Discover more from The Cottage

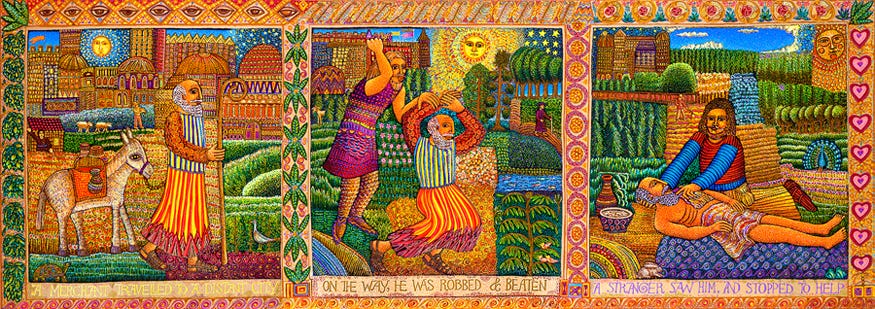

On this Sunday, the lectionary offers a familiar story — the parable of the Good Samaritan — arguably one of the most memorable and widely quoted texts in the New Testament.

Luke 10:25-37

Just then a lawyer stood up to test Jesus. "Teacher," he said, "what must I do to inherit eternal life?" He said to him, "What is written in the law? What do you read there?" He answered, "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself." And he said to him, "You have given the right answer; do this, and you will live."

But wanting to justify himself, he asked Jesus, "And who is my neighbor?" Jesus replied, "A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a priest was going down that road; and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan while traveling came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with pity. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, having poured oil and wine on them. Then he put him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him. The next day he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said, “Take care of him; and when I come back, I will repay you whatever more you spend.” Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?" He said, "The one who showed him mercy." Jesus said to him, "Go and do likewise."

The flannel graph board was blank except for three colors — soft blue fabric for sky, green for the ground, and a thin brown stripe for a road. Miss Jean, my Sunday School teacher, called us to gather in a circle. She reached into a box and drew out a man cut from felt. “A traveler was walking down the road,” she moved him back and forth to imitate a stroll, “when some robbers attacked him, took his clothes and money, and threw him in a ditch.”

She pressed the felt victim onto the board in a prone position. She pulled more figures from the box. A priest, then a Levite (what’s a “Levite,” I wondered?) passed by without helping the man. Then, a fabric Samaritan with a cut-out donkey came down the road. He stopped and picked the injured man up, gave him a drink and bandaged his wounds. Miss Jean peeled the prone felt character from the board and placed him on the donkey. She continued, saying that the Good Samaritan “took the man to an inn and cared for him.”

“Who would you like to be?” she asked. She held up the felt priest; then the Levite. No takers. And then, she removed the Samaritan from the board and showed him to us. “Him?”

We all raised our hands.

It may well have been one of the easiest questions I’ve ever been asked. Everybody wanted to be the Good Samaritan. Of course.

* * * * *

A few years ago, I was riding a steep escalator up from the Dupont Metro stop in Washington. About twenty steps ahead of me was an elderly man. He suddenly cried out and crumpled, tumbling down the moving stairs, until his limp body reached the step above me. He was bleeding, I knelt down — while we were still moving toward the top — and tried to comfort him. Then, realizing the extent of his injuries, I yelled for help.

Before I knew it, a thirty-something young man was at my side. As we approached the escalator’s end, he lifted the dazed man so his body wouldn’t get caught in the mechanism. We found a bench, sat the wounded man down, and tended to him. A few others joined us, a waiter from a nearby restaurant brought paper towels, someone had a bottle of water. The man tried to walk away, insisting it was nothing and that he was fine. All the while blood ran down his face from a gash in his forehead. We called an ambulance. He asked for prayers — that I could do! — while our impromptu band of Good Samaritans waited for the professionals to arrive. Once they did, we all shook hands and went on our separate ways.

About three weeks later, I was crossing a street in Alexandria, the town where I live outside of Washington. It is a much less hectic and friendlier place than downtown DC. I tripped, landing spread eagle in the crosswalk. My purse flew one direction, my glasses another. My hands were scuffed and bleeding from my feeble attempt to break the fall. And my knee was hurt. Dazed, I looked up, and saw that the crosswalk signal was about to change. I couldn’t pull myself together in time to get out of the road before the light turned green. I started to cry, searched for my glasses, and hoped for help.

