Today is Christ the King Sunday, the final Sunday of Pentecost. Advent begins next week.

In many ways, the celebration of Christ the King is one of the most conflicted feast days in the entire church year. It was first proclaimed by Pope Pius XI in 1925 to reassert the primacy of Jesus’ lordship over the rise of nationalism and authoritarianism in European politics. But, a few years later, that same Pope came to an agreement, the Reichskonkordat, with the Nazis that many historians believe lent moral legitimacy to Hitler’s regime.

The questions of God’s kingdom and its relationship to human governments are among the most contentious and difficult questions in the history of Christianity. Simply reasserting Christ as King over the politics of this world may seem an appealing solution to some in our own times. But this is the path now pursued by Christian nationalists, influenced by theologies seeking to “reconstruct” Jesus’ lordship and extend God’s dominion through political movements in the United States and across Europe.

Exploring the tensions inherent in all this would be a worthy essay (or book!). But my heart leaned in a different direction today — toward a story I told in Freeing Jesus of a time when I experienced the meaning of “kingship” in a kitchen.

And so, I share with you a memory from my own life when, as an idealistic young evangelical, I felt a call to become a missionary and spread the Good News of the Kingdom. It was the summer of 1980, between my junior and senior years in college, a school that proudly proclaimed as its motto, Christus primatum tenens, “That in all things He might have the preeminence.”

Yes, my college’s motto was essentially, “Christ the King.”

I’ve been thinking about this for a long time.

During Advent, The Cottage will host a paid subscriber special series — A BEAUTIFUL ADVENT — a thematic calendar from December 1 to Christmas. I offer these for the paid community in order to create a more intimate experience with a smaller community. I’m looking forward to it — lots of visuals and mini-reflections coming your way.

As a paid subscriber, you’ll receive invitations to Cottage Zoom gatherings, a monthly-newsy note about what’s going on behind the scenes, and other surprises throughout the year. I hope you’ll consider joining me “inside” the Cottage.

Just click the button below for information and to upgrade.

If you can’t afford a subscription but would like to join in for Advent, email us. No one is ever turned away for lack of funds.

