Fall is upon us! The Cottage is celebrating turning leaves and sweater weather with an autumn equinox surprise subscription offer: THE PUMPKIN SPICE SPECIAL!

New subscribers (and those upgrading from free to paid) receive an extra 10% off a regular yearly subscription (which is already a really good deal). You can use the extra cash to put toward a Pumpkin Spice Latte (everybody’s favorite drink to hate). This offer is good ONLY until OCTOBER 4 (St. Francis Day).

I live in Alexandria, Virginia, a small city rich with memory. Its two most famous residents were George Washington and Robert E. Lee, more controversial figures now than in the past, but they hardly hog the local historical stage. One can’t walk a block without some plaque commemorating another famous American, a significant building, or a past event of note.

For those fascinated by history — like me — Alexandria is like living in a museum. Or, perhaps, an archeological tel. There’s always some new discovery of what is old. Digging up the past is a daily occurrence.

When it comes to historical sites, I’ve always found graveyards compelling. Not in some goth or death-obsessed way, but because tombstones tell stories of people long gone, with their names and dates, favored Bible verses and poetry quotes, hopes and heartbreaks inscribed in stone. As I walk around and read the sketchy, carved details, I wonder: How did that family survive mother and infant dying on the same day? Was that young man killed in the war? What was it like to live to be 80 at a time when most people died before 60? Cemeteries and columbaria are built landscapes of memory and imagination.*

Unsurprisingly, Alexandria is full of graveyards. During my first few years here, I worked at Virginia Theological Seminary, where a small graveyard holds the bodies and bones of long-gone professors and priests. At the same time, I also worked at the first church in town, whose yard is the final resting place for parishioners who died before the Revolutionary War. Historical rumor has it that the second church was founded because of a conflict over that graveyard. When one early rector of the church buried his mistress — a notorious actress — in this sacred ground, his more pious congregants, shocked by the “desecration,” broke away and started a rival church down the street.

But no conflict over Alexandria graveyards exceeds that of the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetary, a burying place at the southern edge of town.

If one drives south out of Alexandria toward Mount Vernon, you can’t miss an old, large cemetery — St. Mary’s. Its entrance marked by old gates and a brooding Victorian angel. Now, it borders the DC Beltway. In 1795, however, the year St. Mary’s was founded, the land was just outside the city, just above a swampy marsh on the Potomac.

There’s a reason for its location, distant and isolated as it was from the center of the busy port. St. Mary’s was for Catholics. Indeed, it is the oldest Catholic cemetery in Virginia, where Catholicism was prohibited by law until 1786. Even after the ban was rescinded, Catholics faced discrimination. The Protestant majority suspected Catholics being traitors and “foreign.” Their church, begrudgingly permitted, was relegated to the edge of town, as was their cemetery. The burial place for the Catholic dead was considered unAmerican, unChristian, and vaguely unclean — it needed to be far away from “decent” people.

The Catholic cemetery is an obvious landmark, but there’s another graveyard across the main road that has been far less so. When I first moved to Alexandria in 2000, someone mentioned that there was a Black cemetery nearby.

But I couldn’t find it. There was no cemetery across from St. Mary’s.

There was, however, a sign — a state historical marker erected in 2000, the same year I first lived here:

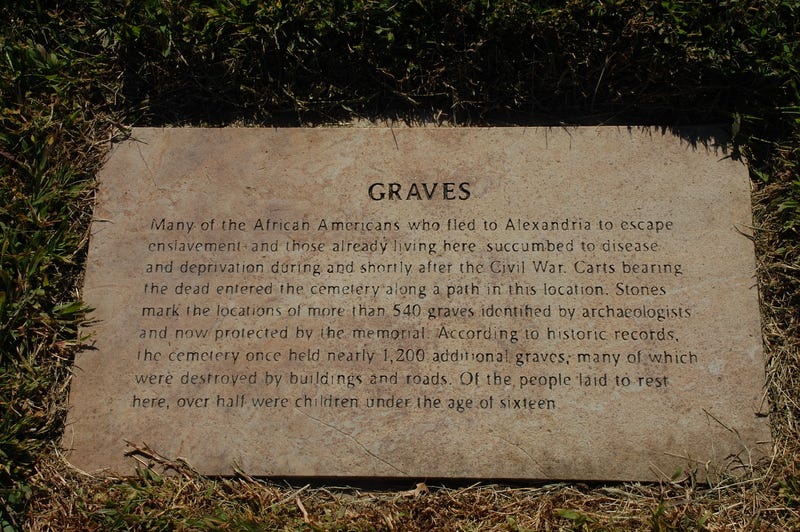

Federal authorities established a cemetery here for newly freed African Americans during the Civil War. In January 1864, the military governor of Alexandria confiscated for use as a burying ground an abandoned pasture from a family with Confederate sympathies. About 1,700 freed people, including infants and black Union soldiers, were interred here before the last recorded burial in January 1869. Most of the deceased had resided in what was known as Old Town and in nearby rural settlements. Despite mid-twentieth-century construction projects, many burial sites remain undisturbed. A list of those interred here has also survived.

