Discover more from The Cottage

Religion News Service was quick to point out that Kamala Harris, the newly selected Democratic vice-presidential candidate, is both bi-racial and bi-religious:

Harris, who was born in Oakland, California, to a Jamaican immigrant father…and an Indian immigrant mother…is both Black and South Asian. She grew up in a home that accommodated both Christian and Hindu religious practices.

Black and Asian. Christian and Hindu.

Over the coming weeks, it is important to remember the “and” of Kamala Harris’ experience. That little word – and – is a conjunction which, as the dictionary puts it, connects things “that are to be taken jointly.”

We forget how important “and” is, this small, modest word. In the case of Sen. Harris, the “and” acts as a bridge between identities that most people consider distinct. Race and ethnicity, faith and religion – these are humanity’s unbridgeable divides. When we imagine these things, we picture boundaries, borders, and walls. Not unity, not what we share.

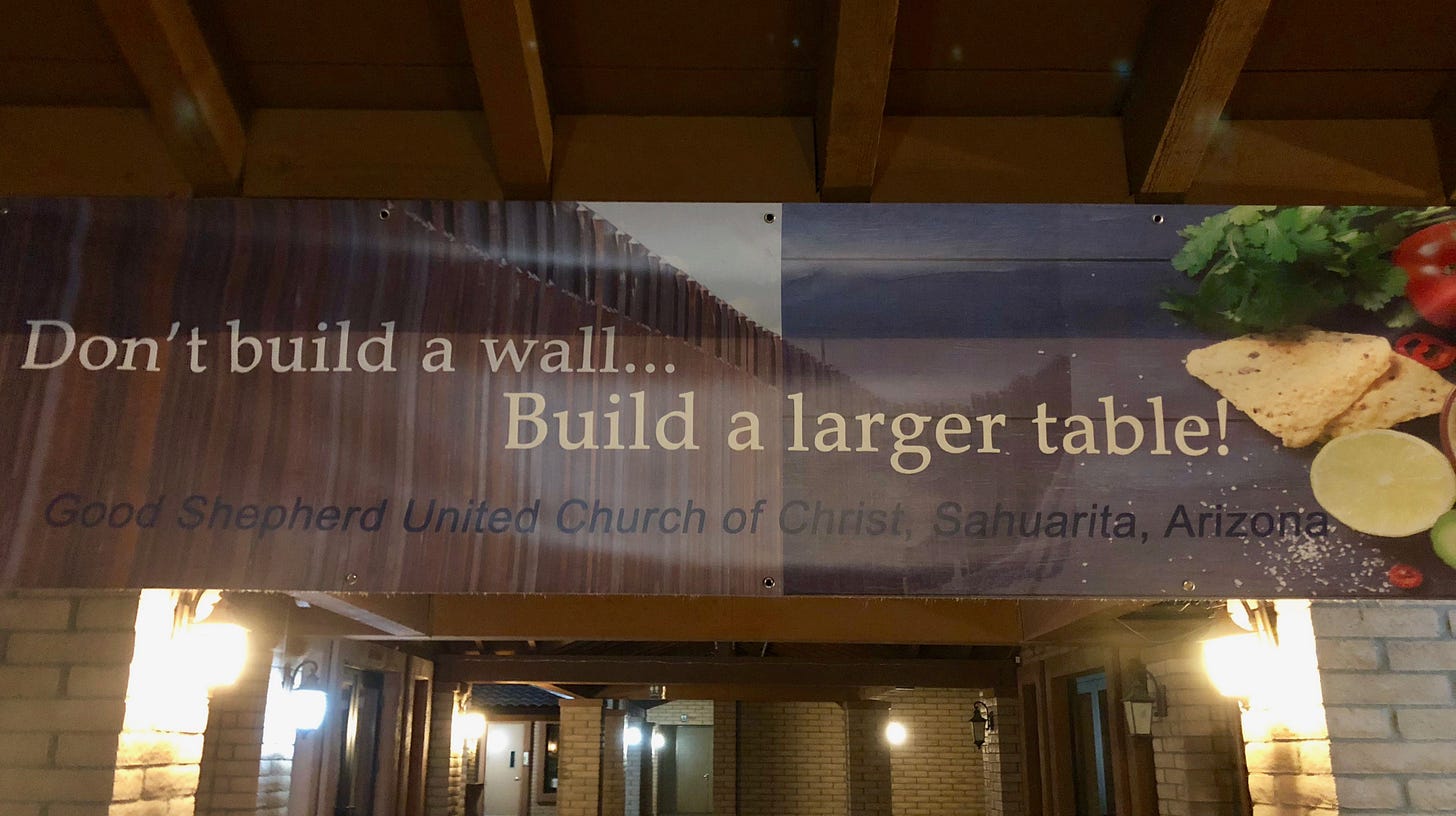

There is a potent political message in her “and”: a candidate whose life embodies a bridge counterposed to a President who based his previous campaign on building a wall. This election is about choosing between bridges and walls. Do we want to span that which seems impossible to connect or strengthen the fortifications that separate?

Most people think Christianity is necessarily part of the wall-building enterprise. Indeed, some call for a “Christian America,” a thinly veiled desire for a white, religiously unified state. Many believe that to be a Christian means to reject other religions – to follow a singular way with an exclusive savior. Church membership requires adherence to creeds and particular dogma that proclaim Christian superiority over and against other – and lesser – prophets and teachers. “Bridge” is not the infrastructure associated in popular culture with “Christian.” Wall, fortress, moat, yes. Bridge, not really.

This would have been a big surprise to the early Christians, those who took up the new faith in the years following Jesus’ death. They proclaimed a creed. But it wasn’t the familiar creed that most Christians know from church. The first creed was thus:

For you are all children of God in the Spirit.

There is no Jew or Greek;

There is no slave or free;

There is no male and female.

For you are all one in the Spirit.

