Do Nations Have Souls?

We take might take the answer for granted, but we need a new vision of the question.

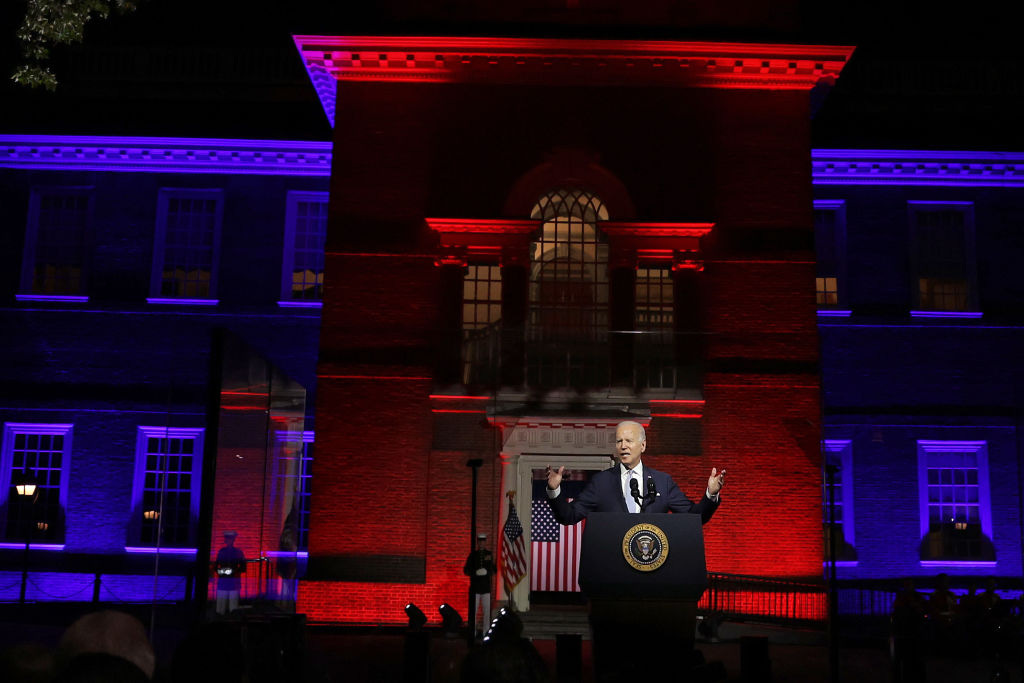

If you haven’t read or listened to President Biden’s speech last night (September 1) about the “battle” for the nation’s soul, I strongly encourage you to do so. Biden is not and never has been an orator, but he’s a man who speaks from his heart. You could hear how much these twenty-four minutes of reflecting on the current state of American society and politics meant to him. It was, in some ways, an old-fashioned sort of civil religion address. He appealed to enduring American ideals including equality, liberty, and the image of the nation being “a city set upon a hill.”

But the context was stark — and quite unlike presidential remarks I’ve ever studied or heard — that we are under a grave threat of domestic violence, and are roiled by division that could literally destroy American democracy. Thus, the speech is a moving admixture of unnerving worry and oddly optimistic hope for a better future.

The remarks were titled, “The Continued Battle for the Soul of the Nation.” While some — especially the Republican critics on FOX news — may hone in on the word “battle” as being divisive, the word “soul” draws my attention. Soul is a distinctly philosophical and religious term, the notion that some part of us is spiritual and immaterial, something that includes our hearts and character, that is both deep within us but lasts beyond us.

Most (but not all) people accept the idea that human beings — as individuals — have a soul. But do nations have souls?

When we hear the word “soul,” we typically think of individuals having a soul — as a kind of quality implanted in us even before birth, generally understood as a connection with God, the divine, or the spirit as having existence beyond bodily life. Because of this, some souls were special or set apart, “chosen” for particular roles or work, gifted by the gods for an eternal purpose, one that is, in effect, “immortal.” When we’re born, our bodies house the soul. Death separates body from soul, and notions of life after death often include some hope of reunification or resurrection where the two will be united again. These ideas developed in the ancient world, especially influenced by religious conceptions in Egypt, Greece, and Rome — and continue on to today, carried into the modern world by Jewish, Christian, and Islamic modifications of them.

Other ancients saw things differently. Everything — people, animals, plants, non-biological entities, places — had animating spirits, a kind of power that can be accessed and manifested by individuals, in tribes, and through rituals. In effect, soulfulness — the spiritual power of life, for good or evil — was everywhere in all things, traces of the gods and their gifts for a people who inhabited a particular land. It wasn’t an individual quality, it was simply part of the way things were. In this view, body and soul couldn’t really be separated. Your body was born into an ensouled world. In that context, people learned to read the land, discern the signifiers of spirit within and without, and flourished insofar as these spirits were in harmony.

