Discover more from The Cottage

Lent begins on Wednesday, February 22. During this six-week spiritual season, The Cottage will be exploring the stories of people who encourage us to live with joy and justice, and to pursue meaning and courage. We aren’t going to be talking about sin. We’re going on a journey to discover the “saints” that speak to us in this cynical age.

You can find all the Lent details below, at the bottom of this post after the poems. Make sure you are appropriately signed up. Invite a friend — or two.

Today’s post explores the connection between two studies in the news this week — one on the emotional state of America’s teen-agers and the other about Christian Nationalism. Are the two connected?

Read on. I make a case for seeing the whole picture that you won’t find anywhere else.

This week, news outlets across the nation reported on a newly released study of America’s teens: the Center for Disease Control’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). The findings were stark and frightening. American girls and LGBTQ teens “are experiencing extremely high levels of mental distress, violence, and substance use.” Indeed, the crisis is particularly urgent among teenage girls. “According to the data,” reads the report, “teen girls are confronting the highest levels of sexual violence, sadness, and hopelessness they have ever reported to YRBS.”

One in five girls reported sexual violence in the last year; one in ten reported that they had been raped; three in five said they are depressed; four in ten have considered suicide; and one in ten attempted to end their own lives.

The girls are not okay.

A few days before the CDC study, Public Religion Research and Brookings also released their long-anticipated report on Christian Nationalism in America. (Full disclosure: I was on PRRI’s board for a decade.) The report measures definitions and the extent of Christian Nationalism while examining how it intersects with race, gender and sexuality, antisemitism, Islamophobia, and violence.

The findings confirm what many people suspected: “White evangelical Protestants are more supportive of Christian nationalism than any other group surveyed. Nearly two-thirds of white evangelical Protestants qualify as either Christian nationalism sympathizers (35%) or adherents (29%).”

Amid the findings are a battery of questions related to gender and views of patriarchy. Christian Nationalists (the majority of whom are white evangelicals) believe women must submit to men, society is diminished when women have more opportunities to work outside of the home, men are being “punished” for “acting like men,” and America has become “soft” and feminized.”

In effect, these questions reveal how a particular interpretation of some verses in the Bible are shaping a political movement. Indeed, these four points reflect a position about gender know as “complementarianism,” a view widely-held by evangelical Christians. Complementarianism is the view that men and women have divinely ordained — and yet “complementary” — roles in society, church, and the home.

Most of the secular news stories reporting on the crisis among American girls found it difficult to pinpoint a source for the increase in depression, anxiety, violence, and suicide. A few traced the changes to the pandemic (although the trends began before that); some blamed social media bullying; and others suggested that all teenagers are suffering but that girls were more likely to report their pain. The Washington Post quoted a Harvard professor saying that there was no “single cause,” citing instead an complex of “interacting” causes.

Not a single mainstream media report suggested that there was a relationship between the CDC findings on girls and LGBTQ teens, Christian Nationalism, and the traumatic political climate created by white evangelicals and their commitment to Donald Trump.

* * * * *

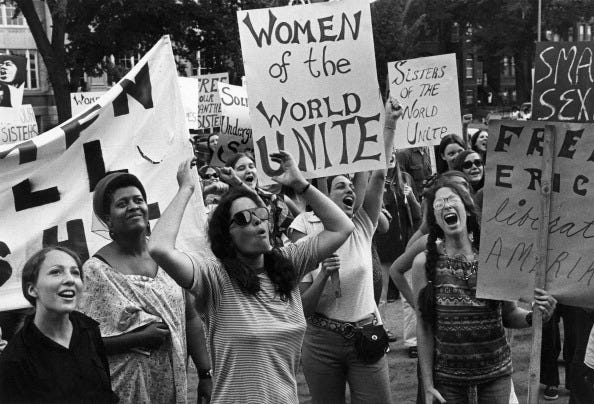

There is little doubt among historians that second wave feminism of the 1970s improved the lives of women and girls in terms of education, health, work, finances, and overall equality. Most of us who lived through those decades know how much things changed for women and that we experienced a genuine expansion of rights and equality. Those were heady days of liberation.

