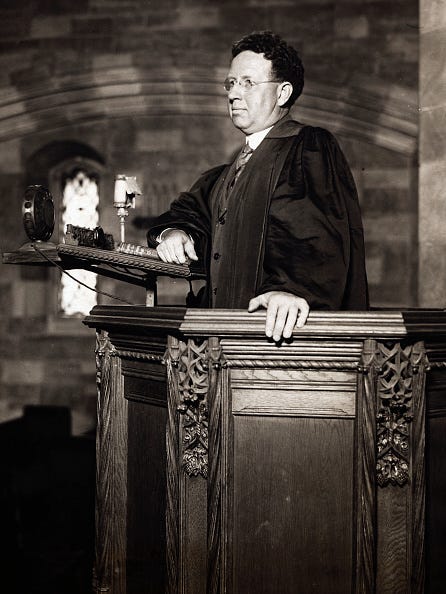

On May 21, 1922, Harry Emerson Fosdick preached one of the most important and influential sermons of the twentieth century: “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” In the sermon, Fosdick accused conservative Christians, who insisted on things like a literal virgin birth and biblical inerrancy, of being anti-intellectual and intolerant. Within weeks, the sermon went what we’d now call “viral” — being reprinted, discussed, and debated across North America. At issue was Fosdick’s central point: “Here in the Christian church today are these two groups, and the question the Fundamentalists have raised is this: shall one of them drive the other out?”

Conservatives went on to, at the very least, prove intolerance to be true. Within two years, fundamentalists forced Fosdick from his pulpit at New York’s First Presbyterian Church. However, Fosdick was fortunate enough to have a wealthy benefactor, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. who backed his cause and built the controversial pastor a glorious new liberal preaching cathedral — The Riverside Church in Morningside Heights.

One hundred years ago, the argument between Fundamentalists and Modernists raged in American denominations, at seminaries, in storied pulpits, and in small town churches. The fight destroyed careers, split venerable religious institutions, and played out in a dramatic trial in Tennessee. In the short term, moderate and liberal Protestants lost a few battles. But, by mid-century, they seemed to have won the theological war, as fundamentalists had largely retreated from public view. For about a generation, give or take a decade.

In the 1970s, fundamentalists would return from cultural exile and re-enter the public fray. They’d left over a huff regarding science and theology. And they returned with surprising confidence brandishing social issues and politics like a divine sword. They’ve never been quiet again, and they’ve never ceded a mite of public attention or political power. Indeed, since fundamentalists strode back into American cultural life, their liberal Protestant cousins were slowly but surely losing public influence — including their theological voice and political verve.

An odd thing happened along the way. Fundamentalism actually became bigger while exiled from America’s public consciousness. Despite the defeats of the 1920s on the home front (or perhaps because of them), conservatives took to the mission field and recruited new friends abroad — and found unlikely fellow travelers overseas. Perhaps no religious strategy ever worked more successfully than globalizing and politicizing a once-local theological tiff and turning it into an internationalist culture war.

In March 2022, one hundred years after Fosdick’s sermon, a group of Eastern Orthodox theologians wrote these words, essentially rehearsing “shall the fundamentalists win” regarding the war in Ukraine:

The support of many of the hierarchy of the Moscow Patriarchate for President Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine is rooted in a form of Orthodox ethno-phyletist religious fundamentalism, totalitarian in character, called Russkii mir or the Russian world, a false teaching which is attracting many in the Orthodox Church and has even been taken up by the Far Right and Catholic and Protestant fundamentalists.

From a the pulpit of a Presbyterian church in New York to the threat of nuclear war. It has been quite a century for fundamentalists.

It seems clear that modernists may have won a theological battle or two a hundred years ago but they lost the global war. With a century of hindsight, the answer to Fosdick’s question is startlingly simple. Shall the Fundamentalists win? They have.

* * * * *

Over the next month — the centennial of Fosdick’s sermon — I’m going to explore this hundred year history in mid-week posts here at The Cottage. My contention is that this old argument — one played out mostly between white men in elite institutions — was remarkably significant and changed the course of both American history and global religion. In effect, the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy is a long shadow hanging over the last century, and that we experience its continued influence every day in our churches and in our politics.

I invite you into this historical journey of rethinking fundamentalism past and future. And I hope you’ll add your perspectives and insights in comment threads. I hope you’ll bring others into this important conversation — a discussion a century in the making.

And to add to our conversation, I’m linking this lecture I recently gave at Washington State University’s Foley Institute in Pullman, Washington. (Note: the first three minutes of the lecture are missing — they consisted of me quoting from both Fosdick’s sermon and the Orthodox letter.)

INSPIRATION

On a roof in the Old City

laundry hanging in the late afternoon sunlight

the white sheet of a woman who is my enemy,

the towel of a man who is my enemy,

to wipe off the sweat of his brow.

In the sky of the Old City

a kite

At the other end of the string,

a child

I can't see

because of the wall.

We have put up many flags,

they have put up many flags.

To make us think that they're happy

To make them think that we're happy.

— Yehuda Amichai

AN INVITATION, in person or online:

Join me, Brian McLaren, Anthea Butler, and Kaitlin Curtice at Southern Lights on Memorial Day weekend for a multi-day gathering of progressive Christianity goodness! We’ve still got a few slots at the beach in St Simons Island, Georgia — or you can attend via livestream at home! (The recordings will be available for three months following the event to all registrants.) CLICK HERE for info and registration.

Grasping the historical context that lead us to where we are now empowers understanding and ideally prayerful compassionate participation. We each have our part in being the Body of Christ and participating in the breaking of the Kingdom of God. So grateful for your bringing your expertise to me and so many others. With appreication, inviting peace and strength!

I grew up in a fundamentalist church in the 1940s and 50s in Neenah Wisconsin. I heard from the pulpit that Harry Emerson Fosdick was opposed to the Bible as we were taught it.

Thanks for this history lesson. Look forward to hearing more about this controversy.

Today this church in Neenah, WI is called Calvary Bible Church and has a huge following.

I'm happy to have discovered the Episcopal Church, Trinity in Santa Barbara and Grace in Madison, Wisconsin. Thanks be to God!