The Union army occupied Alexandria at the beginning of the Civil War, and it became a refugee city for those fleeing enslavement from across Virginia and the upper South. The black population swelled, and the immigrants, who arrived desperate straits, faced crowded and unsanitary conditions that led to outbreaks of typhus and smallpox and the death of scores of the formerly enslaved.

The authorities seized land near the undesirable Catholic cemetery and turned it into a graveyard for African-Americans — the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery — and the southern end of Alexandria became a vast burial ground for those not entirely welcomed by society. In just five years, spanning the end of the war and early Reconstruction, almost 1,800 Black people were interred there, in a burial place paid for and maintained by the federal government.

When Northern military rule ended in 1869, Alexandrians moved to undo whatever the Yankee occupiers had done for benefit of the African Americans. Reasserting white supremacy, city leaders abandoned the cemetery. Survivors of Black soldiers buried with the “contrabands” had their loved ones’ remains transferred to a new national military cemetery and a more dignified resting place. The graveyard succumbed to terrible neglect and desecration. In 1892, the Washington Post reported that only a single tombstone remained standing at the old burial ground. Within a few years, the cemetery disappeared from both local maps and civic memory.

During the 1950s building boom, several uses were suggested for the largely deserted land including putting a new luxury motel. Eventually, however, a gas station and an office building were constructed on the site in 1955. Both were still in business at the turn of the millennium, with their foundations dug right into the graves of the dead.

I dreaded driving past the place — something I did everyday for several years. It was appalling. I couldn’t understand how a gas station stood atop an historical graveyard. The way we treat the dead often reveals how we treated people in life. The casual disregard, the purposeful desecration, and commercial destruction of human remains proves what African Americans have long insisted — Black bodies don’t matter. Not at birth, not in childhood, not at work, not in full citizenship, and not at death. And certainly not in history.

Graveyards are not only reminders of our end and questions of eternal life; they mirror the actions of this mortal life. If you dispose a body like trash in death, it is a pretty good chance you treated that person the same way when they lived. Care for the dead is the ultimate test of the Golden Rule: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Sadly, erasure of the dead is a common story across the United States. Old cemeteries are often at risk — of disrepair, development, and demolition — no matter the race or class those interred. There is, of course, no way of knowing how many graveyards have been forever lost. But the graves those marginalized in society, especially American Americans and Indigenous people, have been most callously disregarded and destroyed. Those burial places hold not only forgotten bodies, but forgotten stories. And some people were fine with disposing of both.

We walk on this history all the time, tripping over the past and its injustices, unaware of what lies underfoot.

There is, however, a reckoning unfolding in our days. Recently, I shared the story of the Alexandria cemetery at a church in Clearwater, Florida. The audience reaction surprised me — their city (and the larger region around Tampa Bay) is coming to terms with Black cemeteries, hidden for decades under commercial and civic buildings. In a state now riven with conflict over teaching American history, the work to restore and learn from these sites is expanding and even serves as a national model for their recovery. There are similar movements in other states and on a federal level, as well. And it isn’t just the United States. Canada is coming to terms with its graveyard history, as the painful story of their First Nations people now reveals.

During my daily commute, I was unaware that, in 1987, an Alexandria city historian had rediscovered the forgotten story of the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery. Even as I drove by in dismay, a process of righting the wrongs of the past was well underway. It took more than twenty years to identify the site, reacquire the land, conduct library and archeological work, take down the buildings, trace burials and descendants of the dead, and design, fund, and erect an appropriate memorial. Good history is part detective work, part excavation, part civic therapy, part imagination. Finally, in 2014, the city dedicated a memorial park at the cemetery, now recognized as part of the National Underground Railroad Network and the African American Civil Rights trail.

The new park is moving tribute to the human spirit. The gas station has been replaced with a soaring monument — Mario Chiodo's sculpture, “The Path of Thorns and Roses” — to freedom and the struggle to attain it.

In an age when so many white Americans are anxious and fearful about statues coming down, it is worth paying attention to statues that are going up. I’ve heard people bemoan that history is being “taken away” and memories of the past “buried.” They ask why, resorting to the comforts of a romanticized past, and put trust in politics promising a return to familiar histories. Nationalist parties are fueled by slogans of the historical privilege: Don’t take away our history.

Movements of malignant nostalgia ignore the more important questions: What has already been buried and forgotten? Whose history has been paved over by the powerful? What lies underfoot? Are there memories we must excavate to be know the truth and be set free?

Answering these questions is the work of history — researchers, archeologists, and storytellers. It is the work of civic groups and political leaders. All of us, really. Because this is deeply spiritual quest to honor bodies, respect human dignity, and resurrect stories our ancestors buried. It is about living with deep honesty instead of delusion.

