Every week, I get letters and emails saying, “I don’t understand how Christians, especially evangelicals, can support Donald Trump. I don’t understand any of this.”

The notes are often tragic — someone was shunned by other churchgoers for being a Democrat, a person questions politics preached from a pulpit and is marginalized by the pastor, or a member slinks away distressed because his friends choose MAGA over the gospel. Often, it is deeply personal — the parents of a gay teen who leave when people in their church joke about or make threats regarding LGBTQ people, a minister who preaches an upsetting sermon gets fired, or someone whose spiritual journey raises issues about justice is ridiculed or disciplined by their community.

The letter writers tell me how alone they feel. They were abused or rejected by churches — communities that they once served and loved and supported — because they tried to follow Jesus more honestly and deeply.

Usually their experiences lead them to reading books — lots of books — to help understand what happened to them. Nearly everyone tells me that they turned to historians to help them make sense of it all — often mentioning Kristin Kobes Du Mez’s book, Jesus and John Wayne, or Heather Cox Richardson’s daily post, “Letters from an American.”

Historians help. (As a historian, that makes me both proud and happy!)

But, even after coming to terms with historical developments and contexts, with facts and patterns, some insight or explanation still seems unformed and elusive. One can read — or write — history and still puzzle, “I don’t understand.”

There’s been a lot of “I don’t understand” in recent years. And this primary election season is particularly bad. The day after the New Hampshire primary people — even pundits on cable who are paid to convince you that they understand — said “I don’t understand.”

I’ve got a freakin’ Ph.D. in American religious history and I still say it: I don’t understand.

That’s because human choices and the motivations of the heart are really, truly hard to understand. Sure, you can live at a particular time and in a particular culture that will shape the likelihood of how you’ll act. But human beings are really slippery fish when it comes to what makes sense, following patterns, or doing what you think they will do. Historians know this. People — in the past and now — don’t always act according to plan. A colleague of mine used to quip: The neatness of theory is no match for the mess of reality.

I’ve got a freakin’ Ph.D. in American religious history and I still say it:

I don’t understand.

Those much-ridiculed “man-in-a-diner” articles can actually help on this score. When an enterprising reporter tries to figure out why some ordinary Joe in Peoria votes for someone he’d never let his daughter date or for the rich tycoon trying to stay out of jail proclaiming his undying love for the little, uneducated people.

In the “man-in-a-diner” genre, this piece from Politico is one of the best I’ve ever read. It appeared the day before the New Hampshire primary. It tells the story of Ted Johnson, a 58 year old retired Army officer, and the opening graphs say it all:

BEDFORD, N.H. — “This,” Ted Johnson told me, “is what I hope.” We were here the other day at a bar not far from his house, and we were talking about Donald Trump and the possibility he could be the president again by this time next year. “He breaks the system,” he said, “he exposes the deep state, and it’s going to be a miserable four years for everybody.”

“For everybody?” I said.

“Everybody.”

“For you?”

“I think his policies are going to be good,” he said, “but it’s going to be hard to watch this happen to our country. He’s going to pull it apart….”

“He’s a wrecking ball,” Johnson told me here at the place he chose called the Copper Door.

“Everybody’s going to say, ‘Trump is divisive,’” he said, “and he’s going to split the country in half.” He looked at me. “We got it,” he said.

It’s what the Ted Johnsons want. . .

“Our system needs to be broken,” Johnson had concluded, “and he is the man to do it.”

And that’s when I understood.

At least I saw something I hadn’t seen before.

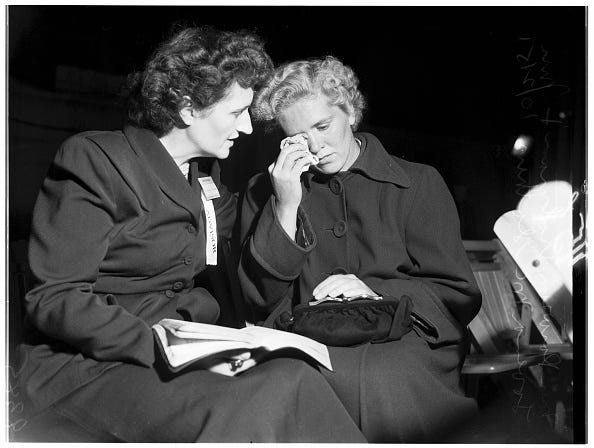

The article isn’t about religion. There’s no mention of Ted’s church or faith. There is a patriotic cross in a photograph accompanying the story, but no explanation of its prominent place on a display shelf. We don’t know if Ted is a Protestant or Catholic or none of the above.

