There was a spam problem earlier today at Substack. Some of you may have received a reply to a comment from someone pretending to be me, asking you to text me at a certain number. This mostly happened around 7:30 eastern time.

IT WAS NOT ME. I would never send such a spammy-looking comment or solicit your information or phone number in any way. Please DO NOT reply to a text like that. I have blocked the imposter and deleted all the fake replies. But you may still have a reply notification in your email that is visible only to you. DO NOT REPLY TO IT.

I’m deeply sorry for the nuisance. This has happened to a number of Substack writers today. I’ve alerted Substack that The Cottage was spammed. If there is any follow-up from them, I will let you know.

As always, thank you for being part of The Cottage. In our online age, there are always bad actors. Please know that this wasn’t a hack. It was spam — more of a bother than anything harmful. I’m confident that Substack will work to make sure this doesn’t happen again.

During Epiphany, we’ve been exploring themes of light. In this post, you’ll find a reflection on my recent visit to the powerful memorial dedicated to victims of lynching — and how it shines a light on America’s history of racial brutality. There’s a moving poem by Elizabeth Alexander. At the very bottom of today’s newsletter, there’s also an audio of my sermon from last Sunday on the text, “You are the light of the world.”

Last weekend, I preached at Highlands UMC in Birmingham, Alabama. My hosts asked me if there was anything special I’d like to do during my trip. Without hesitation, I replied, “I’d like to visit the lynching memorial.”

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened in 2018. Located in Montgomery, overlooking what was once one of the largest markets of enslaved human beings in the United States, it commemorates the more than 4,400 African-American men, women, and children who “were hanged, burned alive, shot, drowned, and beaten to death by white mobs between 1877 and 1950.”

Those whose names are known are inscribed on massive steel monoliths, all hung from the rafters of a square open-air structure, intended to recall the public squares, trees, and gallows where these acts of racial violence took place.

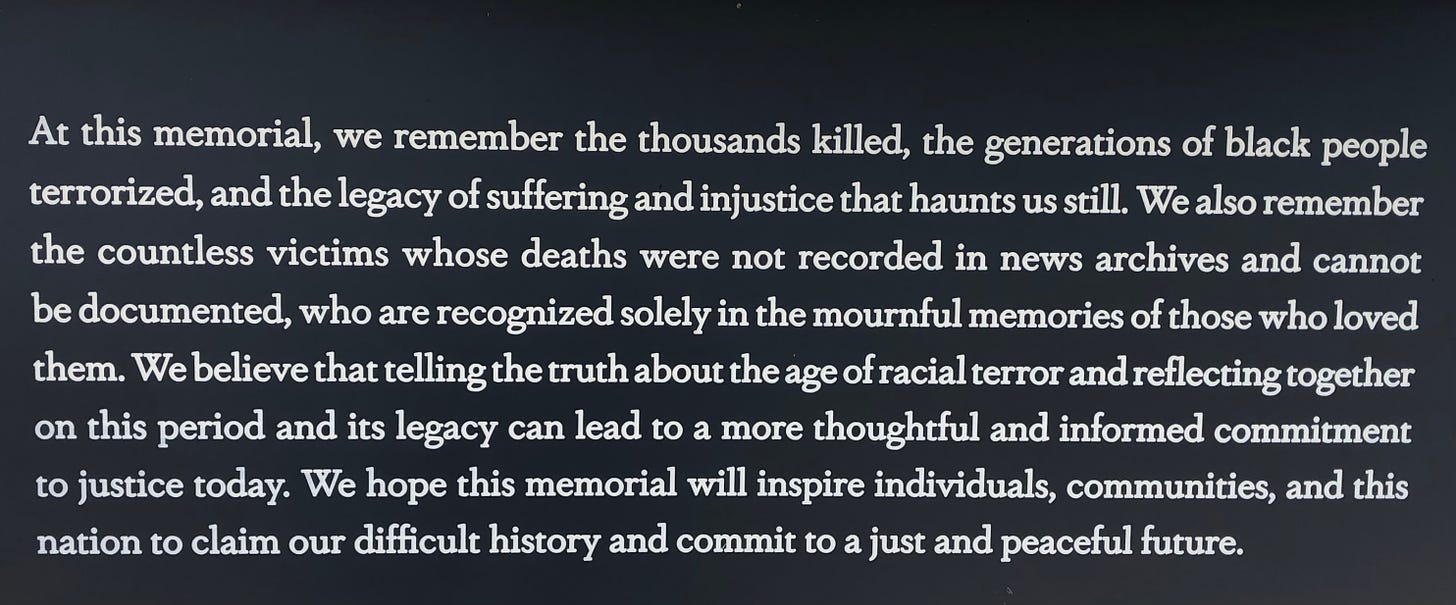

The memorial is one of the starkest public history exhibits in the United States. It is straightforward in presentation and approach. This is a place to confront and reflect on a brutal and inhumane part of the American experience. These words greet visitors at the entry:

As I read these words, I recalled the oft-repeated quote by philosopher George Santayana: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Remembering can be hard. Yet confronting history is necessary.