Some of America’s churches embraced the changes — if only after a fight — and opened clerical and theological leadership to women. And, although it is mostly forgotten today, even evangelical women proclaimed a new gospel of feminist equality. In 1974, Letha Scanzoni and Nancy Hardesty released All We’re Meant to Be: A Biblical Approach to Women’s Liberation. The book caused a sensation in evangelical churches and theological circles.

That same year, evangelical women founded the Evangelical Women’s Caucus to teach and celebrate Christian feminism — and they lobbied for the ERA, gender-inclusive language, and women’s ordination. Put simply, evangelical women weren’t that far behind their more liberal Protestant cousins and the Catholic sisters who were pressing their faith communities toward more expansive rights — religiously based rights — for women’s full equality.

The backlash among evangelicals, however, was swift. (Oddly enough, it has always seemed to me that the Catholic backlash wasn’t as quick or effective. That was mostly due to Catholic sisters and the unique place they hold in Catholic life.) The work of feminists like Scanzoni and Hardesty was drowned out by traditionalist Christian women like Elisabeth Elliot, Anita Bryant, Marabel Morgan, and Phyllis Schlafly (who was a Catholic but was beloved of evangelicals who hated the ERA).

Sending out evangelical traditionalist women to battle evangelical feminism was a devious strategy to unwind the growing influence of biblical feminism in evangelical churches. But there was, perhaps, nothing more pernicious or more influential than constructing an anti-equality backlash in the late 1980s called “complementarianism.”

Complementarians claimed scripture to be on their “side” of the theological arguments around women’s equality and feminism. In recent decades, millions of Americans have grown up in churches proclaiming complementarianism is the ancient, faithful view of orthodox Christianity since the the time of Jesus and Paul.

But it isn’t. “Complementarianism,” as a theological term, was coined in 1987.

That’s right: 1987.

I know. I was there. Well, sort of.

In 1986, the Evangelical Women’s Caucus held an unusually contentious meeting. In a overwhelmingly supportive vote, the membership passed a resolution supporting the lesbians in their midst:

Whereas homosexual people are children of God, and because of the biblical mandate of Jesus Christ that we are all created equal in God's sight, and in recognition of the presence of the lesbian minority in EWCI [Evangelical Women's Caucus International], EWCI takes a firm stand in favor of civil rights protection for homosexual persons.

As a result of the vote, a number of the women who taught at conservative evangelical colleges and seminaries withdrew and formed another — and anti-LGBTQ rights — Christian feminist group: Christians for Biblical Equality.

But anti-feminist evangelicals had had enough. They’d always accused evangelical feminists of a slippery-slope — women’s liberation would lead to lesbianism. And, in their minds, the 1986 meeting proved the point. Something more needed to be done to stop “biblical” feminism altogether.

In 1987, a group of anti-feminists met in Danvers, Massachusetts and drew up the first draft of a theological statement of “completementarianism” that rejected in full any sort of biblical egalitarianism. The Danvers Statement was their response to evangelical feminism — and they were committed to aborting any and all forms of theology that would support women’s equality. To do so, they literally invented complementarianism.

I said that I was there — sort of. At that time, I was a student at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, in the next town over from Danvers. Somehow, we students got wind of the meeting and the early draft of the statement. Before we knew it, some of our classmates were suddenly using the language of “complementarianism,” a word none of us had previously heard — and were insulting egalitarianism as a heresy. The official Danvers Statement was released in spring 1988. But, at the seminary, the argument had already begun. It was a little like witnessing the beginning of a war. Little did I know, I’d eventually be one of its victims. (But that’s another story.)

* * * * *

The impact of the Danvers Statement and complementarianism was huge. Back in 1988, my friends and I couldn’t imagine evangelicalism without feminism. We’d thought it had won the day — and we considered the “complementarians” cranks and theological throw-backs.

