Discover more from The Cottage

On Statues, History, Politics, and Division

Will future historians call our times the Second Great Iconoclastic Controversy?

This morning, my colleagues at PRRI issued a brand new report, Creating More Inclusive Public Spaces, a two-year follow up to their 2022 survey on the removal of Confederate statues across the United States.

The survey shows that understanding and marking the history of the Civil War remains a significant point of division politically, racially, and generationally in American public life .

I’ve been thinking about statues for a few years and the centrality of history to the current tensions in western cultures. And guess what? One of the most ancient conflict in Christianity is replaying itself in our secular societies.

My essay begins below the photo.

Several times a week, I drive through an intersection where a statue was once located. It is empty space now, a barely visible circle in the road, where a Confederate soldier had stood in Alexandria, Virginia, the boyhood home of Robert E. Lee.

Since 1889, a decade after Reconstruction failed, this lone warrior defiantly faced southward, his back turned on Washington, D.C. He gazed down on passers-by with a look of dispirited contempt that seemed to mock both Black citizens and the city’s new Yankee occupants.

My family nicknamed him the “dejected Confederate.”

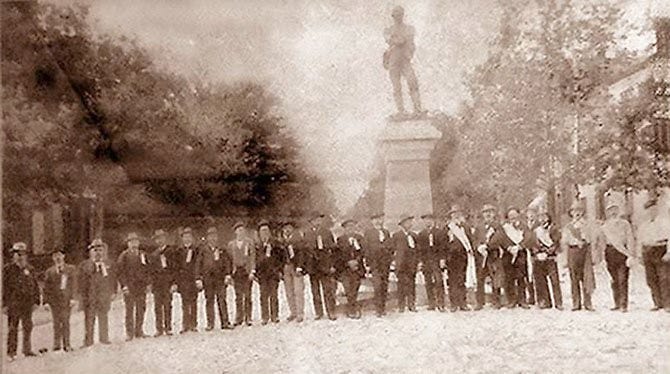

The statue’s real name was Appomattox. It was one of the earliest statues to glorify the south’s lost cause; it honored Alexandria’s war dead and was erected by the United Confederate Veterans.

Its purpose proclaimed by an inscription on the base: They died in the consciousness of duty faithfully performed. In one of city’s largest 19th century public gatherings, throngs of citizens cheered its dedication – an event that featured speeches by Virginia’s governor and the nephew of General Lee.

