Discover more from The Cottage

The Cottage is a newsletter and a community — a place to reflect on faith with passion and explore contemporary issues through lens of theology and history. It is about heart and head, compassion and challenge. This is part of the new ecology of writing — where readers support ideas and authors directly, and where writers build relationships with readers. I’m glad you are here. And, as always, I invite you to consider contributing financially to the Cottage.

September 22 marks the seventh anniversary of the death of Phyllis Tickle (1934 –2015), remembered for her contributions to religious publishing and as an author in her own right.

But I think of her as a prophet.

In the last years of her life, Phyllis wrote the most influential book of her career: The Great Emergence. She invited Christians to think about the future of their traditions, theology, congregations, and spiritual practices. She was honest about what was ending and celebrated what was being newly birthed among us. That was her genius and joy — her unrelenting optimism about the future of faith. It was glorious to see her, in her mid-70s, speak about church and the future in a roomful of younger people with hope and confidence. Her exuberance for what could be coming earned her the nickname, “Evangelist of the Future.”

It was a privilege and honor to be one of her thought partners on that journey. We first met in 1998, when I was 39 and she was 64, and we worked together for the next seventeen years. She was a formative influence on my writing career and a trusted friend. I can’t remember how many times we shared a stage or followed one another in a pulpit. Most of it has melded into an embracing, expansive memory of “Adventures with Phyllis.”

But this week, one particular event came to mind. In 2010, she and I were invited to speak to the entire house of bishops of the Episcopal Church about the “emerging church.” (Aside for my Episcopal friends: the Rev. Stephanie Spellers led worship for this gathering.) It was a remarkable event that generated some of the most insightful and hopeful conversations I’ve ever had with denominational leaders. I felt energized — and believed that genuine institutional change would result from the work we’d done.

After the event, Phyllis and I drove back to the Houston airport together — and what happened in the car surprised me. I remarked on how well it had gone. And Phyllis replied, “It seemed to.” She paused, “I hope they listened. I’m not sure they realize how little time they have left.”

“What?” I asked, more than a little shocked.

“If you really look at the numbers, mainline churches don’t have much more than twelve to fifteen years left. The Episcopal Church is doing some things well. Maybe they’ve got a little longer.” The sentence hung in the air. “There’s not much time to change the future.”

I didn’t know what to say.

And I didn’t know how long she’d been thinking that the future was closer than most people imagined. Her predications for evangelical churches weren’t much brighter. In the decade we’d known one another, that airport drive revealed the most worried and least optimistic Phyllis I’d ever heard.

And, in the next five years, I’d hear her say it out loud. At clergy conferences, seminary gatherings, and publishing conferences. With wit and a smile, she’d warn her friends and critics alike: time is short.