A car stopped, and a woman opened the driver’s side door. I felt relieved — someone was going to assist me. Instead of helping, however, she began to yell at me: “What’s wrong with you? Get up! You’re blocking traffic!” When I didn’t answer, she shouted, “Are you deaf?” and she leaned on her car horn. I crawled across the street to the far corner. “Idiot,” she shouted as she drove away. I sat on the curb sobbing. No one asked me how I was; no one helped. Several people walked by without comment, turning their gaze away from the rattled woman on sidewalk.

And that’s the thing about this parable. Occasionally, you get to be the Samaritan. But sometimes you’re in the ditch.

* * * * *

Sunday school didn’t alert me to this possibility. Instead, the flannel graph led me to believe that nice Methodist children should always choose to help. It never occurred to me that I could wind up in the ditch. We were always the do-gooders, not the victims.

Honestly, it felt virtuous being a good Samaritan. In spite of the fear and horror engendered when the man fell on the escalator, helping him made me feel useful. It was rewarding. It was gratifying that I wasn’t the only one to assist. The community of care we formed on that day seemed holy, as strangers came to the aid of another stranger — none of us knowing the names of the others — none knowing what brought all the others to Dupont Circle that day — none marked by political party or religious affiliation. In other circumstances, we might have thought of each other as rivals or, perhaps, enemies. But at the that moment, we had a single goal — to save an injured traveler. It was as things should be, the everyday miracle of helping.

But it felt terrible to be the victim. Not only did the fall hurt, but I was shocked by the response of all those around me. That woman yelling. People ignoring my pain. Wondering if some inattentive driver would run me over while I struggled in the road. Reaching for my glasses, unable to see clearly. My sense helplessness quickly turned to fear and then, unexpectedly, anger. After all, I’d recently been a good Samaritan. When I needed someone, however, no one was there. I had to help myself.

Some people will always pass by — even if they don’t want to admit it to their Sunday school teachers. Many people will help. But, sooner or later, we’ll all be in the ditch. And there, in that utterly dependent position, we see everything differently.

Splayed on the road, I didn’t care who helped me. I just needed help. And that’s the real point of the parable. Amy-Jill Levine insists that Jesus’ first audience — Jewish hearers — would have identified more with the victim in the ditch than the Samaritan:

From the perspective of the man in the ditch, Jewish listeners might balk at the idea of receiving Samaritan aid. They might have thought, “I’d rather die than acknowledge that one from that group saved me”; “I do not want to acknowledge that a rapist has a human face”; or “I do not recognize that a murderer will be the one to rescue me.”

That’s what the Jews in Jesus’ day thought of the Samaritans — that they were descendent from rapists and murderers, collaborators with rulers who oppressed God’s people and who worshiped at a corrupt Temple. That’s who showed up as the hero in the story, the person who administered mercy — their enemy.

“Who is my neighbor?” asked the lawyer.

The answer? The very worst person you can imagine, Jesus responds. Your enemy.

* * * * *

I wonder how I would have responded if my fellow helpers at Dupont Circle were wearing MAGA caps. Would I have said, “I can do it myself! I don’t need your help to save this man!” Would I have walked away? Unwilling to make common cause with these objectionable people? Would it surprise me that they — of all people — would show mercy to a stranger?

I don’t wonder how I would have responded when I was in the ditch. I needed help. At that moment, I would have accepted the hand of Richard Spencer, the white supremacist leader who lived in Alexandria at the time, if he’d offered. You might say, “Never! He’d never reach out! He’s evil!” Perhaps not. There are no good Proud Boys.

But there was no such thing as a good Samaritan either. As Professor Levine notes, “To Jesus’ Jewish audience as well as to Luke’s readers, the idea of a ‘good Samaritan’ would make no more sense than the idea of a ‘good rapist’ or a ‘good murderer.’” Levine, who is Jewish, says that contemporary version of the parable would turn the Good Samaritan into the “Good Hamas Member.”

Would I take his hand or stay in the road with the driver who wanted to run me over? Honestly, a neo-Nazi helper would have been preferable to the respectable lady in the expensive car.

That’s the real story of the Good Samaritan. Whoever shows up — even your enemy — especially your enemy — is your neighbor.

