Discover more from The Cottage

Over the last few days, I spent seven hours watching the remarkable new Netflix series, Midnight Mass. Done in the genre of horror (which I generally eschew), Midnight Mass follows a group of (mostly) church people whose world is collapsing - and the choices they make when facing the last things. At its heart are questions: Is Christianity about a sacrifice for the life of the world or a sacrifice for personal salvation? Is it about the power of wisdom or the power of eternal life? And how do faithful people choose the right way when facing apocalypse?

The series is so theologically rich - and disturbing - that I texted my friend David Dark (please check out his “Dark Matter” newsletter) and asked him what he thought. He said that Midnight Mass reminded him of the Decalogue. David’s remark called to mind Moses’ instruction to Israel who, at the end of their wanderings and as they contemplated what their new world might hold, had to choose what kind of people they would be: “See, I have set before you today life and prosperity, death and adversity.” That way or this. Endings and beginnings aren’t easy. They don’t just happen. There are choices to be made.

Everywhere we turn our lives seem threatened by apocalypse: climate, economics, politics. I’ve even written a book with the subtitle, The End of Church! How do we live at the end of the world? We have choices to make.

Some Christians argue there is no choice. That our only choice is to turn our backs on a fraying, fractured, evil world and form an exclusive community of true believers - who can, when called upon, destroy the wicked and restore godly society. That’s the vision laid out by Rod Dreher in a book originally published in 2017, The Benedict Option, where he urges Christians to reimpose “Christian belief and Christian culture” to save the west.

That’s the major temptation in Midnight Mass, too.

