Discover more from The Cottage

Last week, Virginia governor Glenn Youngkin’s Department of Education issued a draft of its new Social Studies and History standards for public schools. The response from teachers and professional historians was swift and critical.

James J. Fedderman, president of the Virginia Education Association, issued this statement:

The standards are full of overt political bias, outdated language to describe enslaved people and American Indians, highly subjective framing of American moralism and conservative ideals, coded racist overtures throughout, requirements for teachers to present histories of discrimination and racism as ‘balanced’ ‘without personal or political bias,’ and restrictions on allowance of ‘teacher-created curriculum,’ which is allowed in all other subject areas.

His points are well taken, and it is clearly an attempt to “whitewash” history to support Youngkin’s main election promise — to eliminate “critical race theory” from Virginia schools.

It is also important to note there are rumors flying around social media about the standards. Most significantly, Martin Luther King, Jr. has not been eliminated from the history curriculum. Kindergarteners are specifically instructed to learn about two important holidays — Presidents Day and Martin Luther King Day. King’s legacy is covered in sixth grade and in high school in two (relatively substantial) units on the Civil Rights Movement.

(SIDENOTE: The Department of Education issued a “revised” version after a storm of criticism; the first version released last Friday had, as officials claim, “inadvertently” omitted King Day and Juneteenth in elementary levels.)

It is important to identify what the problems are — and get the central issues right. Teaching history is central to a nation’s sense of identity and its practice of politics. How we understand the past informs the decisions we make about the present and shape our dreams for the future.

There’s no doubt that the current draft minimizes diversity, especially the contributions of brown and Black Virginians, as well as Asian-Americans, LGBT persons, and other marginalized people. Yet, the draft standards represent a fairly conventional — if slightly modified — view of Eurocentric history, along with unfettered praise of conservative economic and political ideals. Basically, the curriculum echoes American history as taught in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

With the conflicts over the teaching of American history now, it seems the new standards could have been even worse. As far as I could tell after closely reading the draft, the document promoted no overt Christian nationalism, no clear insistence on American exceptionalism or manifest destiny, no dependence on Donald Trump’s abysmal “1776 Project,” and plenty of opportunities for good teachers to introduce material to balance views on genuinely controversial historical theses.

But focusing on what has been left out isn’t the only concerning aspect of the standards. I’m worried about what the revisionists put in.

The writers added something ignored by even the most vocal critics. The second grade standards used to be an overall introduction to major figures in American history. The new draft cut the American history section in half to add a substantial unit on Egypt, making ancient Egypt the first civilization young students will study other than their own.

Why would that be a problem? It seems a good thing to introduce second graders to a bigger vision of the world.

Read the section on Egypt from the draft:

Students will apply history and social science skills to describe the geographical, political, economic, social structures, and innovations of Ancient Egyptian Civilization by:

describing daily life in Ancient Egypt (e.g., the importance of the Nile River, farming, hieroglyphics, polytheistic religion, art);

explaining why Egyptians thought that the Pharaohs were both divine and mortal, “God Kings”;

describing the importance of mummification, pyramids, the Sphinx, and belief in an afterlife; and

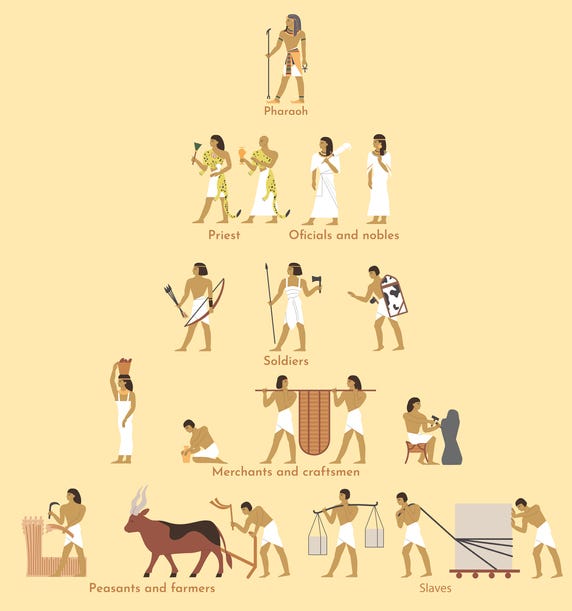

explaining the social class system of Ancient Egypt, including its enslaved people.