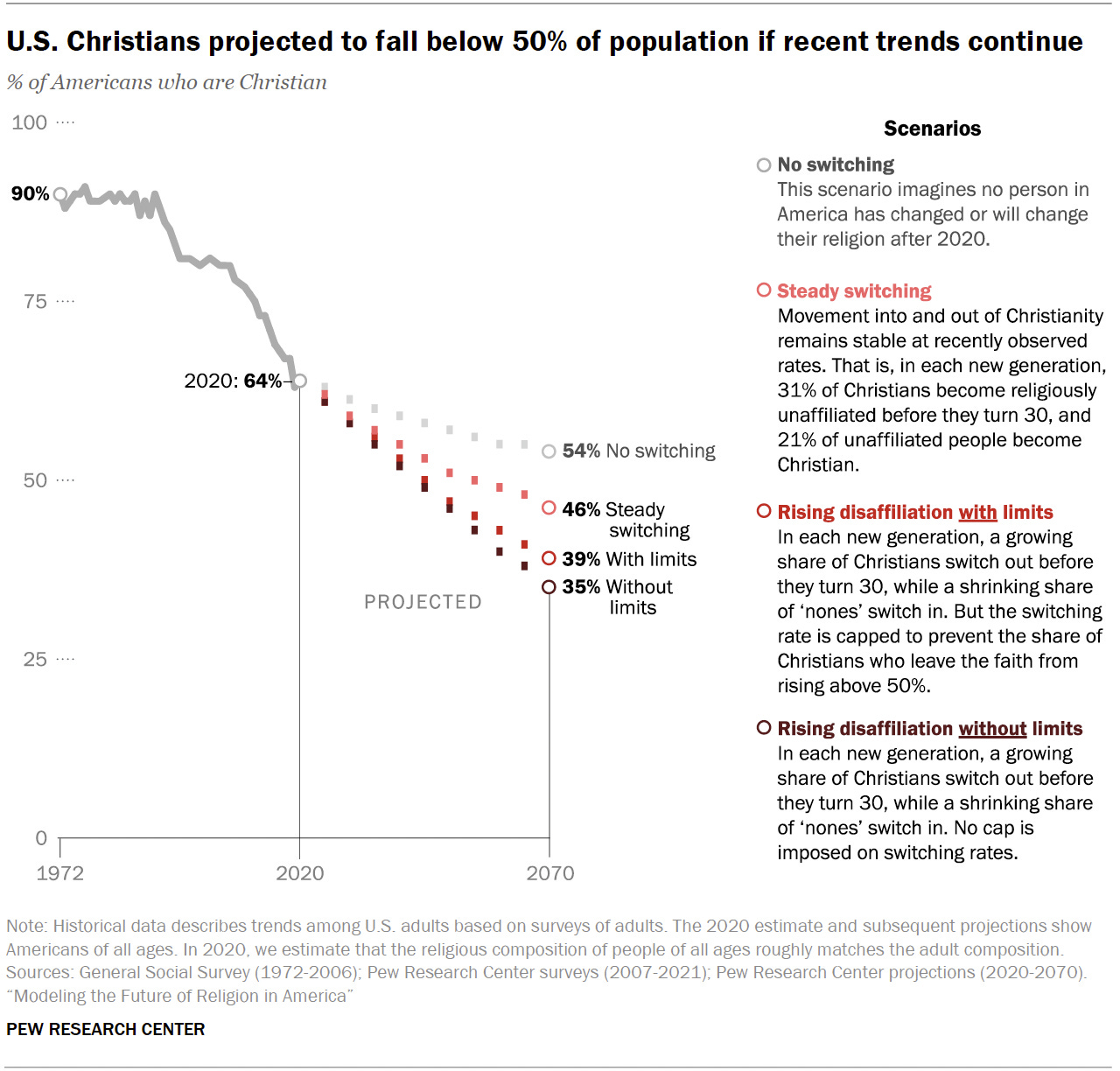

This week — the same week in which Phyllis died seven years ago — Pew Research released a report modeling the potential future of Christianity in the United States. While Phyllis worked on intuition and experience to think about the future (less data was available even a decade ago on these trends), Pew developed a model to draw four possible futures for American Christianity and released the report a few days ago.

