Discover more from The Cottage

Today’s post is the second in a series exploring fundamentalism from a variety of angles in light of the centennial of Harry Emerson Fosdick’s 1922 sermon, Shall the Fundamentalists Win? The first installment can be read HERE.

This essay is based on a suggestion I made in a panel discussion at the Wild Goose Festival in summer 2019. The other panelists were Brian McLaren, Frank Schaeffer, and Randall Balmer. In the conversation, it occurred to me that shame played a significant — but largely unnoticed — role in the development of American fundamentalism and evangelicalism, especially in regard to politics. Frank told me that I had to write on it, and I’ve not been able to stop thinking about it since.

Next week, the series will continue by looking at shifting definitions of “fundamentalist” and “evangelical.”

In the wake of the news that the Supreme Court is set to overturn Roe vs. Wade, Ashton Pittman of the Mississippi Free Press reposted a January 2022 article on the history of conservative evangelicals and abortion that included this quote from a letter by Christian Reconstructionist theologian Gary North:

The main reason why God has tolerated abortion without bringing judgment against societies that practice it is that abortion has been illegal in most societies. In the language of the pro-abortionists, abortion has generally been performed in back alleys. This is where abortion should be performed if they are performed. Back alleys are the perfect place for abortion. They are concealed. They are difficult to seek out, for both buyers of the service and as civil magistrates seeking to suppress them. They are unsafe places, placing murderous mothers under risk. Back alleys are where abortions belong.

Abortion is important in fundamentalist politics — and there is a lively argument among historians as to its significance in shaping the contemporary Religious Right. This essay, however, isn’t specifically about abortion or the news this week. It is, instead, about something embedded in this quote, the emotional framework — the psychology as it were — of fundamentalism: shame.

Notice how North uses shame. He believes that God “tolerated” abortion as long as it was wrapped in shame. In his view, shame — the humiliating concealment of sin — serves a useful purpose; it reminds society of the “sinfulness” associated with certain pregnancies (one thinks immediately of The Scarlet Letter) and the need to terminate them. In effect, “A”dulturous women who secure “A”bortions are so sinful that they can barely be mentioned in society — the entire business of unwelcome conceptions and “murderous mothers” is so dirty and disgusting that it belongs in “back alleys.” And that’s why God didn’t punish its practice. As long as abortion was clouded by disgrace and dishonor it might work to induce contrition and repentance. Society didn’t approve of it. Shaming abortion served a social purpose, even a theological one, to humiliate women to the point of surrendering to the church’s authority. But if something becomes legal its power to produce shame erodes and, along with it, so does the authority of shame-based religion.

Fundamentalists love to shame others — pointing out hidden sins of the heart, the “back alleys” of rejecting God, and risky rebellion against righteousness. Fundamentalists (and many of their evangelical kin) regularly employ a rhetoric of theological voyeurism to talk about sin. Shaming (with the implied threat of shunning) is often referred to as “conviction,” and is a public way (from the pulpit, in prayers, and through conversation) to describe reprehensible acts in even the most conservative churches to convince people of the hopelessness of sinful humanity without salvation.

Yes, fundamentalists are happy to shame. But they really hate being shamed.

That’s when they fight back. Hard.

* * * * *

Shall the Fundamentalists Win? was written in the early 1920s, a time when middle-class Americans prided themselves on being liberal and tolerant (how well this was practiced in reality is another matter, especially with regard to race). The Great War and pandemic created conditions that opened many up to new ideas, new technologies, and new possibilities for their own lives. People were moving to cities from small towns, more people were graduating from high school and attending college than ever, books and publishing and public libraries created a lively intellectual landscape, movies and radio transfixed and informed the populace, cars offered incredible mobility, and international travel became more widely available. America was rapidly becoming more cosmopolitan, more global, and more inclusive than it had been just decades before.

Churches struggled with the changes. A self-proclaimed party of “Fundamentalists” — they coined this term to describe themselves — defended the basics of gospel religion and fought back against a culture of “bobbed hair, bossy wives, and women preachers.” They worried that churches were succumbing to the spirit of modernism and they set themselves against other Christians — Harry Emerson Fosdick included — whom they considered heretics.

The opening salvo of Shall the Fundamentalists Win? included this shot: “The Fundamentalist program is essentially illiberal and intolerant.” This must have angered some fundamentalist leaders, many of whom had been educated in fine universities and considered themselves the theological and moral guardians of American democracy. To call someone illiberal and intolerant in the 1920s was a verbal shaming, akin to calling someone a racist or Nazi today.

Fosdick didn’t let up. Although his sermon carefully explicates Fundamentalist doctrines, it does so with more than a bit of mockery:

They would set up in Protestantism a doctrinal tribunal more rigid than the Pope’s…

You cannot fit the Lord Christ into that Fundamentalist mold…

Educated people are looking for their religion outside the churches…

Fundamentalists are giving us one of the worst exhibitions of bitter intolerance that the churches of this country have ever seen…

I do not even know in this congregation whether anybody has been tempted to be a Fundamentalist.