Mummies, of course, are cool. Learning about Africa is important. And who doesn’t like a classroom decorated with pictures of pyramids and sphinxes?

But it isn’t just about fun history. Teaching second graders about ancient Egypt is their first lesson in social structure — how communities should be shaped, who has power and who doesn’t, where wealth resides and who has status.

One of the most significant intellectual tasks for second graders is developing new connections — things like cause and effect, looking for similarities and differences, and tying together basic ideas and stories. Second graders like beginnings, middles, and ends. They like to draw lines from point A to point B and beyond.

Ancient Egypt is interesting, and a subject worthy of historical attention in every way. But putting it first? And pairing it with American history?

The implication, in the mind of a second grader at least, seems pretty clear. Whatever happened in ancient Egypt leads to what eventually happens in Virginia. There’s some sort of cause-and-effect at work here.

Basically, Virginia seven-year olds will not only be learning about pyramids (neat!) but about a pyramid-shaped society — complete with ideas of the divine right of rulers, a religion-infused culture obsessed with life after death, and a social structure based on slavery. You don’t need to be a second grader to draw connections between ancient Egypt and nineteenth-century Virginia.

Our social imaginations develop early. Stories teach us about the structure of the world. When I was in elementary school, the first social structure we studied was that of Egypt — a pyramid-shaped society.

But it wasn’t the last. Egypt was followed by ancient Greece and Rome, both of which were highly structured patriarchal social pyramids. When those pyramids collapsed at the fall of Rome, we learned that Europe plunged into a Dark Age (not true, of course), a descent only halted when Christianity’s Great Chain of Being created a new feudal order and saved civilization.

We were taught that movements like the Renaissance and the Reformation — and later, the Enlightenment — corrected some of the worst pyramidal abuses (like the problem of immoral popes or kings). But European history was generally told as the story of a well-ordered social pyramid where the “right” people are rewarded with wealth and power, and those of lesser status accepted their lot.

For generations and well beyond Virginia, American children have been, in effect, taught that social pyramids — with their attendant hierarchies — are normal and normative. If Egypt comes first, the lesson is clear: the pyramid is the most ancient form of human organization, the most successful form of civilization. The details may change through the centuries, but the basic form remains.

In the new standards, there’s little indication of an alternative. There’s no mention of a social structure where pyramids are minimized, where hierarchies aren’t divinely ordained. But human history is full of non-pyramid societies — tribal societies (indeed, tribal societies were removed from the Virginia standards), communities organized around sharing, federations, and cooperation, and politics based on principles of mutualism and visions of common good.

Without an alternative historical story, imagining a different social structure is difficult, if not nearly impossible. Indeed, the worst human political systems — and the greatest tensions and temptations in contemporary politics — authoritarianism, fascism, theocracy, Christian nationalism, systems of ethnic superiority, and oligarchies, all depend on strict hierarchies and rigid pyramids of gender, class, and race.

People do protest pyramids. Western history is replete with rebellions against hierarchies. But our language, our story-universe, and our vision are less clear when it comes to offering alternatives to pyramids. We might speak of “democracy” or “equality” in vague terms, social justice, or the “beloved community,” but the truth of the matter is that we aren’t introduced to a wide range of possibilities as schoolchildren. We lack the narrative skills to invite people into a more dynamic, diverse, and less top-down future. Our social imaginations have been largely inhibited, perhaps even purposefully aborted, and creative possibilities for politics and change stymied.

