Times reported that Tucker Carlson may have been fired from FOX News for comments about race discovered among his texts in the Dominion lawsuit. The messages are disturbing — especially this one, “It’s not how white men fight.”

These racially charged comments, combined with the allegations against Carlson brought by Abby Grossberg, a former FOX News producer, of sexual discrimination and gender bias by him and his staff, surely contributed to the downfall of the most powerful right-wing broadcaster in American politics.

On the face of it, religion doesn’t seem to have much to do with this story. But, in recent years, Carlson has attacked social justice Christians, Black Christians, and liberal members of his own denomination — the Episcopal Church.

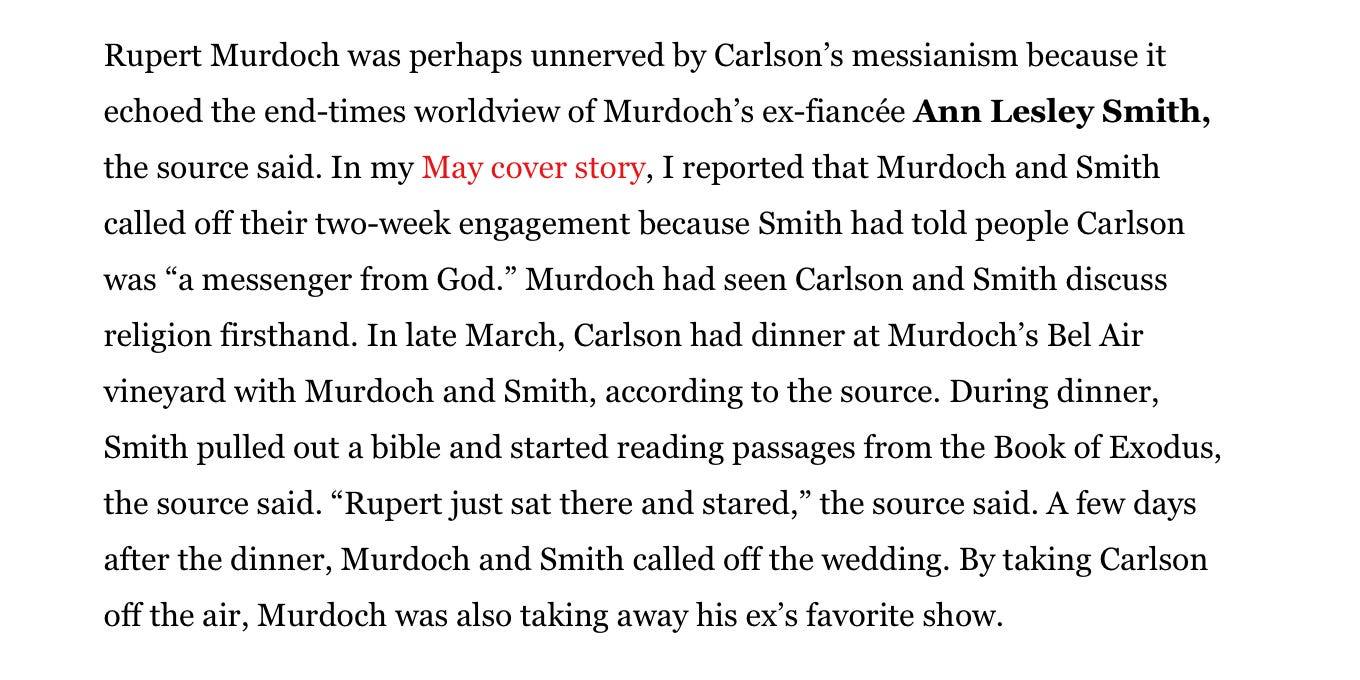

Vanity Fair was the only major publication to suggest that religion may have played a role in his firing. In a recent speech to the Heritage Foundation, Carlson described the world as locked in a religious battle between good and evil. Rupert Murdoch, FOX chair and founder, is (at least) vaguely hostile to religion. But not his ex-fiancee. She was a major fan of Carlson, calling him a “messenger of God.” Vanity Fair reports that this may have contributed to Murdoch’s sudden booting of his star:

That’s some romance revenge.