Jesus famously said, “Let the dead bury their dead. You go and proclaim the kingdom.” While I get his exaggerated point, we must recognize that how we treat the dead witnesses to our fidelity — or failure — to practice the very kingdom we preach.

*There’s a contemporary discussion that we humans have used too much land on the construction of these spaces. It is a worthy and important conversation related to environmentalism, economic justice, and climate change. Moving toward more sustainable ways of honoring the dead is needed, and those concerns do not mitigate the historical and theological concerns raised in this piece. Indeed, they are related and deserve careful consideration.

INSPIRATION

When we bury the old, we bury the known past, the past we imagine sometimes better than it was, but the past all the same, a portion of which is inhabited. Memory is the overwhelming theme, the eventual comfort.

― Thomas Lynch

They came as Congo, Guinea, & Angola,

feet tuned to rhythms of a thumb piano.

They came to work fields of barley & flax,

livestock, stone & slab, brick & mortar,

to make wooden barrels, some going

from slave to servant & half-freeman.

They built tongue & groove — wedged

into their place in New Amsterdam.

Decades of seasons changed the city

from Dutch to York, & dream-footed

hard work rattled their bones.

They danced Ashanti. They lived

& died. Shrouded in cloth, in cedar

& pine coffins, Trinity Church

owned them. . .

— Yusef Komunyakaa, from “The African Burial Ground,” please read the entire poem HERE

The cold storms of winter shall chill him no more,

His woes and his sorrows, his pains are all o’er,―

The sod of the valley now covers his form,

He is safe in his last home, and fears not the storm.

The poor slave is laid all unheeded and lone,

Where the rich and the poor find a permanent home;

No master can raise him, with voice of command,

He knows not, he hears not, his cruel demand.

Not a tear, not a sigh, to embalm his cold tomb,

No friend to lament him, no child to bemoan;

Not a stone marks the place, where he peacefully lies,

The earth for his pillow, his curtain the skies.

Poor slave! shall we sorrow that death was thy friend?

The last, and the kindest, that Heaven could send:―

The grave to the weary is welcomed and blest;

And death, to the captive, is freedom and rest.

— Sarah Louisa Forten, “The Grave of a Slave” (1831)

Every life holds an epic tale, even if no one alive remembers it.

― Greg Melville

SOUTHERN LIGHTS IS NEAR!

January 12 -14, 2024

And our theme is Reimagining Faith Beyond Patriarchy and Hierarchy

Last January, almost 700 people gathered at St. Simon’s Island in Georgia for a packed weekend of poetry, theology, and music.

WE’RE GATHERING AGAIN!

YOU ARE INVITED to join me and Brian McLaren as we reimagine our faith beyond patriarchy and hierarchy in our interior lives, in our communities of faith, and in the Scriptures. We’ve asked three remarkable speakers to take us through this journey: Cole Arthur Riley, Simran Jeet Singh, and Elizabeth “Libbie” Schrader Polczer.

Please come and be with us in Georgia. SEATS ARE LIMITED! Or, if you’d rather be with us online, you can choose that option as well.

MORE INFORMATION AND REGISTRATION CAN BE FOUND HERE.

I’ll be at Plymouth UCC in Fort Collins to preach on Sunday morning, October 1 and lead an evening conversation/workshop on gratitude that same day.

Information can be found HERE.

Sometimes I stand among the stones and wonder. Sometimes I laugh, sometimes I weep. Sometimes nothing at all much happens. Life goes on. The dead are everywhere.

― Thomas Lynch

Not sure anyone will actually read this...posted so late as it is. BUT but I've always wondered -- aside from the very fleeting acknowledgement of wrong doing by the mostly-still-clueless-of-what-was-done descendants of the "doers" who can do little or nothing to rectify a decades/centuries old wrong -- what real/actual "good" is done by digging up the past and waving it under the noses of those who were NOT responsible for the wrong that was done. And I've also wondered why no one in Germany and the world saw/anticipated that the final outcome (the one we are living in now) of the long, loud and very public chastisement of GERMANS (the guilt tripping) , most of whom were powerless to do anything to rein in the Third Reich's evils, would lead to. I'm not talking just about the backlash from the guilt-tripping/blame that resulted in the NeoNazism in Germany that spread outward from there. I'm talking about punishing people for something they could not do anything about (without also endangering themselves, their families, their friends....everyone they knew). That kind of "justice" (and the arbitrary creating of several nation states) helped set the world stage for where we are now.

Such an important writing! I will share this. It is such a comfort to know that we are beginning to recover and tell the truth in this country. I am late in reading this post. It makes me wonder what will happen to the people taken hostage, murdered, and killed this week in Israel and The Gaza strip. What happens to the bodies of all nations buried under rubble from missile strikes? What about the unidentified ones?