You get the point.

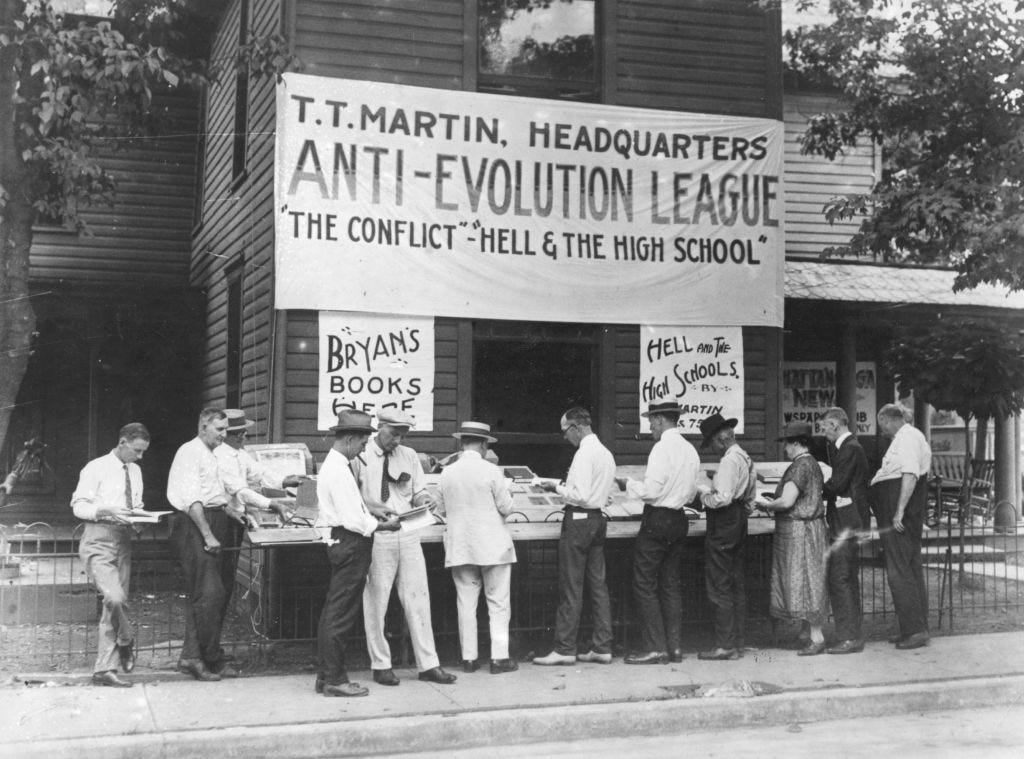

Fosdick’s analysis of Fundamentalist views of scripture and attitudes toward society were, in many ways, trenchant for the time. But the tone — no matter how warranted — modeled an approach elite culture leaders would adopt when writing about fundamentalism. Indeed, through the 1920s, Fundamentalists were depicted as backward, narrow-minded bumpkins. H.L. Mencken of the Baltimore Sun would describe fundamentalism at the Scopes trial as the “Tennessee buffoonery” of “inferior men,” mostly calling them backwoods ignoramuses.

These characterizations stuck. Later, they would be picked up by Hollywood and enshrined in films like Elmer Gantry and Inherit the Wind. Hypocritical anti-intellectual bigots from farms, small towns, and the South. Snake handlers and snake oil salesmen. Illiberal and intolerant. Fundamentalists were hicks.

This must have been especially difficult for some fundamentalists — people like William Jennings Bryan (politician, Secretary of State to President Wilson, and three-time presidential candidate) and J. Gresham Machen (faculty at Princeton and a leader in the Presbyterian Church) who graduated from Northwestern and Princeton respectively. Many early fundamentalist leaders understood themselves as upholding what Americans had always believed about the Bible and Christian practice and were most likely perplexed or shocked by the changes around them — and their sudden fall from public esteem. To go from respected leader to ridiculed buffoon, objects of derision and shame, must have been incredibly difficult. They never could believe that they were wrong because they were defending truth and traditional morality. Instead, they must have wondered if they had somehow failed as Christian pastors and leaders. That they had failed God.

Added to all of this was a basic theological assumption: human beings are utterly sinful from birth, always prone to evil, deserving of death and hell. The name-calling and public rejection mostly served to underscore what they feared to be true — they were worthless in God’s sight.

Being cast as hicks must have heightened their sense of failure, rubbing salt in wounds of hidden self-doubt, and perhaps turning it to self-loathing. This was a nearly a textbook laboratory for developing toxic shame. They couldn’t admit that their ideas might have been wrong. They certainly couldn’t embrace the insults of their critics. They created a kind of no-win situation for themselves.