All this raises questions about Carlson’s religious views — ideas he increasingly puts center-stage. Here’s the key section from the Heritage Foundation speech that angered Murdoch (from a viral post on Twitter — click on it to listen):

While the entire clip is troubling, Carlson’s ridicule of the Episcopal Church is striking. It isn’t the first time he’s called his own church “shallow” and remarking, “it’s not even a Christian religion at this point, I say with shame.”

Why remain a member of a church you hate? A church you are ashamed of?

Carlson’s relationship with the Episcopal Church has often been noted in the press:

His roots in Anglicanism run very deep. He is a cradle Episcopalian from California who went to St. George’s School in Rhode Island. There he met his future wife, who is the daughter of Fr. George Andrews, the former headmaster.

His divorced parents raised him (at least loosely) in the Episcopal Church. In 1983, when he was 14, Carlson was sent to St. George’s, an elite private school, one of the educational crown jewels of the denomination.

A year later, in 1984, the Reverend George Andrews arrived to be the school’s new headmaster — and his daughter, Susan, would eventually date and later marry Tucker Carlson. And thus, Tucker Carlson’s father-in-law is an Episcopal priest, one who once held a plum appointment at a posh boarding school.

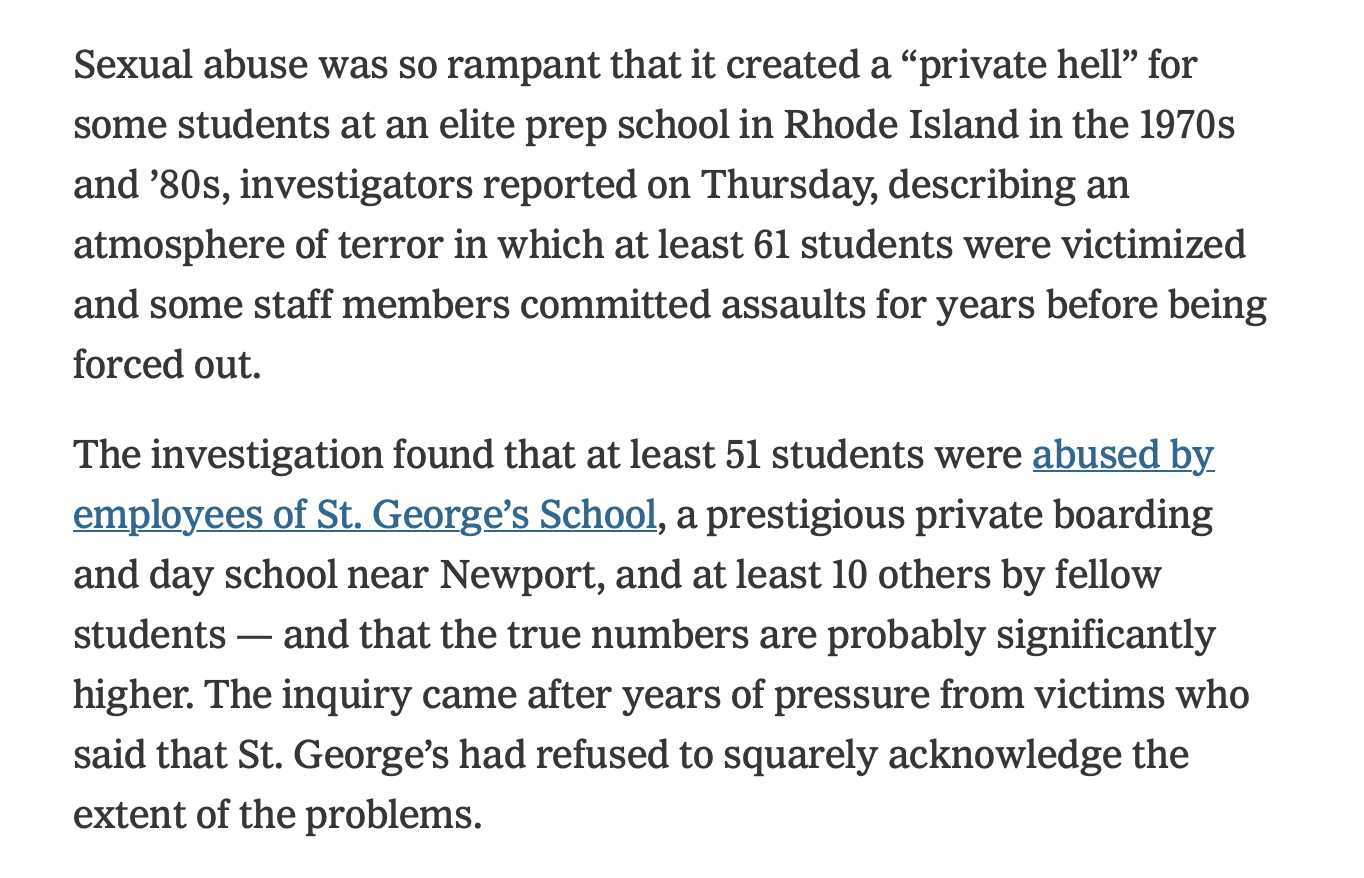

While most articles mentioning Carlson’s education praise St. George’s elite status, they fail to mention the fact that the school was also the site of the worst sexual abuse scandal in the modern Episcopal Church. Here’s the lede from the New York Times story, “‘Private Hell’: Prep School Sex Abuse Inquiry Paints Grim Picture,” from September 1, 2016:

The results of the inquiry — the entire 400 page report — are posted online. Investigators were charged to answer the question of how this happened and examined “in detail what the school’s leaders during those years did—or failed to do—to protect students from abuse.”

The most relevant question is whether school leaders took the steps necessary to prevent, to the extent possible, teachers or staff from molesting students, or to prevent older students from sexually assaulting younger students. Our investigation reveals that, in the 1970s and 1980s, St. George’s leaders did little, and certainly not enough.