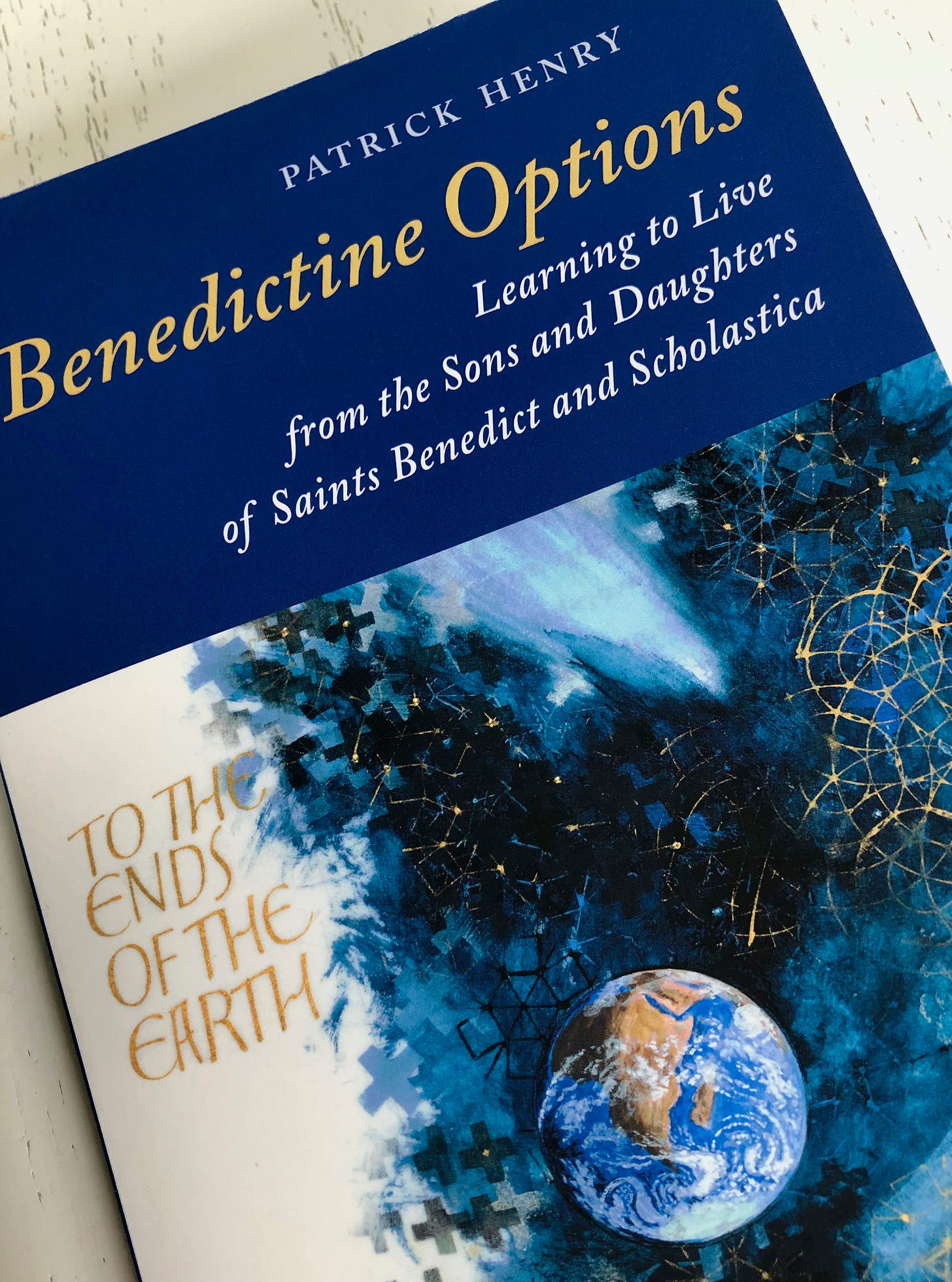

But there’s a different way. Some of the characters in Midnight Mass figure that out. Oddly enough, as I was watching the Netflix series, I was also reading my friend Patrick Henry’s wise book, Benedictine Options, which criticizes Rod Dreher’s view of things. Patrick argues that St. Benedict didn’t turn away from the world but learned to see the world more deeply - and “his spirit was enlarged.”

I won’t tell you what happens in Midnight Mass. But Patrick Henry reiterates the call to love and live here and now in a fully human way, “a world-embracing monastic spirit” of faith that is “experimental, rhythmical, communal, ecumenical, and ‘narrational.’” While Dreher sees ours as “a world growing cold, dead, and dark,” Patrick insists that “Benedictine options are for a world of many colors” - aglow with laughter and lightness and love.

“What, finally, is the consequence of implementing Benedictine options? It’s the opposite of The Benedict Option’s withdrawal. . . It’s being alert to what God says in Isaiah (43:19): ‘I am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?’ The ‘new thing’ appears in the world - the whole world - that Benedict saw in his vision. Benedictines are connoisseurs of surprise.”

We can choose to turn away from the end of the world, in the process, turn ourselves into monsters - or turn toward it and see a loving, healing, forgiving, and hospitable God even there. When we fear we’ve reached the end. We have choices. Surprises await.

Choose well.

GUEST ESSAY

BENEDICTINE OPTIONS: EMBRACE, NOT ESCAPE

Today’s guest at The Cottage is Patrick Henry who lives in Waite Park, MN, and was professor of religion at Swarthmore College and served as the executive director of the Collegeville Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Research. Now retired, he is a monthly columnist for the St. Cloud Times and is author of Benedictine Options: Learning to Live from the Sons and Daughters of Saints Benedict and Scholastica.

* * * * *

POLITICAL AND RELIGIOUS conservative pundit Rod Dreher spent four months earlier this year at the Budapest Institute, which is closely aligned and allied with Hungary’s authoritarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán, whom Donald Trump effusively praised at the White House in May 2019. According to a story in the Sept. 13 New Yorker, Dreher says Orbán believes “there’s no way Europe is going to survive long term unless it rediscovers its religion.” Dreher thinks America faces a similar threat.

Dreher prescribed this “rediscovery” in his 2017 bestseller, The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation. Dreher sees a world growing “cold, dead, and dark,” and says that people need to imitate monks who secede from mainstream culture. He celebrates what he calls “today’s Benedicts,” sailing in “arks capable of carrying them and the living faith across the sea of crisis—a Dark Age that could last centuries.”

The Benedict Option, called by David Brooks “the most discussed and most important religious book of the decade,” is a wrongheaded book in any decade, with serious political and social consequences. Dreher’s caricature of monasticism, spread widely by the more than 70,000 copies sold in the US and translation into a dozen languages, is a distorted “rediscovery of religion” that can easily be lassoed by just about any authoritarian.

Here’s what Dreher “learns” from Benedict: withdraw from the world; form separate communities where your children will play only with others whose values are the same as yours; pull your kids out of public school and teach them the tradition of the Christian West (Dreher loves the definite article “the”); and classify endorsement of gay marriage and transgender rights as “modern repaganization.”

What follows from this is Dreher’s amplification of our current social and political acrimony: “there is no middle ground”—a phrase that fits neatly in an authoritarian creed.

But from the beginning, Benedictines have occupied middle ground.

Monastic women and men, witnessing the rise and fall of “modern world” after “modern world,” have maintained skepticism of both Dr. Pangloss’s contention that this is the best of all possible worlds and Chicken Little’s warning that the sky is falling.

The 6th-century Rule that shapes their life has survived for a millennium and a half not because it has shielded them from “the world,” but because it is flexible—for example, it claims to be only for beginners; the superior is to take every monk’s idiosyncrasies into account; the community should pay special attention to the ideas of the youngest; and, Benedict says, if you can think of a better way to do something, do it.