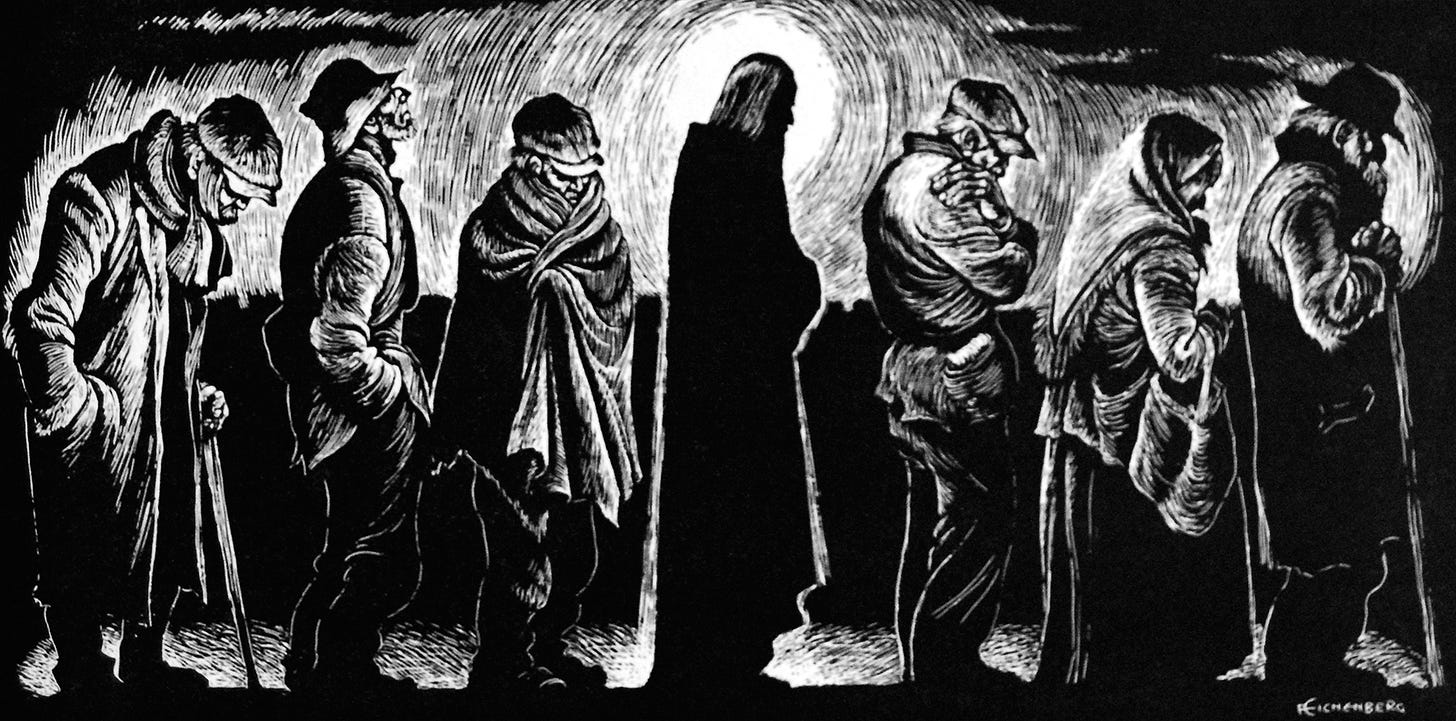

Matthew 25:31-46

Jesus said, “When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left.

Then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’

Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food, or thirsty and gave you something to drink? And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you, or naked and gave you clothing? And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?’

And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.’

Then he will say to those at his left hand, ‘You that are accursed, depart from me into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels; for I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not give me clothing, sick and in prison and you did not visit me.’

Then they also will answer, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or sick or in prison, and did not take care of you?’ Then he will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.’

And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.”

“The Mission and The Kingdom,” adapted from my book, Freeing Jesus

It is hard to explain to outsiders what it means when a young person in the evangelical world feels a call to become a missionary. Missionaries are to evangelicals as saints are to Catholics — heroes of faith.

Pictures of missionaries hung in classrooms and halls of evangelical churches, often accompanied by maps with pins pointing to the countries where they served. Great evangelical churches had big maps with lots of pins, showing the “reach” of the Good News from its pews to around the world; “Our Missionaries” read the sign above the maps. These were the people who left home and family to bring in the lost — and who traveled to all sorts of exotic places in the process. Surrendering to Jesus, giving one’s whole life to his lordship. It was a romantic and idealistic calling.

At least that’s how I thought of it at the time.

My friends at the evangelical college focused on two groups we thought most needed the gospel: secular humanists and Muslims. Europe, we fretted, had lost its faith and needed to reevangelized. And the great mass of Muslims, who lived in predominately Islamic-governed nations in Africa and the Middle East, had never heard the Good News because they were beyond the reach of conventional mission strategies. The more difficult it was to convert people, the greater the eternal reward.

Of the two choices, Europe sounded like a far better option to me.

I set myself to learning German, struggled with French, and spent one summer working with a mission agency in the Netherlands. The mission was called International Crusades, an awkward moniker in the days of the Iran hostage crisis. We mostly did door-to-door evangelism, passed out Bibles, and invited the skeptical Dutch back to church.

A few took Bibles, none came to worship, and most slammed doors in our faces. (Having doors slammed in one’s face is surprisingly good preparation for life, by the way.) We also ran a Bible school for little ones at a seaside resort, a strategy to get weary parents back to religion. No takers there either.

The long-term missionaries who hosted the student interns knew that we would not have much success with traditional evangelism. Thus, they hatched a plan to make us feel useful. The Dutch government sponsored workers to go into the homes of the elderly and disabled to do projects, such as cleaning, for those unable to manage on their own. The mission coordinator thought this was a great “opening” to serve and talk with homebound clients.

Sort of a captive audience for Jesus.

My first outing, where I was partnered with a male intern, was to the home of a disabled widower needing two things — his kitchen cleaned and windows repaired.

I got kitchen duty. Of course. I imagined that this work would be like the kind I had read about in a favorite devotional, Practicing the Presence of God, written by the medieval monk Brother Lawrence, who had found his Lord amid the washing up of pots and pans.

When I walked into the kitchen, however, I was sorely disappointed. There were no pots and pans. Instead, there was what looked to be a layer of grease and grime over all the counters, the floors, and the appliances — the scum seemed to date back decades, it was thick, sticky, smelly.

It was horrid.

The man, who was in a wheelchair, pointed me to a closet with a bucket, brushes, and bleach. I did not spend my time in holy contemplation. Instead, I scrubbed and scrubbed and scrubbed, desperately trying to uncover the surface of, well, anything. It was a gruesome archeological expedition. This was not what I imagined when I thought of being a missionary. I had envisioned people coming forward to accept Christ as their Savior, surrendering all to Jesus, and worshipping their sovereign Lord.