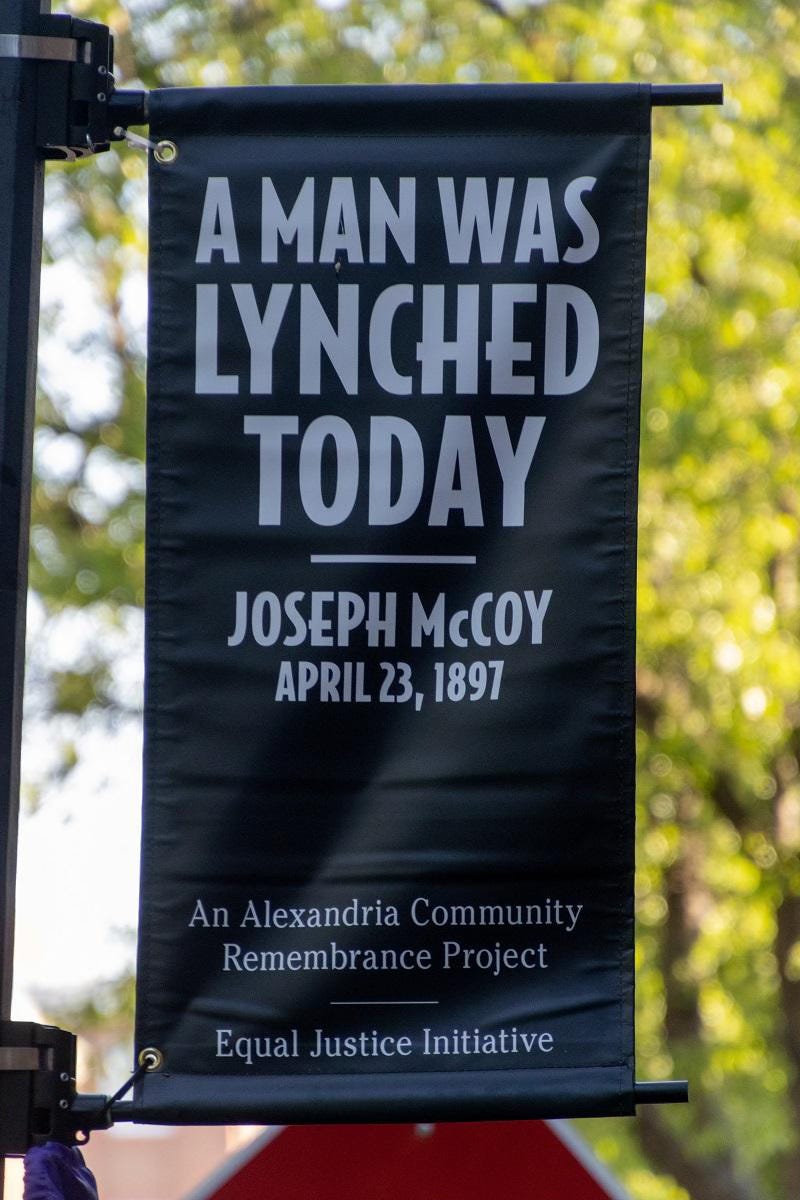

These were the first years of Jim Crow. I often wondered if any of those who celebrated the statue would be among the thousand-person mob who, just a few years later, jeered and hooted when Joseph McCoy was lynched on a lamppost just blocks away.

For decades, Appomattox proved a popular tourist attraction, its image depicted and shared on tens of thousands of postcards. Once cameras were readily available, it became a spot where visitors proudly posed. But those who erected the sullen soldier also suspected that it might become a controversial statue, perhaps even a political target. Six months after its dedication, the United Confederate Veterans convinced the Virginia House of Delegates to protect the statue against alternation or removal in perpetuity.

He’s gone now, after much argument and several changes to the law. In June 2020, a month before the city was set to remove the statue, the United Daughters of the Confederacy did the deed themselves and then secreted him off to an undisclosed location. For several months, his pedestal remained, like an ancient monolith from some forgotten civilization. But that was taken down as well. The city paved over the foundation so cars could move freely through the intersection. Nothing remains of the dejected Confederate.

* * * * * * *

Appomattox is only one of the many memorials removed in recent years from public spaces in Virginia. The fight to take down the Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville resulted in neo-Nazis and white supremacists invading the university town and ended in murder. Weeks of dramatic protests in Richmond, Virginia’s capital and once the capital of the Confederacy itself, led to the dismantling of the many statues that once constituted Monument Avenue, a wide boulevard of multiple circles with memorials dedicated to the leaders of the defeated southern army.

Not long after the Richmond bronzes and marbles had been removed, I was in the city speaking at a church. The pastor, a religious leader who agreed with their removal, asked me: “Have you driven down Monument Avenue yet?”

“No,” I replied, “I’ve haven’t been there recently.”

“It is stark, emotionally powerful in a different way,” he said. “You look down the road and the statues are all gone. There are empty altars everywhere.”

Empty altars everywhere.

As soon as he said it, I understood. These were not just statues. They were idols, icons, perhaps even “saints.” We may be talking about history or inclusion or diversity and fairness, but accompanying all our arguments is a sense of something else, something ineffable, a very sense of something religious. These were altars – shrines – to a kind of civil faith, an American mythology of identity and meaning, of the triumphs of the ancestors. Standing high on their pedestals, they had marked the land as sacred, turning cityscapes into outdoor temples.

It is not just Virginia or the American south. But statues are coming down all over America – Father Serra in California, the Soldiers Monument in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Christopher Columbus in Minneapolis. Indeed, it is not just the United States. They are coming down in many communities around the world as new generations try to come to terms with injustices and failures of the past.

For some people, however, monuments are markers of familiarity – like an old church on Main Street, a building you walked by for years without thinking about it very much. You may never have worshipped there, or never even walked in the door. But, one day, cranes and bulldozers arrive to raise it to make way for new condominiums – or a fast-food joint. You may feel a tinge of sadness, maybe a bit angry at “progress.”

If you were a member, however, you probably feel a devastating sense of loss. No matter how sensible the decision to sell the church building, its ending marks an ending for you. Perhaps your parents were married there; you and your children baptized there. Even those most sympathetic to the change feel a sort of grief. That loss is often entwined with a sense of disorientation and dislocation. You might feel a bit afraid. Who will remember what happened within those walls?