To be clear, we do not find that St. George’s leaders did nothing; in fact, they certainly took some concrete steps to protect students. . .

But the school made no contemporaneous report to any law enforcement authorities about [the teachers] despite having information making it clear they committed sexual abuse against students.

George Andrews was the headmaster from 1984-1988, nearly the exact years in which Carlson was a student, and during which a music teacher was accused of abuse by a number of victims.

After almost a decade at the school, that teacher was terminated. The report covers Andrews’ account of the events in some detail. There is no suggestion that Carlson’s father-in-law was in any way involved in abuse. The investigation was about how he handled it and what he knew at the time. No charges were brought against him and the report indicates that he attempted to do some things — but he did not inform police authorities about the abuse (there seems to be genuine uncertainty as to whether St. George’s case fell under the governing laws of Rhode Island for reporting sexual abuse of minors.)

A year after the teacher was fired, however, the Rev. Andrews was informed that his contract would not be renewed. He moved to Florida where he subsequently served as the headmaster of an Episcopal school (1989-2007) and established a consulting service for hiring chaplains at private schools.

Following the revelations of the St. George’s scandal, the Diocese of Southeast Florida opened an investigation into Andrews as well (the story was reported by a FOX News affiliate in Florida). There is no indiction how this investigation and any legal issues it raised were finally resolved. However, the investigation must have satisfactorily cleared Andrews because his consulting service still exists.

Episcopal Church officials are unwilling to talk about St. George’s, most likely due to legal reasons, settlements, and not wanting to draw further attention to this painful episode. The only public conclusion of the story was the release of the 2016 report detailing abuse at the school.