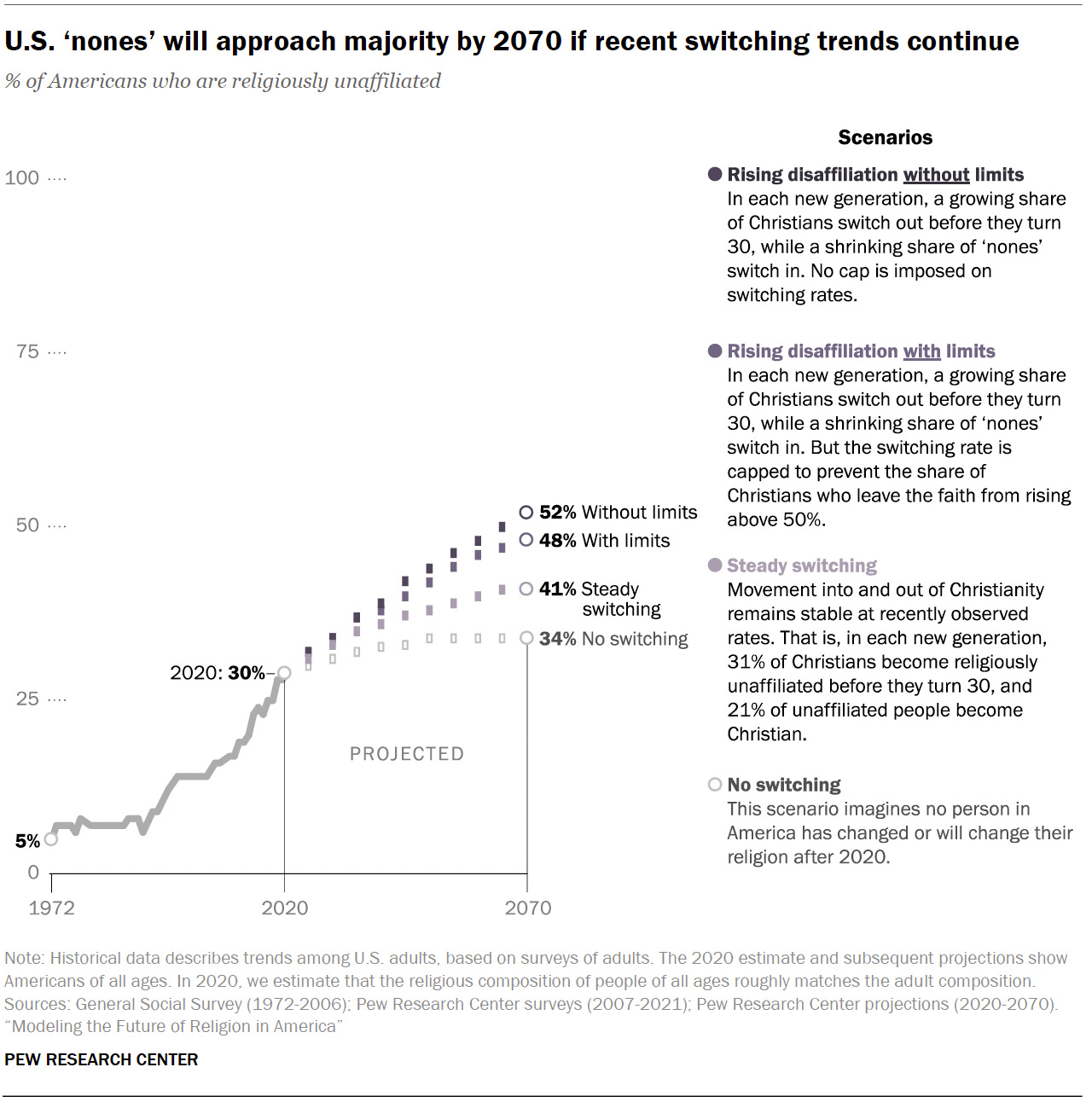

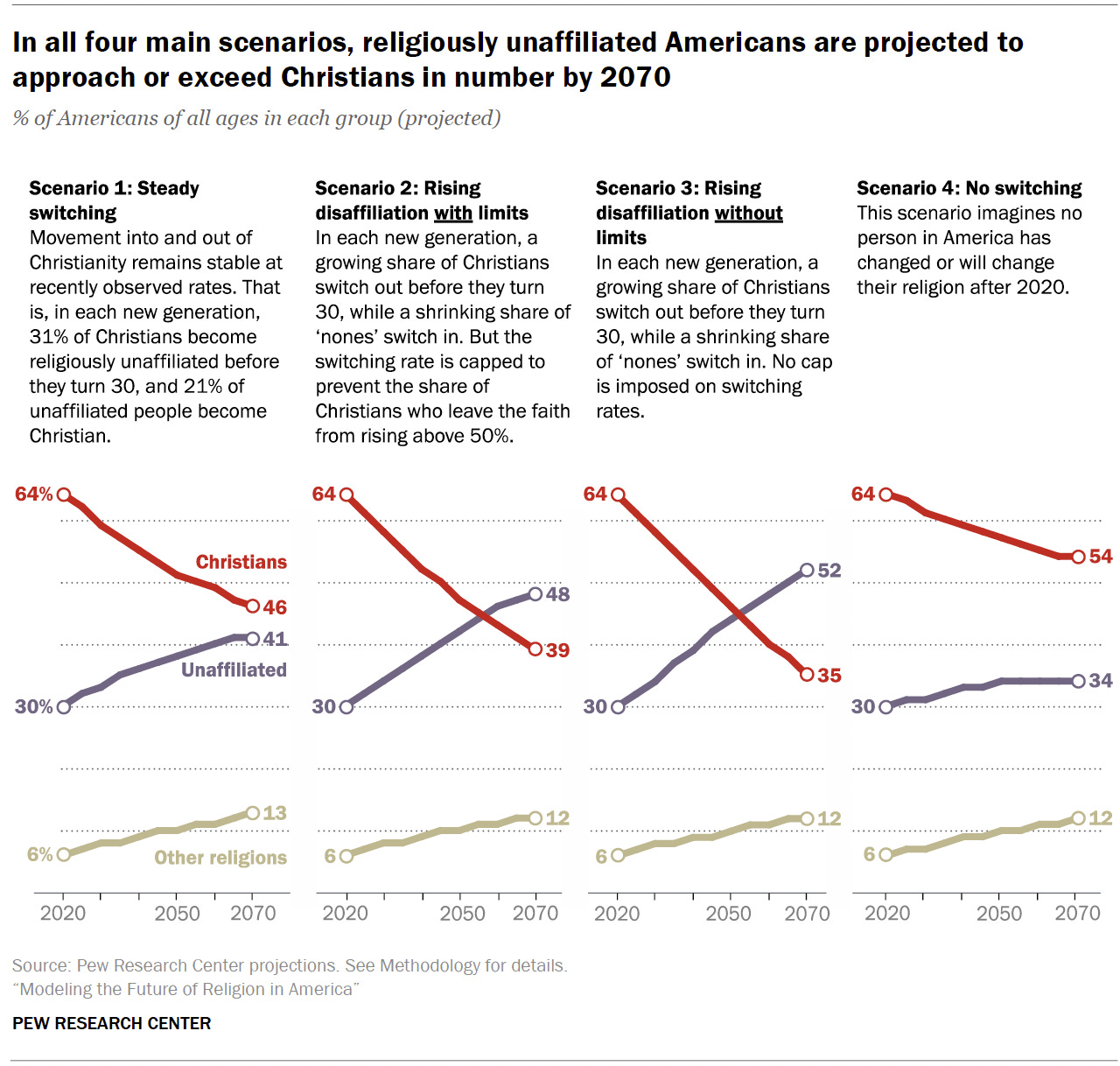

Pew’s conclusion? By 2070, Christianity in the United States (the whole thing — all forms of Protestantism, Catholicism, and Orthodoxy, all racial and ethnic Christian communities in a single category) will be a minority faith in a nation with a majority of “nones.”

The study states:

While the scenarios in this report vary in the extent of religious disaffiliation they project, they all show Christians continuing to shrink as a share of the U.S. population, even under the counterfactual assumption that all switching came to a complete stop in 2020. At the same time, the unaffiliated are projected to grow under all four scenarios.

The Pew research team insists that they aren’t prophets, and that their formal demographic models are not set in stone — “These are not the only possibilities, and they are not meant as predictions of what will happen. Rather, this study presents formal demographic projections of what could happen.”

Yet they are also convinced that all their probable futures result in a far more religiously diverse America with a minority Christian population. “Of course, it is possible that events outside the study’s model – such as war, economic depression, climate crisis, changing immigration patterns or religious innovations – could reverse current religious switching trends, leading to a revival of Christianity in the United States. But there are no current switching patterns in the U.S. that can be factored into the mathematical models to project such a result.”

Their research is summarized in three charts:

Perhaps 2070 seems a long way off — anything could happen between now and then. But, when you are trying to re-imagine and re-structure large religious institutions with complex histories and traditions, fifty years isn’t much time to prepare and retool them for a future of being a minority in a largely secular nation. Indeed, most churches probably should have started this process with honesty and courage at least a decade ago.