But this isn’t just about emptying church buildings. It is about history – the stories that shaped our understanding of the past, artifacts and places once considered sacred, and those formerly deemed as heroes, perhaps even cultural “saints.”

What goes up where something has been taken down? What stories will we tell those who comes after us? Who will serve as our models, mentors, and guides to the future?

Empty altars everywhere.

* * * * * * *

Ultimately, those empty altars are about history. Protesters do not want monuments to injustice, enslavement, and colonization in public spaces any longer, especially as younger generations strive to become more diverse and inclusive. They insist that past historical failures should not be lionized in relation to a wider democratic project.

But protectors also appeal to history against the protesters: “You’re just trying to change history!” is the most typical accusation – often followed by, “Don’t dare take away our heritage.”

I’ve been interested in history my entire life. When I first learned to read, my mother would take me to the library and I’d check out books on ancient Rome, archeology in Mexico, and American history. Eventually, I majored in history in college and earned graduate degrees in the history of Christianity. I’ve taught history in religion departments, in history programs, and at seminaries. I’ve lectured about history and written books steeped in history. On radio shows, television interviews, and podcasts, hosts quiz me about historical parallels to contemporary events and ask me to speculate on how the past will shape the future.

I’ve also been a Christian my entire life, something that is increasingly odd in the United States. Although I have changed denominations a couple of times, and my theological opinions have broadened, deepened, and grown more inclusive over the years, I’ve questioned and doubted and gotten angry but stayed put – my soul’s taproots nourished by its wellspring of faith.

The more I think about it, the more I am convinced that being a historian has enabled me to stay Christian. In graduate school, we argued whether history was a social science or whether it was part of the humanities. We fought about classical methods, postmodern interpretations, and the nature of the past. We learned to ask hard questions, see the world from different points of view, treasure texts and odd objects, and even hold onto stubborn, old-fashioned things called facts.

History is a rigorous discipline if, of course, you engage it honestly. But it also involves some faith as well, a tentative trust that we frail humans can understand and know why other frail humans – those who lived long ago – made the choices they did and how their actions both created and reflected the worlds in which they lived.

This, history has become a spiritual practice for me, mostly because it presents the same paradox as does life: it never changes and yet it changes all the time.

There’s a sort of chastened realism in history, even the most ideologically committed partisan usually admits that some events happened. History never changes in that it presents certain facts about past events in human experience: George Washington was the first president of the United States; from 1861-1865, America fought a civil war; 6 million Jews died in Europe during World War II.

If you deny any of these things, you are flat wrong about events of the past. Historians can prove you wrong. We can dig up George Washington’s body and prove his identity through DNA, legal and military records prove that a civil war happened, and there were thousands and thousands of witnesses and survivors to the Holocaust. Some people refuse to believe these things happened. However, if you do, you are likely to find yourself labeled a conspiracy theorist – or worse. If you lie about the past – even on X (Twitter) – some historian will call you out. And you’d deserve it.

Strange things do happen with facts, however. Generations of Protestants believed that on October 31, 1517, Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to a church door in Wittenberg to start the Reformation. But the best historians insist this never happened – and the story was most likely invented decades later. In graduate school, one of my professors kept a list of “Things You Thought Happened in History but Did Not.” There were a lot of things on the list. But that’s what historians do – sort out what really happened from what might have happened and what absolutely did not happen.

However, history always changes as well in that we – people in the present, including historians – reinterpret the meaning of those past events in relation to our lives now. George Washington lived, yes. But what does his life mean for us? The Civil War happened — is something like it happening again? And there was a Holocaust. How does that event impact what’s happening in Israel and Gaza right now?

Two things are true about public monuments – 1) they represent events that happened (for the most part), and 2) they reveal how the generation who erected them interpreted those events.

But those statues can’t insist how we continue to understand them in successive decades.

History isn’t static. It always demands reinvestigation, reinterpretation, and reinterrogation.

The fight over public monuments is about history – and it is about faith in what is true and how we make meaning.

* * * * * * *

Those empty altars witness to a cultural reality: We live in an iconoclastic age.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines iconoclasm as “the action of attacking or assertively rejecting cherished beliefs and institutions or established values and practices” and “the rejection or destruction of religious images.” Iconoclasm is political and religious. They smash idols of history and destroy images of saints.