The report, which admits to and apologizes for horrifying episodes, includes this explanatory codicil among its findings:

We do not conclude that St. George’s leaders during the 1970s and 1980s acted differently than the leaders of many other boarding schools in New England or elsewhere in the United States. Nor do we find that the school’s leaders intended that students be abused, or consciously wished their students to suffer. The features of school life at St. George’s that paved the way for abuse of students by faculty and staff, and for sexualized hazing and sexual assaults of younger students, were common features of boarding school life in those times. Rules permitting faculty to take students on overnight or weekend trips, sometimes at the school’s expense; absent dorm parents who let older students run dorms where younger boys and girls lived—these were by no means unique to St. George’s.

But the fact remains that it was St. George’s that employed White, Gibbs, Coleman [the main abusers] and others; failed to recognize or act on information suggesting Gibbs was failing to respect appropriate boundaries with female students; chose to award Gibbs grants for distinguished service until his death; chose to continue to employ Coleman after serious concerns about his conduct were raised; continued to recommend Coleman for other jobs even after his dismissal; and created an environment where few students felt as if they could report abuse they experienced or knew about. [Emphasis mine]

Our conclusion, in the end, is this: in the 1970s and 1980s, St. George’s School betrayed the trust of the many St. George’s students who became the targets of sexual abuse when they came to the school . . .

That’s quite a sentence: “The features of school life at St. George’s that paved the way for abuse of students by faculty and staff, and for sexualized hazing and sexual assaults of younger students, were common features of boarding school life in those times.”

I guess New England prep school boys were just boys — even when they were faculty members — in those days.

* * * * *

What of Tucker Carlson, who was a student at the school from 1983 to 1987 while these events unfolded — and eventually became the son-in-law of the headmaster whose life was forever altered by them?

As I write this, I want to make it perfectly clear that I do not believe nor want to suggest (or even imply) that Carlson was either a victim or perpetrator while at St. George’s. Everything in today’s post is a matter of public record, easily accessible on the internet, and this is all information — nothing of accusation. There is no indication that Carlson was anything other than a New England prep school student who happened to fall in love with the daughter of the headmaster who wound up in the center of this case.

However, knowing this history may clear up one question while it raises another one.

First, these events may answer the question of why Carlson is angry at the Episcopal Church. The 2015 revelations about St. George’s and subsequent investigations must have had a profound impact on the Carlson family and their faith.

It isn’t hard to imagine how shocking it must have been to have one’s father-in-law involved in the very public reckoning of sexual abuse cases from thirty years previous. Since no one from the Episcopal Church will talk about it, it also isn’t hard to imagine that there were some pretty significant — and unpleasant — conversations internally between the priest-headmaster and authorities in that denomination.

Carlson displayed animus regarding the Episcopal Church before 2015. As a conservative in a liberal denomination, he wasn’t happy when the church consecrated a gay bishop. In this 2013 interview, a right-wing magazine asked why he went to the Episcopal Church. Carlson replied: “I’m a shallow guy! That’s why I still go to the Episcopal Church. But I like it! I just don’t want to think too hard about my money going to these pompous, blowhard, pagan creeps who run the church!”

But his criticism intensified during the years of the St. George’s scandal. Carlson seemed increasingly aggrieved (not humorously so) with the Episcopal Church — something occasionally commented upon by observers on social media. By 2018 and 2019, he was theologically cozying up to Christian nationalists, even more than in the past. His anger seemed to reach a boiling point in this month’s Heritage Foundation speech, leading some pundits to wonder if Carlson was about to quit the Episcopal Church and perhaps become a Catholic.

Did the St. George’s scandal add to Carlson’s dissatisfaction with his own church? I can’t help but wonder if family dynamics and internal institutional pressures contributed to his anger against the Episcopal Church. It would be easy to be mad at a denomination investigating one’s father-in-law under such ugly circumstances. Perhaps it is better to blame an institution rather than a believe a relative could be involved in these terrible events.

Second, even as this might provide some insight into Carlson’s displeasure regarding with his denomination, it raises an important question about the impact of sexual abuse in religious communities.

One needn’t be a victim, perpetrator, or a knowledgeable bystander to understand that sexual abuse on this scale happens in toxic environments where people keep secrets.