But the backlash was strong, much more than we could have guessed. The hierarchal crusaders were committed to total victory. Within a decade, they’d wiped out the memory of biblical feminism. Evangelical complementarians joined forces with Phyllis Schlafly to defeat the ERA and embraced Rush Limbaugh and his attack on “femi-Nazis.” Together, conservative evangelical Christians and secular anti-feminists constructed one of the most successful political backlash movements in American history. (The political backlash against women in the 1990s and the aughts was much more extreme than was noticed at the time.) The evangelical anti-feminist crusade reached it misogynistic culmination with the election of Donald Trump in 2016 and the defeat of Hillary Clinton.

And the continued impact of complementarianism and Christian Nationalism on American politics is clearly demonstrated in the PRRI/Brookings data.

This religious history is a significant factor contributing to why girls and LGBTQ teens are in crisis. Today’s teens have grown up amid the success of religious and political movements intent on taking away their freedoms, rights, and futures. The goal is to force them into their “complementary” assigned roles in kitchens and closets. Complementarianism and Christian Nationalism are twinned impulses, and neither wants girls, women, or LGBTQ teens to thrive.

I don’t think the two studies side-by-side are unconnected or simply coincidental. There are threads between them. They are of a piece, a single, smothering cloth.

It is no fun watching people undo your liberation, especially when you are young.

Honestly, I get depressed about all this, too. But I was vaguely encouraged this week when Russell Moore of Christianity Today published a somewhat repentant editorial against complementarianism this week. In it, he recognized that, “recent scandals have demonstrated that the. . . arguments of egalitarians were at least partially right — by pointing out that, for some, what lay behind a zeal for ‘male headship’ was not responsibility before God but a psychologically stunted loathing of women or, worse, a cover for the sadistic silencing of women and girls.”

“Sadistic silencing” from Christianity Today? Apparently, Russell Moore now sees the connection, too. For that, I am grateful.

We can reclaim lost territory; we can claim the theological high road again. But it is going to take a lot of work. And it will help to know the history that has brought us here. We need to understand the past to change the future.

We owe it to the girls. And to their LGBTQ peers. Their well-being — their hope — depends on us.

INSPIRATION

There are so many roots to the tree of anger

that sometimes the branches shatter

before they bear.

Sitting in Nedicks

the women rally before they march

discussing the problematic girls

they hire to make them free.

An almost white counterman passes

a waiting brother to serve them first

and the ladies neither notice nor reject

the slighter pleasures of their slavery.

But I who am bound by my mirror

as well as my bed

see causes in colour

as well as sex

and sit here wondering

which me will survive

all these liberations.

— Audre Lorde, “Who Said It Was Simple”

I’ll tell you where I think what you called “courage” or bravery comes from. As a “spunky kid,” one of my earliest phrases was, “That’s not fair!” about any injustice. I applied that to girls and women and to other marginalized groups. That was my thing: it’s not fair. I think the courage came from asking, “What is just?” People have to know what is just and what is fair. Some have said that the word “righteousness” in Scripture is really— in the New Testament, how the Greeks used it — justice. So that’s it: wanting fairness for all people, for all groups; that’s where my courage comes from.

— Letha Scanzoni

Although many right-wing Christians despise what I have done with the keys they put into my hand, the fact is that the same Bible that deeply oppressed me has also been the most vital element in setting me free.

— Virginia Ramey Mollenkott

My grandmothers were strong.

They followed plows and bent to toil.

They moved through fields sowing seed.

They touched earth and grain grew.

They were full of sturdiness and singing.

My grandmothers were strong.

My grandmothers are full of memories

Smelling of soap and onions and wet clay

With veins rolling roughly over quick hands

They have many clean words to say.

My grandmothers were strong.

Why am I not as they?

— Margaret Walker, “Lineage”

LENT STARTS ON FEBRUARY 22

This Lent, The Cottage explores the EMPTY ALTARS of our days.

We are living in a time of iconoclasm. We've stripped the altars of both state and church. America's spiritual landscape is now marked by empty altars everywhere.