I could manage a few pots and pans like the cheerful Brother Lawrence, but not scraping grease from a kitchen that was at least twenty years older than I was.

The elderly man wheeled back into the kitchen while I worked. I wondered how I could witness to him. He spoke little English; I spoke little Dutch. Instead, he sat and watched, occasionally saying, Dank je wel, dank je wel. At one point, he pulled out a Bible and started reading it aloud. I could pick out a few words and phrases.

And so the hours went, me covered with grease and him reading to me. There developed an odd companionableness to it all, this harmony of work and words. The counters began to gleam; shoes no longer stuck to the floor. I wanted the room to shine, sparkling like a mansion in heaven. When I left a few hours later, he smiled and handed me some tulips in thanks.

I wrote about it in my journal, reflecting on a tension I felt. Yes, Jesus was Lord of the whole earth, the Jesus who reigned in my mission hopes — the One to whom all the people of the earth would bow, falling before God on the throne judging the nations. This was what my church preached and the hymns we sang proclaimed: the Lordship, Dominion, and Authority of the King.

Yet the most meaningful day of my mission seemed to have nothing to do with this glorious vision. Instead, it was grimy and inglorious, smelling of bleach and rancid grease, part of a socialist state-supported elder program. The only knees that had bent were my own, as I reached into filthy corners of that kitchen. What kind of kingdom was this?

I had not brought Jesus to anyone. Instead, my wheelchair-bound, elderly host had brought Jesus to me. His reading invited my heart to be cleansed along with the kitchen. There was something of me that got saved in the process, not the other way around.

None of this matched any theology of missions that I had studied. I could not tell anyone that I felt I had gotten somehow saved — at least more saved than before — through scrubbing floors. Nothing had to do with proclaiming Christ as Lord, extending his kingdom throughout the world, or worshipping the Lord in glory.

Jesus had shown up in this odd reversal of roles. I was the one who had been evangelized that day.

Whatever happened that day, it had more to do with the kindness found in a kitchen than cringing in a throne room.

* * * * *

Years later, I saw a thread on Twitter ridiculing theological terminology changing “kingdom” to “kin-dom.” The complaints called to mind when I first encountered a prayer using “kin-dom.” I remember worrying that it was a sort of watering down of the robust vision of Christ the King in glory, diminishing the power of his lordship.

Theologian Ada María Isasi-Díaz recalls originally hearing “kin-dom” from a Catholic sister. But to her it seemed a meaningful alternative to “kingdom,” a word fraught with colonial oppression and imperial violence. “Jesus,” she wrote, “used ‘kingdom of God’ to evoke . . . an alternative ‘order of things’” over and against the political context of the Roman Empire and its Caesar, the actual kingdom and king at the time.

“Kingdom” is a corrupted metaphor, one misused by the church throughout history to make itself into a political kingdom. Christians have often failed to recognize that “kingdom” was an inadequate way of speaking of God’s governance, not a call to set up their own empire. Isasi-Díaz argues that “kin-dom,” an image of la familia, the liberating family of God working together for love and justice, is a metaphor much closer to what Jesus intended.

If that sounds more like contemporary political correctness than biblical theology, it is worth noting that Isasi-Díaz’s “kin-dom” metaphor echoes an older understanding found in medieval theology in the work of Julian of Norwich.

Julian wrote of “our kinde Lord,” a poetic title, certainly, that summons images of a gentle Jesus. But it was not that. Rather, it was a radical phrase, for the word “kinde” in medieval English did not mean “nice” or “pleasant.” As theologian Janet Soskice explains:

In Middle English the words “kind” and “kin” were the same — to say that Christ is “our kinde Lord” is not to say that Christ is tender and gentle, although that may be implied, but to say that he is kin — our kind. This fact, and not emotional disposition, is the rock which is our salvation.

To say “our kinde Lord” was to say “our kin Lord.” Jesus the Lord is our kin. The kind Lord is kin to me, you, all of us — making us one. This is a subversive deconstruction of the image of kingdom and kings, replacing forever the pretensions and politics of earthly kingdoms with Jesus’s calling forth a kin-dom. King, kind, kin.

The kitchen in the Netherlands may well have been the closest I have ever been to the kingdom Jesus preached. There, the Spirit revealed the meaning of kin, of a “kingdom” with a “kinde Lord,” of simplicity, solidarity, and service.

That kin-dom — of the kitchen, of inverted parables, of alternative order, of the hungry, thirsty, sick, prisoners, and those with no place of safety or rest.