There is no more compelling or engaging a depiction of this than Ellis Peters’s twenty mystery novels, Chronicles of Brother Cadfael, a 12th-century herbalist who enters the monastery relatively late in life after some swashbuckling adventures in the Crusades. Cadfael and his confreres are so intricately linked to the life of the surrounding community that you realize the monastery wall, far from being an impenetrable barrier, is a thoroughly permeable membrane. True in the 12th century—and in the 21st, as I have seen it up close for nearly half a century of living near and working with Benedictines.

What have monastic people been practicing for sixty generations? Not a sequestering in the company of the like-minded. Not a kind of ideological redlining. Not a sort of gated community. And certainly not huddling in an ark sailing across a sea of crisis. Rather, the most prominent Benedictine in the US, Sister Joan Chittister—as averse to withdrawal from the world as anyone alive—has said of Benedictinism that it serves “as a mirror to the world around it as it defines and redefines itself from age to age.”

At this particular time, when tribalisms that are fodder for authoritarians are in the ascendent, Benedictine curiosity about and openness to others goes way beyond Dreher’s focus on Christians. Benedictines are in the forefront of interreligious dialogue, especially with Buddhists and Jews and Muslims.

Benedictine options (note the plural) are an antidote—far more thoroughly time-tested than any of the other available prescriptions—not only to culture wars and authoritarian threats, but also to the monochromatic and pinched Benedict option put forth by Dreher.

If authoritarians—whether Orbán or Trump and his GOP enablers or others—were to look at monasticism as Benedictine women and men actually live it, instead of through Dreher’s disfiguring lens, they would not like what they see.

PATRICK HENRY WILL BE MY GUEST on the Cottage’s private podcast, The Secret Garden. UPGRADE to be a supporting subscriber in order to receive The Secret Garden with him on Tuesday, October 5.

Also, the supporting subscribers are all invited to a LIVE ZOOM to the The Cottage on October 7 at 7PM eastern with Libbie Schrader sharing her work on Mary Magdalene!

To upgrade, click on the “subscribe now” button below:

If you have a question for Patrick leave it in the comment section - I’ll try to ask it when we record the podcast!

INSPIRATION

Listen and attend with the ear of your heart.

― St. Benedict of Nursia

Authenticity is a collection of choices that we have to make every day. It’s about the choice to show up and be real…to let our true selves be seen.

— Brené Brown

Early February evening.

Benedict and his twin sister Scholastica,

talk for hours about dealing with wayward

monks, childhood memories, regrets, and how they

sometimes steal away to the forest to dance.

The beeswax candle extinguished, she

went to fetch another, dinner plates

pushed aside with drips of grease left from

roast chicken, celebrating this yearly

time together, the extra jug of wine nearly emptied.

He gets up to leave but she protests.

Benedict’s own Rule, requires him

to be back at his monastery overnight.

Perhaps she knew she would die only three days later.

Or maybe the rose-hued glimmer of evening astonished her.

Or this was one of those moments she just wished

would linger on, her brother’s beard shining

silver in the growing moonlight, wanting to

remember the great brown kindness of his eyes,

feeling the rough warmth of his hands in hers.

Her tears rise up, falling in great splashes,

her weeping calls forth a fierce rainstorm.

Cosmic forces come down on the side of love,

demanding that self-set rules be broken.

I imagine the two of them listening to

the relentless rain beating down around them,

Benedict yielding to the moment, suddenly

seeing the necessity of riverbanks, but also the

widening expanse into the sea.

Perhaps that night they each dreamt that the river

swelled so high it lifted them to the blue bowl of sky,

until the horizon hallowed them.

Until he could see far beyond the stone walls

he had so carefully built.

— Christine Valters Paintner

I clearly recall the outstanding New Testament class I took with Patrick Henry at Swarthmore about 1969. It helped me on a path as a seeker, which has greatly expanded its vision as I grow older. I wish him the best.

Hi Diana,

First thank you for pointing out these books and most importantly the themes in them, and how one of the books in particular-misses the point of St Benedict’s approach. I would say further that he misses the import of the eschatological portions in the gospels, which are rich in their ethical and moral aspects-and treating the least of these and how we treat them, is how we treat-when I was in prison, you visited me, when I was hungry-you fed me. This is not a retreat from the world-it is engaging it’s injustice with love and justice-not even to, but especially to, the least of these.

Again thank you for pointing out the need to engage Vice retreat from the world.

For the heart of the Christian faith is God so loved the World-love is nothing if it’s not engagement.

We are called to engage-St Benedict, St Francis, the Early Church-engaged. Jesus-engaged-God..engages-while we were yet sinners as the Pauline writings would say in concert with the gospels-while we were at our furthest in alienation (sin) -Christ loved us to the point of death-even that on a cross.

No, he’s mistaken Benedict, Francis, the Early Church, and the gospels.

Thank you also for the reference to the Netflix series. I will certainly watch it. Much respect.