If these words sound familiar, they appear in Galatians 3:28, a verse in a letter by Paul, and one of the oldest texts in the New Testament. In a recent book, The Forgotten Creed, biblical scholar Stephen Patterson argues that Paul did not write them. Rather, Paul borrowed this phrase from an even older source – most likely the first Christian baptismal liturgy. When new followers joined the Jesus movement, the words were repeated to those about to be baptized: You are all children of God. There is no Jew or Greek; There is no slave or free. There is no male and female. For you all one in the spirit.

This was powerful. The ancient Roman world was even more divided than ours. It was a society of hierarchies where certain ethnicities were privileged, people who were free were deemed fully human and slaves considered as beasts, and men were always superior to women. Bigotry, slavery, and sexism were the coinage of the Roman Empire. Jesus challenged all this by welcoming sinners and outcasts, by eating with people deemed unclean, and insisting that those who were last would be first.

The original believers embraced his radical social message – something we know because they were killed by the state as traitors. They were, as Patterson says, “committed to giving up old identities falsely acquired on the basis of baseless assumptions – Jew or Greek, slave or free, male or female – and declared themselves to be children of God.”

The first Christian creed – the long-forgotten creed – wasn’t about God. It was about us. Who we are, who matters, and who deserves dignity. The first creed was a statement of human solidarity. The Jesus movement grew from a community who dared to proclaim that “there is no us, no them. We are all children of God,” writes Patterson. “It was about solidarity, not cultural obliteration.”

We are all children of God.

You and

your neighbor and

immigrants and

believers of other faiths and

Democrats and Republicans

… and … and … and …

We are all children of God.

It doesn’t sound like any Christianity we know. But it is what Jesus preached. What Paul shared in his letters. And it was what the first Christians gave their lives for – a world of human dignity and equality for all children of God – where walls are torn down and bridges built in their stead.

And if that’s what a “Christian America” could mean, then count me in.

THE COTTAGE is published on Monday and Thursday, with occasional weekend specials. Sign-up for free, never miss an issue, and be part of the community.

All religions. All this singing. One song. Peace be with you. ― Rumi

A beautiful article. While I/we can differ on specific points, the essence is in our common essential love/faith. That, to me, is what is important it is our hearts moving together.

and isn't it fun that in Spanish a singlle Y brings the two sides even closer.