Discover more from The Cottage

In a Zoom webinar this week, Robert Jones of Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) and I were discussing religion and politics. When I made a point about the decline of white evangelicalism in recent years, Jones had statistics at the ready: “Did you know that that both white evangelicals and white mainline Protestants make up the same percentage — 15% — of the American population?”

Although I knew that white evangelicalism was declining, I was not aware that white mainline church affiliation had ticked up slightly. With the evangelical drop-off and the modest mainline increase, the two historic white Protestant families — conservative and liberal — who were the dominant majority of American religion as recently as 1960 — are now essentially tied together sharing the religious adherence of less than one third of the nation’s population.

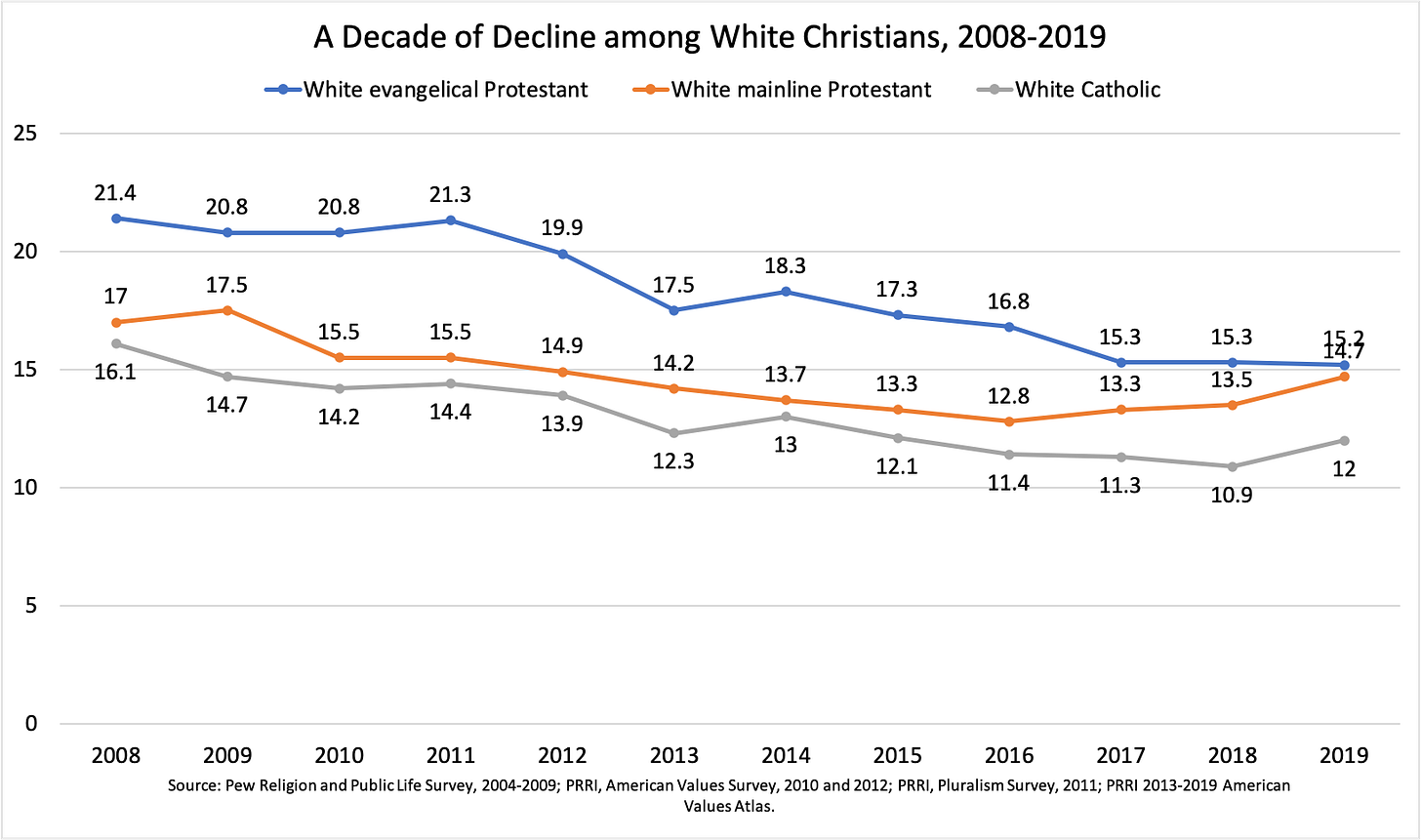

To support his assertion, Jones sent me this chart from a larger study PRRI will release next week:

The chart covers a decade of data based on a number of studies from both Pew and PRRI. This particular graph shows the declining percentage of white Christians in the three major groupings of (1) white evangelical Protestants (generally those who are theologically conservative and members of groups like the Southern Baptist Convention, the Assemblies of God, or non-denominational churches), (2) white mainline Protestants (generally more theologically centrist or liberal and members of churches with European roots such as Episcopalians, Lutherans, Presbyterians, and Methodists), and (3) white Catholics. The percentage of white Christian decline reflects an overall decrease in the white population of the United States (from approximately 64% of “white alone - non-Hispanic” in 2009 to 60% of the same in 2019).