What does it mean to live in such an age? And what comes next? Will we put up new icons? Who are saints and heroes who speak beyond our cynicism? Who can inspire us to move ahead with joy, hope, and courage? Can we reimagine the sacred spaces in which we live?

We’ll explore EMPTY ALTARS in TWO WAYS:

1. WEEKLY DEVOTIONAL REFLECTIONS and conversation threads for paid subscribers at The Cottage. “Empty Altars” is the theme of my next book project — so you’ll be getting a preview of what I’m working in the form of inspirational material for your Lenten journey.

If you aren’t already a paid subscriber and want to receive the Empty Altars devotional reflections, please upgrade here:

2. An EMPTY ALTARS online class with me and Tripp Fuller. The Cottage and Homebrewed Christianity are teaming up once again for a mind-blowing, heart-expanding class this Lent — and our focus this year is history, spirituality, and social change. The course will begin on Monday, February 27. THE CLASS REQUIRES A SEPARATE SIGN-UP HERE — and is offered for free. Voluntary donations are welcome.

* * *

If you want the ENTIRE EXPERIENCE, make sure you are registered for the class AND have a Cottage paid subscription. The registration and the subscription will give you full access to everything!

Of course, you are welcome to do one without the other — they are complimentary explorations but each is beneficial on its own.

I didn't mention this in the piece, but probably should have.

The Danvers Statement was crafted in Danvers, MA in 1987 (as I did say). Three hundred years earlier, in 1692, Danvers was called "Salem Village." It was the site of the first accusations of witchcraft in the notorious Salem Witch trials. Both of these Danvers episodes are part of the long history of religious extremism, misogyny, and violence against women in American history.

I wonder if those who wrote the Danvers Statement knew they were on the same ground as the witch hunters of centuries before? Historical accident? Or strangely cruel parallel?

Just wondering out loud here.

Thank you for this important post, Diana. I'm working on an article about the misogynist texts of the NT that are used to disempower women and thought some may find this info helpful. This is specifically around the hurtful language of 1 Timothy:

Scientific analysis has shown that the language in 1 Timothy is not consistent with Paul's other writings. The words are inconsistent with Paul’s regular vocabulary, but rather are reflective of Second Century Christian writing. The writer also appears to be concerned with an early form of Gnosticism, which as many know came after Paul’s life.

1 Timothy also speaks of a church structure or hierarchy that wasn’t in place during Paul’s life. Paul’s original churches likely had no one single leader or pastor. Paul never expected his churches to last bc he believed strongly the return of Christ was imminent. The hierarchy of churches is a later development as it eventually became clear Christ wasn’t returning soon.

So women are not allowed to speak in church in the Pastoral letters. Yet Paul’s authentic letters speak otherwise. (The one exception is 1 Cor 14 and the authenticity of this verse debated, as it appears to be a later scribal insertion, and upon close inspection it seems as if it’s inserted in the midst of a passage about prophecy. My understanding is that in another early manuscript this same verse is also found in another place inserted after verse 40, so it appears to not be original and to have been added later.)

And in 1 Cor 11 Paul says women can speak in church. So Paul was actually pro-women. In Romans 16 Paul mentions women missionaries, Prisca and Perseus, and a woman deacon, Phoebe, and a woman Junia, a foremost apostle.

So how do we explain this? The influence of women within the church waned as time passed in the mid to late First Century and early Second Century. Women would’ve originally had a strong presence in house churches, but lost their authority as the church became more public. Thus this is the reason someone forged the pastoral epistles to undermine Paul’s earlier writings which demonstrated the equality and importance of women in the churches. To think of Paul as a perfect source for what God wants is undermined by the fact Paul expected to see Jesus return in his own lifetime.

There is tremendous freedom in moving beyond a need for a perfect Bible that so many Christians cling to. I used to do those mental gymnastics too. I understand it as well as anyone. Losing the idea of a perfect Bible sent me into a tailspin and I thought I would lose my faith completely at first, and those were challenging times. But God is so much greater, and also so much simpler than that. God loves all of us equally and we all have an equal part to play in spreading God's love.

Hope everyone has a great week.