Iconoclasts take down those things which their ancestors valued and venerated because they reject ideals and heroes of a particular conceptions of the past, now deemed offensive to a new generation. Iconoclasm is about how history, identity, and memory mark the landscapes of our lives and communities; and what happens when inherited forms of politics and religion fail.

There is nothing new about idol smashing. Following the death of the tyrannical emperor Domitian in 96 CE, Pliny the Younger wrote of gleeful iconoclasts erasing his memory:

It was our delight to dash those proud faces to the ground, to smite them with the sword and savage them with the axe as if blood and agony could follow from every blow. Our transports of joy – so long deferred – were unrestrained; all sought a form of vengeance in beholding those bodies mutilated, limbs hacked in pieces, and finally that baleful, fearsome visage cast into fire, to be melted down, so that from such menacing terror something for man’s use and enjoyment should rise out of the flames.

(Pliny the Younger, Panegyricus 52)

For most of human history, political events – such as war or the fall of a dictator – have occasioned destruction of statues and images of losing regimes. Museums across the globe display regal visages with missing noses or disfigured faces, imperial figures with body parts lopped off, and effigies of the powerful defaced. Time was not the only enemy of these ancient works.

Recent examples come to mind as well — like Iraqis (with the assistance of United States soldiers) felling Saddam Hussein’s statue or the Libyan rebels who detached Muammar Gaddafi's head from his bronze figure and turned it into a soccer ball.

Religious movements are often iconoclastic. Indeed, Christianity has always had an iconoclastic tendency. Since 300 C.E. or so, Christians have ripped down statues — images they considered morally corrupt or theologically suspect. The heroes and saints glorified in stone put up by one generation were often targeted by their own grandchildren or great-grandchildren who came to believe that the old ways needed reform — and gleefully stripped the altars of church and state to make way for a new thing.

The United States, was founded, at least in part, by iconoclasts — the Puritans. Their theological platform included stripping altars in parish churches. No more statues of saints, decoration, or even stained glass windows.

Ever since the Richmond pastor uttered those words, “There are empty altars everywhere,” I’ve not been able to get them out of my mind. I’ve thought a great deal about the history of iconoclasm — and how so many renewals and reforms begin with taking down statues and emptied altars. One can’t be a Protestant, for example, without having at least a bit of sympathy for iconoclasts. None of our churches would even exist without this strangely human impulse to clear the sacred decks of that which clutters the soul — and the landscape around us.

We may be inveterate iconoclasts, but it is equally true that humans are equally inveterate statue builders. Altars don’t stay empty very long. Public spaces are rarely vacant of meaning – something will fill them.

The question is what will come to occupy the empty space? And how will we decide?

I’m a historian, not a soothsayer. I have no idea what’s ahead. And yet, I do know that this argument is central to current politics across the western world. We might not say it clearly, but we are fighting over statues.

Perhaps future historians will call our times The Second Great Iconoclastic Controversy.

INSPIRATION

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

— Percy Bysshe Shelley

These statues are not just stone and metal. They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.

― Mitch Landrieu, former Mayor of New Orleans

Don’t forget to sign up for the newsletter digest, The Convocation, that I’m co-authoring with Robert P. Jones, Kristin Du Mez, and Jemar Tisby. It is free and comes out every Thursday.

You can get all our best writing on religion and politics in one place — and our new twice-monthly podcast, The Convocation Unscripted.

The most recent episode is linked below — and it’s a good one!

In the past I used to turn discussions with folks defending Confederate statues by moving the conversation from slavery to treason against our country. This almost always was convincing. I am not so sure this argument would work anymore.

Related, but not the same, early Christians made a mission of destroying Greek and Roman temples. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have those place still for study? Again, no correlation to memorializing slavery and Jim Crow, but oh the thought of the Library at Alexandria not having been destroyed…

A beautiful essay.

There are so many ways to go - Why mainline churches are shrinking? Because they won't let go of their icons, as the culture and younger generations honor them no longer. Trumps's MAGA - the profound sense of loss that many feel as they look at where the "statues" used to be. Whether physical statues or local buildings, or even webs of relationships.

What "liberal" Christians offer in their place is a form of demotion. From being part of a dominant group, to just one of the masses. As a "liberal" we have to do better. I wish I knew how. Somehow, being a child of God, beloved even though flawed, does not seem to be enough.