In recent years, many religious organizations have faced disclosures about sexual abuse — the most notable being those in the Catholic Church and the Southern Baptist Convention. There have been tragic revelations, a few apologies, some reparations, and attempts at institutional repair.

But there’s been little talk about how being formed — as a human being and as a Christian — in a toxic, abuse-ridden church or school impacts everyone in such an organization, even those with no first-hand knowledge of any specific events.

The abuse at St. George’s involved more than 60 victims, a half-dozen teachers, and a few administrators. That’s not an insignificant number in an insular private school community. However, it isn’t the just the specific victims. It is equally true that everyone breathed the dank moldy air of these misdeeds. Even those blissfully unaware of this behavior lived in this toxic culture — a culture described in the St. George’s report as being “common features of boarding school life in those times.” Sexual abuse seems private, but it is really a violation against a community.

The report points out that what happened at St. George’s wasn’t just about 60 victims and a handful of teachers. Instead, it was about an environment: “This report also tells the story of a culture of hazing and bullying, absent adults, and disrespect, particularly of girls and young women, that together created an environment that permitted older students to commit assaults, including sexual assaults, against younger students—girls and boys.”

Toxic cultures create other toxic cultures. Indeed, those raised in abusive environments are at high risk to become abusers. Everyone is scarred in some way or another, to a greater or lesser degree, as if spiritually imprinted by the secrets around them.

Abby Grossberg, who is currently suing FOX News, alleged that Carlson’s team "subjugates women based on vile sexist stereotypes, typecasts religious minorities and belittles their traditions, and demonstrates little to no regard for those suffering from mental illness." While still employed by FOX, Grossberg complained about abuse at his show:

"I ultimately went and complained to one of my supervisors about the abuse and the bullying and the gaslighting and misogyny that I was putting up with at Tucker," Grossberg said. "And his response to me was, 'We're just following Tucker's tone. That's Tucker's tone.' And I do really believe that it all trickles down from the top."

Indeed, this comment sounds like the complaints of people mistreated in abusive environments. And her accusations sound painfully like the kind of vulgarity and misogyny that might exist in a fraternity — or a New England prep school in the 1970s and 1980s?

Of course, not everyone who attends a church or school where abuse was present winds up replicating toxicity or abuse (of differing kinds and degrees). But some do. Secrets have consequences, effecting many people beyond the immediate circle of abuse, showing up in unlikely places in unexpected ways. Being a teenager in a poisoned environment, especially one where abuse hides under the guise of religion, can be a very hard legacy to shake.

Is this an aspect of what we are seeing in the fall of Tucker Carlson? The dim reflection of a New England prep school in a FOX News studio? A New England prep school with a secretive and abusive religious culture, a “culture of hazing and bullying, absent adults, and disrespect, particularly of girls and young women”?

Maybe? Just maybe.

* * * * *

I don’t think that religion is an excuse or an all-encompassing explanation. I’ve no idea what led Rupert Murdoch to fire Tucker Carlson. There’s no way to predict how Grossberg’s case will be resolved and whether we will ever know the truth about her allegations. Anyone who says they know is speculating at this point.

But the story of St. George’s adds a dimension of understanding to Carlson’s career and fall — making us wonder about the impact of being a student at a school run by a religious institution while a hellish culture of abuse grew largely unchecked.

Are those events of the 1980s — and their revelation in 2015 — part of this larger story? Does this lend insight to the case of Tucker Carlson? I imagine so, just by weaving together the pieces of this sad story scattered across publications through the years. There’s no “smoking gun” having anything to do with Carlson, only the fact that he was student at a school where terrible things happened — and that, through marriage, these events continued to impact his family even recently. It is an odd religion slant into a big news story about the downfall of a major media figure.

Thinking about St. George’s, I’m angry for the victims. But, strangely enough, in recounting it, I find myself seeing Carlson as more human, a person schooled by miscreant adults in whose care he had been placed.