What does “soul” mean in American history?

* * * * *

When American presidents speak of the “soul of a nation,” they are typically appealing to the idea of soul from the classical world passed down to us through Christianity. American rhetoric is filled with the notion that this political entity has a soul — of being a chosen nation, a New Israel, and a “city set upon a hill.” All of these images of soul imply that somehow, before the United States was a political identity, America was conceived by God, knit in the womb of divine providence, born in the fullness of time. Not just individual Americans, but the nation itself was implanted with a soul — a sacred mission and a spiritual role to play in the world’s destiny.

If you understand American soulfulness in the classical-Christian way, it is easy to get into trouble. A divinely-sanctioned America becomes, as G.K. Chesterton once averred, “a nation with the soul of a church.” That is dangerous because churches often have a very difficult time discerning God’s purposes from human ones. To believe a political community is also a religious body is one of the most egregious mistakes of western history — to claim whatever the nation does is God’s will and that God’s will is whatever a nation does. It can be difficult for a political body to admit that it has failed at its divine purpose, having failed God. And yet, since its beginning, the language of “American soul” has somehow been with us.

The classical-Christian notion of a national soul has two major forms in the United States. The first is that America is a Christian nation (or, in a more recent iteration, a “Judeo-Christian” one). America’s soul is a specifically, purposely, and divinely designed Christian one, based in the teachings of scripture and fidelity to Jesus. To depart from this is to anger God, and the nation must continually return to its singular identity as Christian to fulfill its destiny.

The second form of American soul also involved notions of being specially formed and called. But that formation and calling came not through biblical scripture but by a “sacred” constitution of political documents written by a generation of “inspired” founders. A vaguely divine presence was somehow at work in this, and the Bible served as a kind of assumed moral text, but soulfulness was primarily articulated in an Enlightenment creed of equality, liberty, freedom, and justice — and crafted by human hands. When America fails to live up to this, the nation doesn’t incur God’s wrath. Rather, America can fail faithful generations past — and the possibility of such failure — shame, really — can rouse those in the present to defend the nation’s sacred ideals.

Thus, the American “soul” is shaped by both classical and Christian ideas, creating a kind of mutually-informed understanding of American identity. Although one definition leaned more specifically into the Christian conception of soul, and the other more toward its classical influences, the tensions between the two only occasionally resulted in rhetorical or political conflict. Many Americans found meaning in this blended civil expression of national soulfulness. Even those who were excluded by race and gender appealed to the ideal of the national soul — usually to point out that America had betrayed both its Christian and secular creeds.

But the classical-Christian soul narrative didn’t hold. And that’s a big part of the problem right now. In the late twentieth-century, white evangelical Christians were unhappy with the classical parts of this synthesis and rejected it. They launched a project to rewrite American history claiming that the founders were orthodox Christians and that the nation was specifically chosen by God for a divine mission to the ends of the earth.

At the same time, the United States was becoming more religiously diverse — and contemporary philosophers less enamored of the Enlightenment. Thus, the Christian notions of American soulfulness seemed too exclusive for a pluralistic democracy. The very idea of a “civil religion” came increasingly under fire, and that cynicism combined with an academic project to deconstruct concepts like equality, liberty, and justice. By the early twenty-first century, the classical part of the American “soul” was nearly undone. The tradition was revived by President Obama in a spiritually and racially inclusive way that included recognition of national failures — but its complexities and nuance were too hard for some Americans to hear.

All of this left the notion of an American soul in rhetorical shreds. One half of the old synthesis mutated into a full-on white Christian nationalism; the other part has transformed into a more pluralistic and self-reflective notion of national identity that is currently under fire as “socialist.”

The American soul might not be at war. But it certainly is divided. And that’s the some of what is behind Biden’s call to battle.

* * * * *

All of this takes me back to that alternative conception of the soul. Perhaps the classically informed Christian “soul” was always the wrong way to approach the question of whether nations have souls. It seems that the other vision is more on target:

Soulfulness — the spiritual power of life, for good or evil — was everywhere in all things, traces of the gods and their gifts for a people who inhabited a particular land. It wasn’t an individual quality, it was simply part of the way things were. In this view, body and soul couldn’t really be separated. Your body was born into an ensouled world. In that context, people learned to read the land, discern the signifiers of spirit within and without, and flourished insofar as these spirits were in harmony.

I recently spent two weeks at Ring Lake Ranch, a retreat in a valley in the Wind River Mountains, outside of the small town of Dubois, Wyoming. One day, while I was in town, a store owner said to me, “Oh! Ring Lake Ranch! That place has such an amazing spirit. You can feel it.”