In some ways, his personal faith doesn’t matter.

What I suddenly recognized is that once I too wanted everything to be broken, everyone to be miserable. When I became an evangelical. You know evangelicals — especially white ones — the religious people who love Donald Trump, stick with him no matter what, and vote for him in massive numbers. They also love making people miserable. Indeed, it is a central tenet of evangelical faith, the entry ritual into community.

In evangelicalism, the first step to salvation is making you miserable. Sermons point out your misery, your sad state of existence, the hopelessness of the human condition. If you aren’t an evangelical and seem happy, your evangelical friends are convinced you are pretending, hiding something, are in denial, or are deluded by Satan. If you ever reveal a doubt or sorrow, they are waiting to pounce — to point out your misery and remedy it through conversion. You must see that you have led a miserable life, made miserable choices, are a deeply miserable person. Misery is the doorway to being saved.

The core of evangelicalism is theological — it reveals a deep, inescapable human problem (we are locked in misery by sin) and salvation from the problem (surrender to Jesus through conversion). The only real happiness is eternal life, the heavenly realm. You cannot be happy or go to heaven without profound sorrow over the misery of your soul. You must be broken before you can be saved. Only a strong Savior can fix you. And, once you have experienced this, you have to tell everyone. Point out all the brokenness, bleakness, corruption, and carnage. Yes, soul carnage. That’s our true state. American carnage. Global carnage.

I’ve heard that sermon a thousand times. Carnage is hope. Brokenness is healing. Blood dripping from the cross, flowing in the streets, saves.

Misery means more people in heaven.

Pundits, historians, journalists — all of them recognize that Trumpism is essentially religious. But religion is more than a set of predictable voting patterns or boxes on a survey. It is a deeply held vision of the world, a shaping narrative in the soul. And this one is utterly clear and simple. No mystery really. To be broken — and to break things — is what comes first. It is the core of American evangelicalism — "You must be born again" — the ritual, the sawdust trail, the mourning bench — translated and encoded into a political movement, a political party, and American nationalism.

You can blame evangelical support for Trump on racism or misogyny. You can come up with a smart, historically informed analysis that makes sense. Those books help. But, ultimately, it is hard to understand because it is about something more subtle, more pervasive, less graspable. It is an orientation, a whisper in the wind, a stern minister explaining how God predestines millions to eternal torment, a half-buried memory of your grandmother singing a blood-soaked hymn over your crib.

What can wash away my sin?

Nothing but the Blood of Jesus

What can make me whole again?

Nothing but the Blood of Jesus.

O precious is the flow

That makes me white as snow

No other fount I know

Nothing but the Blood of Jesus

Nothing but the Blood of Jesus.

Like it or not — believe it or not — white evangelicalism is a uniquely American folk religion that has shaped our entire history, culture, and political life over the last three centuries. It is just there, in this Christ-haunted nation, like humid air hanging over the Mississippi delta in the summer. We breathe it, whether we recognize its existence or not. Whether we acknowledge it or not. And it took its most unique shape in the American South, where it remains, even in these supposedly secular days, a potent force.

Flannery O’Connor was right:

…in the South the general conception of man is still, in the main, theological. That is a large statement, and it is dangerous to make it, for almost anything you say about Southern belief can be denied in the next breath with equal propriety. But approaching the subject from the standpoint of the writer, I think it is safe to say that while the South is hardly Christ-centered, it is most certainly Christ-haunted. The Southerner, who isn't convinced of it, is very much afraid that he may have been formed in the image and likeness of God. Ghosts can be very fierce and instructive. They cast strange shadows.

A few years ago, Heather Cox Richardson wrote a book titled, How the South Won the Civil War. That was also the book’s thesis — that the South actually won the Civil War. It is about politics and history, of course. It touches on religion, too.