I didn’t want to wind up with empathy for him — for I’ve never liked Carlson and despise the pain he’s caused to many millions through his show. However, the victims — and all the school’s students, including Tucker Carlson — deserved better than what they got.

I doubt he’d appreciate my sympathy — wondering about how a young boy might be wounded by such an environment. I suspect he’d attack me as a bleeding-heart Episcopal liberal with “shallow” theology and a penchant for therapeutic explanations. But I find myself with questions — I’d like to hear his honest experience about these things — and how St. George’s history mattered to his life and his choices. Carlson’s Episcopal story raises lots of questions, none of them amusing, and many laden with sad possibilities.

Ultimately, this is about more than Tucker Carlson. Looking at the religion piece of this story, we are left wondering: What about all the people raised in Catholic churches where abuse occurred, all the Baptists in congregations were abusers victimized children? We think of the victims, yes. But we should also think about the next circle — those on the edges who absorbed — often without knowing — the toxic culture in which they lived, worshiped, and learned. What happened to them? What of their healing — or not?

How does sexual abuse in religious institutions affect us all? We don’t entirely know. But the tentacles of such evil seem long, entangled in more than we imagine.

For some reason, I hear Jesus’ words inwardly: For nothing is hidden that will not be disclosed, nor is anything secret that will not become known and come to light. It feels less a threat than a comfort — such transparency may be our only salvation. I would hope that Tucker Carlson and I might agree on at least that.

These remarks in the report are important to note:

“Facts are stubborn things,” as John Adams said nearly 250 years ago, and they must be reckoned with. The picture that emerges from this investigation is profoundly disturbing. . .

I am also mindful that our world has changed dramatically since the 1970s. I have sought to resist the temptation to make assessments about yesterday’s leaders by today’s standards. But it would be wrong, in my judgment, to turn a blind eye to what happened decades ago merely because the world was different then, or because St. George’s School today is a very different place than it was in the 1970s and 1980s.

INSPIRATION

spiders of misogyny

by Tasha, as posted by Pádraig Ó Tuama on his website

when I call you out on the third rape joke this week, you moan

you moan to me about how it is only a bit of fun

about how it is so outrageous that I should know you don't mean it

you moan that I am not letting you be one of the guys

when I ask you to stop being sexist and making comments about getting back in the kitchen

when I tell you the statistics you say "but what about the men?"

when I tell you about the men in a van who called out to me on the street with leering eyes you say "isn't that a compliment" . . . .

READ THE ENTIRE POEM HERE

This May, we celebrate the third birthday of The Cottage! THANK YOU for being part of this adventure of faith and words.

The statement that St. George's was not unlike other private boarding schools in the 80's is undoubtedly a factual statement. But it is an understandable, yet problematic attempt to avoid real repentance, in my opinion. Having been the director of the rape crisis center located near Penn State during the Sandusky scandal, I know that while "every place was like that" may be factual it is not helpful nor relevant when talking about any particular institution's responsibility to victims. As you so thoughtfully point out, it is also problematic as we try to understand the damage to all those who have been shaped by a toxic environment. The issue isn't that "it was like that everywhere" the issue is "this is who we were, what we allowed to happen, what we owe the victims, and what must be done so that this never happens again." Full stop. I also think that you are absolutely right that the issue is broader than a few bad actors. To truly address the issue of sexual abuse in institutions, any institution, one must look at not just individual actors, but at the institutional culture and what supports and sustains it and the way it shapes those who were not themselves victims or perpetrators. Because it does. And this is what is so often missed in conversations about abuse in institutional settings. It is also, I believe, why there is often push-back against needed reforms. Those who weren't perpetrators or victims don't see the connections, and so resist changes to the environment. They literally don't realize that the air was poisoned because they aren't the ones who got sick. Repentance and repair are and must be multi-layered. Thank you for this insightful post and the poem which illustrates the point so well.

Diane, I'm sure this article was as difficult for you to write as it was for me to read! WE cannot continue to turn a blind-eye to evil.