A people can’t work toward what they can’t imagine.

And that’s the real danger of the Virginia standards. The closing of the American imagination. The Youngkin curriculum reifies, re-centers, and glorifies the pyramid of power that has oppressed so many for so long.

We need to see history differently if we are to create a better future.

INSPIRATION

There is a wave of gratefulness because people are becoming aware how important this is and how this can change our world. It can change our world in immensely important ways, because if you're grateful, you're not fearful, and if you're not fearful, you're not violent. If you're grateful, you act out of a sense of enough and not of a sense of scarcity, and you are willing to share. If you are grateful, you are enjoying the differences between people, and you are respectful to everybody, and that changes this power pyramid under which we live.

― David Steindl-Rast

Collaboration has no hierarchy. The Sun collaborates with soil to bring flowers on the earth.

― Amit Ray

All the elders of Israel gathered together and came to Samuel at Ramah. They said to him, “You are old, and your sons do not follow your ways; now appoint a king to lead us, such as all the other nations have.”

. . . Samuel told all the words of the Lord to the people who were asking him for a king. He said, “This is what the king who will reign over you will claim as his rights: He will take your sons and make them serve with his chariots and horses, and they will run in front of his chariots. Some he will assign to be commandersof thousands and commanders of fifties, and others to plow his ground and reap his harvest, and still others to make weapons of war and equipment for his chariots. He will take your daughters to be perfumers and cooks and bakers. He will take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive groves and give them to his attendants. He will take a tenth of your grain and of your vintage and give it to his officials and attendants. Your male and female servants and the best of your cattle and donkeys he will take for his own use. He will take a tenth of your flocks, and you yourselves will become his slaves. When that day comes, you will cry out for relief from the king you have chosen, but the Lord will not answer you in that day.”

But the people refused to listen to Samuel. “No!” they said. “We want a king over us. Then we will be like all the other nations, with a king to lead us and to go out before us and fight our battles.”

When Samuel heard all that the people said, he repeated it before the Lord. The Lord answered, “Listen to them and give them a king.”

— from 1 Samuel, chapter 8

A poem, “Pyramids” by Richard Moore.

GEORGIA ON OUR MINDS

SOUTHERN LIGHTS 2023 is back! Y’all come!

This coming January on St. Simons Island in Georgia, Brian McLaren and I are hosting extraordinary guests including Irish poet Pádraig Ó Tuama, theologian Reggie Williams, and Franciscan sister and scientist Ilia Delio in a weekend festival of reimagining faith in words, for the world, and in context of the cosmos — poetry, theology, and science!

We’re also going to do live, on-stage podcasts with guest pod hosts Grace Ji-Sun Kimand Tripp Fuller — and great music from the wonderful Ken Medema.

Please join us in Georgia or virtually online. CLICK HERE for info and registration!

SEATS ARE SELLING FAST!

In a certain sense, the story of the Bible is the Israelites first escaping Egypt and then trying to avoid *becoming* Egypt. But the story still essentially starts there.

Does the curriculum have any suggestions for framing? I can imagine a creative teacher assigning projects that help students see ancient Egypt through the perspective of a worker or slave as opposed to a Pharaoh or priest.

these are such important thoughts, this post and a recent you posted focused on table vs hierarchy. I have thought about that a lot and deeply. I am a life-long church goer and have of late been part of an ecumenical group composed of Christians, Jews, Atheists, Bhuddists, Unitarians. It is a small group and we choose amoungst different questions, those "big" type questions and then put forward our ideas on them. I am finding so much room for growth, for exploration, for gentle listening without preaching at me, appreciation, there is little defensiveness. It is a table (metaphorical), it is not in any way hierarchical. There is so much I have learned. But I want to say this, the posts I find here, without fail, inform this same learning and exploration. I want to thank you for that. While it is the case your theological studies are more formal than mine, I always sense an approach that has a foundation of equality and respect. This is very much appreciated.