It is a great book. One of the best history explantations of these days. In the years since, it has compelled me to consider the extent of the “southernization” of American religion. The South not only won many of the political and cultural battles following the Civil War, but it also won the theological and spiritual ones. Despite a brief set-back in the 1920s, white evangelicalism of the southern sort has done little else but strengthen its grip on America. The evangelical revival of the 1970s, its politicization in the 1980s, its crystalizing fundamentalist theology in the 1990s, and its wider cultural acceptance in the early aughts (along with its corresponding “murder” of liberal churches — what’s a little breaking when it comes to denominations?) and taking over all of American Protestantism (perhaps even American Christianity as well).

We’re all the South now. Even in a culture where people are turning their back on Christianity and fleeing church (she remarks ironically: Maybe these two things are related?).

There’s no escaping it. We all live in the tormented and ghostly shadow of a bloody, misery-laden story drawn from a particular interpretation of the Bible, reified by generations of prayers and sermons and songs. Now enshrined in politics. The road to heaven is lined with carnage.

They aren’t trying to be racists or misogynists or fascists. They just want you to get saved. They want America to be saved.

Like Ted.

And so, we’re all being thrust into their revival tent, pushed down their sawdust trail. Sit down. There. On the mourners’ bench — while the choir sings “Just As I Am.” The buses will wait.

“Our system needs to be broken, and he is the man to do it.”

Jesus? Or Donald Trump?

Sadly, I think I understand.

INSPIRATION

THE FUNDAMENTALISTS IN HEAVEN

discover they’re correct:

the mullahs, rabbis and the preachers,

the televangelists

complete with sundry

flocks and herds — the metaphors

have slipped through with them.

They’re wearing robes like Bedouins

from Bible illustrations.

The decor’s indistinct but still

a kind of middle eastern —

palm trees, minarets and fountains,

a Cecil B. de Mille affair. . . .

The end of all their expectation

is literal in evening light

where they must dwell at least forever

elbowing the saved.

— Geoff Page, read the entire poem HERE

Conventional wisdom, at least in white Christian circles, has assumed that upstanding white churches safeguard democracy. But today, studies that trace anti-democratic sentiment to its source indicate that these threats may be coming from inside these houses of worship.

— Robert P. Jones, President of Public Religion Research

and author of the newsletter, White Too Long

Dear Diana,

Pretty damn depressing. Thanks. Well you know, thanks for nothing or maybe thanks for everything. I hope you are wrong and I expect you are right. I can still here the voices of the altar calls at a Jack Wertsen rally. I was 16. Never raised my hand but never got the voice out of my head....well that is not right. That voice just annoys me now. It has not power. The struggle now is somehow to not let the heart hate those who deliver you are no good message. The struggle is to love the ones who I do not agree with or hang a 4' by 8' Trump Forever Sign across the street from my house or hand a "Fuck Biden" sign next to their Christmas manger scene. I have a silent prayer that asks the creator for help loving my way out of my anger. I invite my neighbor to have his children sleigh ride on the hill on my property. We are civil to each other but we do not communicate. Sorry about the rant. Love to read your stuff. Thanks for ruining Thursday. I am a Lutheran pastor getting ready to bury a 16 year old great kid who jumped in front of a train on Monday. I heard 30 scolds of Trumps victory talk on Tuesday and got nauseated. An hour ago I was hugging a women in tears whose daughter had said no to dating the 16 year old boy who jumped in front of the train. People are dropping off gift cards and food and cards and tears because some one they know is suffering. Life is complicated. Politicians are out of touch. Jesus would not recognize some people who call themselves Christians. Jesus was the first to cry when the train hit Riley. How do we stop feeling powerless? How do we use love to make the world safer for everyone? Once again sorry about the rant. I do not expect anyone to read this anyway but it has helped me. Blessings to you and the truth of your voice. Niels Nielsen

Thank you and Amen!

I grew up in one of those evangelical families. I have family members still trapped in that kind of cult church. My. uncle was a very hard shell Baptist preacher. As a small child I used to wake up with nightmares of burning in Hell. My grandmother took me with her on cold calls to “save” people. I was finally not allowed to attend services in the Baptist church. I am happily an ELCA Lutheran, where we believe all are welcome.

It seems to me these Evangelicals think they know the mind of God. I think that makes God rather small.

I am happy you mentioned Heather Cox Richardson. Like you, she keeps me sane, and informed.