The numbers are interesting, but they also suggest some important trends in American religion that matter for both churches and national politics.

FIRST, the percentage decline of white evangelicals has outpaced the demographic decrease of whites more generally. Their 6.2 point decade decline exceeds the roughly 4 point decline in the overall white population in the same period — so their religious decline is not merely one of racial demographics. Compare that to the white mainline (2.3 point decline) and white Catholic (4.1 point decline) percentages, each of which is more in line with the shrinking pool of whites in the overall population. This suggests that some number of white evangelicals are actually leaving their churches, marking a purposeful and noticeable decline in evangelical adherence in the last decade.

The overall percentage of evangelicals in the United States is a bit difficult to measure, as it depends on sometimes conflicting theological and sociological definitions. But the best estimate is that the total number is somewhere between 20-25% of the American population, a figure that demonstrates that evangelicals of color — Hispanic, Asian, and black — are increasingly the most stable (and growing) part of any evangelical coalition. Yet, at the same time, the evangelical community is increasingly fractured by divisions based on race, politics, and culture.

The decline of white evangelicalism and the divides within racially diverse evangelicalism work to undermine a widely-held bit of conventional analysis regarding American religion. In 1972, Dean Kelley, who worked for the liberal National Council of Churches, wrote a book entitled Why Conservative Churches Are Growing. Although the book was more nuanced than the title suggests, the title itself became a truism in some church circles — that only conservative churches could grow. In the nearly fifty years since its publication, conservative think-tanks and right-wing critics have bludgeoned liberal Christians with the idea that progressive theology and a commitment to social justice led to mainline decline — and would be the death of their churches. The trends of the last decade, however, upend that thesis. Of all white Christian groups, the most theologically liberal one — white mainline Protestants — has shown the smallest decrease, even while their denominations adopted openly progressive social policies including marriage equality and full inclusion of women and LGBTQ persons in their churches. Indeed, white mainline decline modestly matches the overall decline of America’s white population.

SECOND, while it cannot be proved by the data on this chart, it is suggestive that there is a noticeable drop in white evangelicalism from 2016 to 2017. This numerical drop parallels anecdotal evidence that those white evangelicals who felt distressed or concerned by the election of Donald Trump — and the overwhelming support of Trump by the larger white evangelical community — have been leaving their churches. The “Trump effect” in white evangelicalism does not necessarily hold for black, Asian, or Hispanic evangelicals, who tend to vote more in line with non-evangelicals in their communities than they do with their white co-religionists. Thus, white evangelicalism is suffering both the loss of their own political dissenters and from public political disagreement with their brothers and sisters of color. Neither of these things bodes well for the future of American evangelicalism.

THIRD, all of this pales in comparison to the largest trend in American religion: the shift toward religious disaffiliation. While white mainliners may breathe a bit easier with a slight four-year uptick in their numbers, there is no denying the power of the growing communities of non-religious, humanist, spiritual-but-not-religious, and secular Americans. Although not on this particular chart, the same decade reveals an increase of religiously unaffiliated people from 16% of the population in 2008 to a whopping 24% in 2019. Religiously unaffiliated persons now constitute the largest “religious” group in the United States. For decades, sociologists of religion insisted that the United States was exceptional in its religiosity among developed and wealthy nations — but that exceptionalism is now eroding as America increasingly resembles Canada, Australia, and other western European nations in religious composition. It is important to note that “religiously unaffiliated” is itself a diverse category — including a large number of young adults, people from every racial and ethnic group, and a complex diversity of atheists, agnostics, the a-religious and post-religious, the multi-religious, and those dissatisfied with conventional religious choices.