In short, Phyllis was right. The Pew study shows that probability has finally caught up with the prophet.

I hope people will listen. Demographics are not destiny; trends are not predestination. Although Christianity probably will be a minority faith in a much more pluralistic nation in the next few decades, those of us who are Christians still have much work to do in advance of that huge, historic shift. Denial is a terrible strategy. Nostalgia is a dangerous choice. Letting the future take its own course is a kind of surrender of responsibility.

What will be the shape of the Christianity in that future America? Will we welcome how different it will be or fight it? Will Christianity be part of the problem of our political future or contribute to a flourishing pluralistic democracy? How Christians respond to both prophets and probabilities of the future is a big deal — not only for our children and grandchildren, but for American Christianity right now. The choices that this generation makes impress themselves on those who will follow us.

Because the future is right around the corner.

INSPIRATION

The rising hills, the slopes,

of statistics

lie before us.

the steep climb

of everything, going up,

up, as we all

go down.

In the next century

or the one beyond that,

they say,

are valleys, pastures,

we can meet there in peace

if we make it.

To climb these coming crests

one word to you, to

you and your children:

stay together

learn the flowers

go light

— Gary Snyder, “For the Children”

About every five hundred years the Church feels compelled to hold a giant rummage sale. . . We are living in and through one of those five-hundred-year sales.

― Phyllis Tickle, The Great Emergence

Religion, whether we like it or not, is intimately tied to the culture in which it exists. One can argue — with only varying degrees of success, though — that private faith can exist independent of its cultural surround. When, however, two or three faith-filled believers come together, a religion — possibly more of a nascent or proto-religion — is formed. Once formed, it can never be separated entirely from its context. Just as surely as one of the functions of religion is to inform, counsel, and temper the society in which it exists, just so surely is every religion informed and colored by its hosting society. Even a religion’s very articulation of itself takes on the cadences, metaphors, and delivery systems of the culture that it is in the business of informing. Thus, when we look at these semi-millennial tsunamis of ours, we as Christians must be mindful of the fact that the religious changes effected during each of them were only one part of what was being effected, and that all the other contemporaneous political, social, intellectual, and economic changes were intimately entwined with the changes in religion and religious thought.

― Phyllis Tickle, The Great Emergence

News stories about the Pew report (some may be paywalled):

Religion News Service

Deseret News (Salt Lake City’s newspaper has first-rate religion coverage)

NPR (an interview)

Christianity Today

So good to remember Phyllis. I was just citing her Great Emergence book to a group in Kalamazoo, MI, this afternoon. Curiously, the more dire things get for the future of Christianity, the more hopeful I become. I think there is a major shift coming - indeed, already upon us. All of the perennial traditions are struggling to comprehend what's happening, and all paths up the proverbial mountain have become faint or lost altogether in the Great Storm of modernity/post-modernity. But this lostness, coupled with the advent of technologies that knit us more closely together (even as some drive us apart), are bringing the world's perennial traditions closer to one another. It used to be that only the mystics saw that the religions were different paths up the same mountain, and that while they are all truly different paths, they are ultimately united at their highest level of realization. Now, thanks to the internet, global travel, etc., you don't have to be a mystic to have access to this realization. I predict that as things get worse, the perennial traditions will draw closer and closer together. Not forming a single "world faith," but helping each other expand their views of their own faiths as well as that of others. Through this greater contact, the paths that have been faint or obliterated will become more clearly seen, allowing for the possibility of all the world's perennial traditions (and many more besides) to move to the next level of their journey. As Ilia Delio insists, Christianity is, a religion of evolution. It definitely is, if we believe there is such a thing as the Holy Spirit, or the Living Presence of Christ. Evolution doesn't take place without lots of deaths and resurrections, and an embrace that God is indeed "still speaking" in the world.

I'm finishing up a presentation for a educators in youth ministry conference and allude to her work. She was such a joy to be around. Those emergent years very formative to me and what I've been working on these past few years. I hope she and her work will continue to be used/highlighted/remembered/revered as we move forward in this great rummage sale.