* * * * *

Ultimately, the flannel board story proved theologically inadequate. As Methodist pre-schoolers, we didn’t understand about Samaritans. We truly believed he was good, a genuinely nice Samaritan. (And sadly, in contrast to those mean Jews — the antisemitic telling of this story to even three-year-old Christian children is reprehensible.)

Miss Jean’s felt-figure rendering of the parable has stayed with me for six decades, reminding me always to choose to help. But the lesson of the ditch — that extending mercy turns even mortal enemies into neighbors — would come much later.

And so, I’ve put Miss Jean’s simple question behind me.

Instead, I’m ruminating on these questions posed by Amy-Jill Levine:

Can we finally agree that it is better to acknowledge the humanity and the potential to do good in the enemy, rather than to choose death? Will we be able to care for our enemies, who are also our neighbors? Will we be able to bind up their wounds rather than blow up their cities? And can we imagine that they might do the same for us? . . . That biblical text — and concern for humanity’s future — tell us we must.

Sometimes, we’re the Samaritan in the story. But, even then, chances are we are also someone’s enemy. And that’s an important thing for every helper to realize.

Right now, however, most of us are in the ditch. Few of us were prepared for that. We’d much rather be helpers. Down here, we feel hopeless, hurt, afraid, and angry. We stare in shock at those who threaten to run us over if we don’t get out of their way. In the ditch, however, we have the chance to learn the most radical truth of all — even our enemy is our neighbor. The endless cycle of revenge and retaliation can be broken by only one thing: a hand extended in mercy.

*The Amy-Jill Levine quotes are from her book, Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi.

INSPIRATION

God of bandit places,

love that demands our all:

reveal to us our wounds

and give up grace

to know our neighbors,

tending us

with foreign hands.

— Steven Shakespeare

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of out-door game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.’ I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

— Robert Frost

On the parable of the Good Samaritan: I imagine that the first question the priest and Levite asked was: “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” But by the very nature of his concern, the good Samaritan reversed the question: “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”

That's the question before you tonight. Not, "If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to my job. Not, "If I stop to help the sanitation workers what will happen to all of the hours that I usually spend in my office every day and every week as a pastor?" The question is not, "If I stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?" The question is, "If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?" That's the question. Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge to make America what it ought to be. We have an opportunity to make America a better nation. And I want to thank God, once more, for allowing me to be here with you.

― Martin Luther King Jr., “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” April 3, 1968

“Love your neighbor as yourself” the Gospel says (Matthew 22:38). But who is my neighbor? We often respond to that question by saying: “My neighbors are all the people I am living with on this earth, especially the sick, the hungry, the dying, and all who are in need.” But this is not what Jesus says. When Jesus tells the story of the good Samaritan (see Luke 10:29-37) to answer the question “Who is my neighbor?” he ends by asking: “Which do you think, proved himself a neighbor to the man who fell into the bandits’ hands?” The neighbor, Jesus makes clear, is not the poor man laying on the side of the street, stripped, beaten, and half dead, but the Samaritan who crossed the road, “bandaged his wounds, pouring oil and wine on them. . . lifted him onto his own mount and took him to an inn and looked after him.” My neighbor is the one who crosses the road for me!

— Henri Nouwen

For Summer Wisdom Journey Participants:

On Monday, you’ll get this week’s text from Ecclesiastes. Tuesday is reflection day. Wednesday is the online chat (we had fun last week with the Proverbs passage). You’ll also get a mini-pod of a discussion on wisdom literature (release date TBA) with Professor Pete Enns, a Hebrew Bible scholar and host of The Bible for Normal People podcast. It should be a great week on the Wisdom Journey!

If you missed anything last week (including the online chat thread), paid subscribers can access the entire Summer Wisdom Journey in the Cottage Archive.

If you want to participate, you can still upgrade to a paid subscription by clicking the button below.

Thanks for the shout out -

also note that the tradition of hate can be broken. The parable is an alternative to 2 Chronicles 28.

Samaritans and Jews held mutual dislike, except when they did not. The mother of Herod Antipas was a Samaritan. The more we know of Jesus's Jewish context, the more profound his teachings sound.

AJ Levine

I am intrigued that I never thought of this story from the standpoint of my being the one in the ditch. Thanks for the new angle.