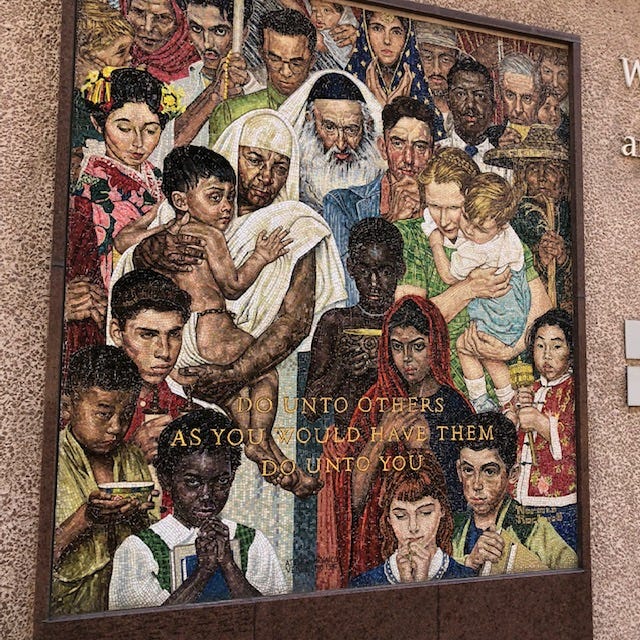

(photo: Thanksgiving Square, Dallas, TX, taken by Diana Butler Bass)

FINALLY, the upshot of this is that nothing in American religion is as it was. If you are a white person hankering for the religious nostalgia of your youth, you are out of luck. While the United States has long been a nation marked by its white steeples, new religious and non-religious architectures now arise in our communities, and that is transforming our politics and our future. The new needn’t take down the old, because what has been can exist — and potentially thrive — in the new environment. But the future of white Christianity in America depends on its capacity to change, to redress its long history of privilege, to welcome the new, and to be comfortable as one guest among many at the nation’s expanded table.

We need a new story of American faith — what it means to be a citizen, to love the land we inhabit together, and to treat one another with grace and dignity.

INSPIRATION:

There was a time I would reject those

who were not my faith.

But now, my heart has grown capable

of taking on all forms.

It is a pasture for gazelles,

An abbey for monks.

A table for the Torah.

Kaaba for the pilgrim.

My religion is love.

Whichever the route love’s caravan shall take,

That shall be the path of my faith.

—Ibn Arabi

White Christianity has been many things for America. But whatever else it has been -- and the country is indebted to it for a good many things--it has also been the primary institution legitimizing and propagating white power and dominance.

― Robert P. Jones

American Christianity has betrayed the religion of Jesus almost beyond redemption. Churches have been established for the underprivileged, the weak, the poor on the theory they prefer to be among themselves. Churches have been established for the Chinese, the Japanese, the Korean, the Mexican, the Filipino, the Italian and the Negro with the same theory in mind. The result is that in the one place in which normal, free contacts might be most naturally established - in which the relations of the individual to his God should take priority over conditions of class, race, power, status, wealth or the like – this place is one of the chief instruments for guaranteeing barriers.

—Howard Thurman

The whole message of the Christian scripture is based in the idea of metanoia, the change of heart that happens when we meet God face-to-face. Even a cursory knowledge of history reveals that Christianity is a religion about change. The Christian faith always changes--even when some of its adherents claim that it does not.

― Diana Butler Bass

God’s not nonexistent; He’s just been waylaid

by a host of what no one could’ve foreseen.

—Jacqueline Osherow

SOME PODCASTS OF INTEREST:

Tripp Fuller of the Homebrewed Christianity Podcast and I have been talking religion and politics in the news — and hosting great guests — every week in a series we call Ruining Dinner, an election season pop-up community of learning and solidarity. You are invited to join in! Please click here for more information.

You can listen in to me and Robert Jones on the first episode in a new webinar series -- Justice, Love, and Humility: Pastoring a Divided Culture. We talk about how our country arrived to this point of tribalism and division, and we’ll discuss how churches can provide hope – and not more division – to their communities. Register at: https://amplifymedia.com/justice-love-and-humility/how-did-we-get-here/

For this retired UCC pastor your closing line "we need a new story" absolutely sums up where we are in the mainline church. More than worship styles, or where we are on social justice issues, or how we run our stewardship campaigns, we need a narrative, a story that taps into the deep spiritual hunger in our land. I am even wondering if the Biblical story is still the old wine skin that can hold the new wine--of whatever that new narrative might be. Metaphysics is not irrelevant at all. We need a vision, a narrative that is both irresistible AND is true: it adequately encompasses all of reality, including science, our humanity, and all of creation. By irresistible and compelling I mean the narrative is strong enough to rally the folks, to build the beloved community.

I am definitely sharing this with colleagues. Thank you for the analysis and for the inspirational quotes. I especially like the quote you picked by the theologian Diana Butler Bass. Seriously.