Yes, it does. And yes, you can. Ring Lake has a soul. It has for a very long time. Thousands of years ago, indigenous men from the tribe known as the Sheep Eaters came to the shores of the lake on vision quests and recorded their spiritual journeys in petroglyphs they carved on the rocks.

As you hike around the ranch and its surroundings, you can feel that something calls, it hangs in the thin, clear air, and the the rocks themselves seem to cry out. It is a world inhabited by meaning, where everything speaks. The main job of the visitor is to enter the landscape and listen.

What if the American soul isn’t something we defend or battle?

What if soul isn’t something that we possess but something that possesses us?

Maybe souls don’t dwell in bodies but bodies dwell in an environment of soul.

Could it be that American soul is in the rocks, carried by winds, rivers, and streams, scattered across the sky in the stars? Our spirit is in the laughter of children and the questions of searching adults? America’s soul is a landscape of geography and history, of how good and bad choices mysteriously shape us, of connections through time that we rarely acknowledge. Perhaps soul is just here, it always has been. Everywhere. Before us, after us. Waiting for us to hear and see it, to understand the sacred all around — to envision how we should live, gather, steward, and care in relation to the soulful universe in which we dwell.

The Bible does have stories of being chosen — of individual souls and the souls of nations. But it also tells this other story as well — that God creates all, dwells in and with all, and everything dwells in God. In effect, everything is chosen, everything is soulful, everything bears the imprint of the divine, and the holiness of spirit gives life to all.

Perhaps it is time to end — not continue — the battle for the American soul. Instead, it is time to envision the shared soulfulness we inhabit. Maybe we’ve been warring with the alternative possibility — misunderstanding soul as somehow special for only certain people and nations — and that battle is the source of our deepest sadness and most profound divisions.

Instead of continuing the battle for the nation’s soul, let’s embark on a new vision quest. Together.

The Cottage is a place of reflection and conversation on faith offering perspectives often overlooked in public discussions of religion. We’re exploring the role of religion and spirituality in culture and politics in ways you’ll never hear in the media — with ideas that matter. We’re cultivating a different kind of garden with plots of goodness, compassion, and understanding.

Join us. Everyone is welcome.

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support this work financially.

INSPIRATION

In our finest hours...the soul of the country manifests itself in an inclination to open our arms rather than to clench our fists; to look out rather than to turn inward; to accept rather than to reject. In so doing, America has grown ever stronger, confident that the choice of light over dark is the means by which we pursue progress.

― Jon Meacham

One ever feels his twoness — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

― W.E.B. DuBois

AmeRícan, defining the new america, humane america,

admired america, loved america, harmonious

america, the world in peace, our energies

collectively invested to find other civili-

zations, to touch God, further and further,

to dwell in the spirit of divinity!

— Tato Laviera, from “AmeRícan,” read the entire poem HERE

Recognize whose lands these are on which we stand.

Ask the deer, turtle, and the crane.

Make sure the spirits of these lands are respected and treated with goodwill.

The land is a being who remembers everything.

You will have to answer to your children, and their children, and theirs—

The red shimmer of remembering will compel you up the night to walk the perimeter of truth for understanding. . .

— Joy Harjo, from “Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings,” read the entire poem HERE

FALL EVENTS

Please check out my Fall events calendar. Hope to see you at one of these virtual or in-person gatherings! Check back for updates!

BOOKING FOR SPRING 2023 and BEYOND

Church planners: Lent is coming! (At least Lent planning is at hand!) I’ll be talking about Freeing Jesus and the spiritual practice of memoir this spring on the road.

You can book me for your college, book group, conference, or church weekend by contacting JIM CHAFFEE of Chaffee Management. Spring dates are filling up fast — so reach out soon.

Hey, and I am sorry but I am gonna run way off from the meat of your good post's point, but,, I tell you what, I don't know about the soul of a nation but I rejoice in somebody finally punching maga right square in the nose. My opinion,, but, I think this is how you need to fight a bully and is long long long long overdue, and I do hope this is the beginning of the end for this clan of crazies.

Sorry to rant.

Thanks for room to post.

Richard Rohr (and perhaps others, too) has referred to creation as the first incarnation. There is a pre-existent Presence that permeates all, but most of humankind is permeated by perceived “matters of consequence” (see Antoine de Saint-Exupery in The Little Prince) and live obliviously to the Presence, wherein each and all of us will find our ground of being—our Story and stories—if we but still ourselves and wonder. The ancient cultures are our best chance for renewed revelation to this fully accessible Truth. May we be open to Wisdom as she persists. Thank you, Diana, for this marvelously full and soulful offering. Peace…