In effect, the shaming reified their theology.

And it established a pattern still present in fundamentalism: alternating between withdrawal and anger. Indeed, the two most common symptoms of toxic shame are hiding and lashing out. In the last century, fundamentalists have vacillated between the two responses by either casting themselves as unprotected victims in retreat from a cruel world out to get them or projecting their ideas of sin and judgment onto the larger body politic with vengeance.

* * * * *

It isn’t new to suggest that fundamentalists preach a gospel of shame. Even if their critics have pointed that out, conservatives would be loathe to admit it. Indeed, in the years I spent in evangelical circles, I heard sermons about how “Eastern” religions were “bad” because they were based on shame and honor — and that Christianity was innately superior because it was about sin and guilt. But such sermons didn’t fool me and my friends as evangelical teenagers. We used to joke around by riffing on a popular fundamentalist pamphlet back in the 1970s: “God hates you and has a terrible plan for your life.” We should be ashamed. Not for what we did, but for who we are. Shame, shame, shame. They wanted us to feel it, to know its condemning power. Shaming saved.

Yes, they preached it. Fundamentalists used shame to control, manipulate, and enforce their authority. Anybody who has ever sat in a fundamentalist pew gets that. But it is provocative to suggest that American fundamentalism itself is a religion shaped by having been shamed. Unrecognized, unhealthy, and unhealed toxic shame created fundamentalism as we know it. An entire religious tradition defined by rejection, failure, and ridicule. Of being unable to confess that they were, indeed, wrong about science and doctrine and gender and race and a whole host of things. About being illiberal and intolerant. And being called on it.

But they just couldn’t admit they’d done anything wrong. Instead, they internalized that they weren’t worthy. And if they weren’t worthy, no one else was as well. At least they — God’s hicks — were trying to be faithful. So, they denied their secret shame and blamed their religious rivals for whatever went wrong in American Protestantism. Shame-bound groups always blame others as a way to assert superiority and exercise control. Blame the liberals. Those loose women. Those infidels. The shamed turned to shaming.

Those heretics. They are the problem. They aren’t even Christian. The heretics have dared leave the back alleys where they belong. They are destroying the church. They are America’s rot. Shame them. Blame them.

And, by externalizing shame and casting it on their enemies, fundamentalists become, in effect, shameless, a sense that fuels their own self-righteousness and permits them to bend (or break) the rules to accomplish whatever they believe to be God’s will.

And so, a century ago, the great divide of American Protestantism cracked open. Some people call it the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy. I’ve come to think of it as a internecine conflict between hicks and heretics, caught in a shame-bound family argument that wracked Protestant churches — and eventually reshaped American politics. We’re all caught in a cycle of shame and blame that started a century ago and seems impossible to break.

Please leave comments, share this post with others, or sign-up for a free subscription or upgrade to be a paid supporter at The Cottage. And remember to “like” the Cottage!

INSPIRATION

THE FUNDAMENTALISTS IN HEAVEN

discover they’re correct:

the mullahs, rabbis and the preachers,

the televangelists

complete with sundry

flocks and herds — the metaphors

have slipped through with them.

They’re wearing robes like Bedouins

from Bible illustrations.

The decor’s indistinct but still

a kind of middle eastern —

palm trees, minarets and fountains,

a Cecil B. de Mille affair. . . .

The end of all their expectation

is literal in evening light

where they must dwell at least forever

elbowing the saved.

— Geoff Page, read the entire poem HERE

AN INVITATION, in person or online:

Join me, Brian McLaren, Anthea Butler, and Kaitlin Curtice at Southern Lights on Memorial Day weekend for a multi-day gathering of progressive Christianity goodness! We’ve still got a few slots at the beach in St Simons Island, Georgia — or you can attend via livestream at home! (The recordings will be available for three months following the event to all registrants.) CLICK HERE for info and registration.

Congratulations to the winners of the May Day Freeing Jesus giveaway! Ten paid subscribers won copies of Freeing Jesus and one reader won the grand prize of a free registration to the online version of Southern Lights.

If you are one of those ten winners, please respond to the email we sent you so we can get you a copy of your book.

Subscribe to The Cottage

Part retreat, part think tank. A place for inspiration and ideas about culture, faith, and spirit.

Shame triggers Scapegoating, see Rene Girard, putting it on their enemies. Never works, only perpetuates toxic violence, We vs They.

Thank you for drawing attention to the shame-based Fundamentalist behavior. I am now wondering where, in Rabbi Friedman's system theory, the behavior of the elite folk fit. Those who used mockery and a trenchant tone - what drove that behavior? And how might they have addressed fundamentalism differently? This has obvious meaning for us today as we recognize the grievance-based behavior of White Christian Nationalists and wish not to throw gasoline on the fire, so to speak.