It would be a lesson I’d have to learn over and over again. With all our hopes of empire and power, is easy for western Christians to forget. We have rarely gotten it right.

Maybe we should change this day to Christ the Kinde Lord Sunday.

INSPIRATION

It’s a long way off but inside it

there are quite different things going on;

festivals at which the poor man

is king and the consumptive is

healed; mirrors in which the blind look

at themselves and love looks at them

back; and industry is for mending

the bent bones and the minds fractured

by life. It’s a long way off, but to get

there takes no time and admission

is free, if you will purge yourself

of desire, and present yourself with

your need only and the simple offering

of your faith, green as a leaf.

— R.S. Thomas, “The Kingdom”

We watch as the jets fly in

with the power people and

the money people,

the suits, the budgets, the billions.

We wonder about monetary policy

because we are among the haves,

and about generosity

because we care about the have-nots.

By slower modes we notice

Lazarus and the poor arriving from Africa,

and the beggars from Central Europe, and

the throng of environmentalists

with their vision of butterflies and oil

of flowers and tanks

of growing things and killing fields.

We wonder about peace and war,

about ecology and development,

about hope and entitlement.

We listen beyond jeering protesters and

soaring jets and

faintly we hear the mumbling of the crucified one,

something about

feeding the hungry

and giving drink to the thirsty,

about clothing the naked,

and noticing the prisoners,

more about the least and about holiness among them.

We are moved by the mumbles of the gospel,

even while we are tenured in our privilege.

We are half ready to join the choir of hope,

half afraid things might change,

and in a third half of our faith turning to you,

and your outpouring love

that works justice and

that binds us each and all to one another.

So we pray amidst jeering protesters

and soaring jets.

Come by here and make new,

even at some risk to our entitlements.

— Walter Brueggemann, “The Noise of Politics”

NOVEMBER GRATITUDE NUDGE

Have you ever experienced the “inverted” kingdom? Has God’s presence been known to you in surprising places and through unexpected people? Did gratitude play a role in that event or experience?

✨SOUTHERN LIGHTS: IN PERSON OR ONLINE✨

January 12 -14, 2024

Our theme is Reimagining Faith Beyond Patriarchy and Hierarchy — and many in the The Cottage community have signed up to gather in person!

Last January, almost 700 people gathered at St. Simon’s Island in Georgia for a packed weekend of poetry, theology, and music.

JOIN US THIS COMING JANUARY!

YOU ARE INVITED to join me and my dear friend Brian McLaren as we reimagine our faith beyond patriarchy and hierarchy in our interior lives, in our communities of faith, and in the Scriptures. We’ve asked three remarkable speakers to take us through this journey: Cole Arthur Riley, Simran Jeet Singh, and Elizabeth “Libbie” Schrader Polczer (our “resident” Mary Magdalene guide!). Our special guest chaplain for the weekend will be the Rev. Winnie Varghese (St. Luke’s Episcopal, Atlanta). And you’ll be treated to the amazing music of Ken Medema and Solveig Leithaug.

IN PERSON: Please come and be with us in Georgia. SEATS ARE INCREASINGLY LIMITED!

ONLINE: If you’d rather be with us virtually, you can choose that option. You will have access to the recordings after the event if you can’t attend live.

It helps in our planning if you sign up for the virtual option EARLIER rather than later.

INFORMATION AND REGISTRATION CAN BE FOUND HERE.

Why do you call me “Lord, Lord,” and do not do what I tell you?

I will show you what someone is like who comes to me, hears my words, and acts on them.

— Luke 6:46–47

I am a retired dietitian/nutritionist. For the last 10+ years of my 40+ career I worked in a variety of nursing. Sometimes I would fill in for a few days or few months. But I was long term at two facilities. Nursing home residents (and Sometimes their families) want to talk. Sure they want to complain about the meals. But, often, they just want to talk. Over time I came to realize that listening to the stories was likely more important than maintaining optimal nutrition.

Thank you for this. It was a welcome contrast to an event at my retirement community last evening. A group of well meaning women, from a variety of unidentified churches, brought us dinner, entertainment, and a strong conviction that God wanted them to share their faith with us. It was essentially a pitch for our souls. I left before dinner was served to visit with a neighbor who is worn out from the emotional and physical exhaustion of relocating her mother to assisted living.

I spent years studying in seminary and with text study groups, unpacking why this sort of testimony bothers me. Your article explains it beautiful. It’s not about knowing I’m saved. It’s about joining the clean up crew to make things better for others and this poor abused planet.

Who is “saved” is not my business. Who is in need is.