When I entered the path that leads through the monument, I knew to expect the steel memorials — nearly a thousand of them. Each pillar represents a county or city with the names of all that location’s victims inscribed. Phillips County, Arkansas bears the dubious dishonor of more lynchings — 245 — than any other American county.

The memorial is overwhelming. All those pillars, all those names.

But, for some reason, I was drawn to one: Calhoun County, Georgia.

Most of the victims’ names were male. But this marker bore two female names. Emma and Lillie, both murdered on the same day, December 1, 1884. There was a third person who died that day as well, “Unknown.”

I stared at it for a few minutes, unable to break my gaze. Who were they? Mother and daughter? Sisters? Cousins? What had they done that a frenzied crowd turned on them and killed them in cold blood?

I walked on, slowly, my heart increasingly weighed by the pain of the past. More names, names everywhere. A roster of the unjustly dead, their memories crying out for recognition and justice: We are human beings. We cannot rest until the violence ends. History not only informs, but it burdens us with the moral responsibility to do better, change things.

And I couldn’t get Emma and Lillie out of my mind. At the museum nearby, I asked the guide about them. She showed me how to look them up. We entered their names in the interactive data base and these words appeared on the screen:

After Calvin Mike voted in Calhoun County, Georgia, in 1884, a white mob attacked and burned his home, lynching his elderly mother and his two young daughters, Emma, age 6, and Lillie, age 4.

Emma and Lillie: six and four. Their unnamed grandmother. The ground under my feet seemed to shake, but it wasn’t the earth. It was my body. Unbidden tears flowed down my face.

Lynched babies. Because their father claimed the right to vote granted to him in the United States Constitution. I wanted to reach through time and throw myself between them and the mob; I wanted to save them. I wanted them to grow up to be women, to have their own children and grandchildren. I saw them in my mind’s eye — pigtails waving, wearing cotton dresses with rough wool sweaters against the December chill. Did they clutch dolls as the noose ringed their necks?

Tiny bodies at the end of ropes, swaying in the winter wind.

Six and four.

I guess the mob let Calvin Mike live — to suffer with the memory for the rest of his years. Surely they made him watch.

Emma and Lillie are martyrs. A martyr is someone killed for their beliefs. In this case, the beliefs were that of their father. Calvin exercised his right to vote, to be a man in a democratic nation. He believed that his humanity mattered. He believed in his freedom. That he dared to believe was too much for his white supremacist neighbors. They didn’t martyr him. But they martyred the unnamed woman who birthed him — and the young girls he’d fathered into the world.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is more than a monument. It is a shrine to the martyrs, those who trusted that freedom and democracy were theirs, those who believed in America and in the Beloved Community with their final breaths.

Overhead, their spirits hover, these steely angels reflecting the sunlight, living fully in realms where sound the heavenly strains:

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed.

We have come, over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

Out from the gloomy past,

’Til now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

Long ago, Jesus said, “You are the light of the world.” Set the earth ablaze with justice. The bright star beckons. Go to Alabama. You’ll be blinded by the light of history, the witness of the saints.

INSPIRATION

The wind brings your names.

We will never dissever your names

nor your shadows beneath each branch and tree.

The truth comes in on the wind, is carried by water.

There is such a thing as the truth. Tell us

how you got over. Say, Soul I look back in wonder.

Your names were never lost,

each name a holy word.

The rocks cry out—

call out each name to sanctify this place.

Sounds in human voices, silver or soil,

a moan, a sorrow song,

a keen, a cackle, harmony,

a hymnal, handbook, chart,

a sacred text, a stomp, an exhortation.

Ancestors, you will find us still in cages,

despised and disciplined.

You will find us still mis-named.

Here you will find us despite.

You will not find us extinct.

You will find us here memoried and storied.

You will find us here mighty.

You will find us here divine.

You will find us where you left us, but not as you left us.

Here you endure and are luminous.

You are not lost to us.

The wind carries sorrows, sighs, and shouts.

The wind brings everything. Nothing is lost.

— Elizabeth Alexander, “Invocation”

This poem is posted at the exit of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

LENT AT THE COTTAGE

Ash Wednesday is February 22.

This Lent, The Cottage will explore the EMPTY ALTARS of our days.

We are living in a time of iconoclasm. We've stripped the altars of both state and church. America's spiritual landscape is now marked by empty altars everywhere.

What does it mean to live in such an age? And what comes next? Will we put up new icons? How do we go about that? Can we reimagine the sacred space in which we live?

I’ll be exploring EMPTY ALTARS in TWO WAYS:

1. WEEKLY DEVOTIONAL REFLECTIONS for paid subscribers at The Cottage. Shhh! Don’t tell anyone but Empty Altars is the theme of my next book project — so you’ll be getting a preview of what I’m working on in addition to inspirational material for your Lenten journey.

If you aren’t already a paid subscriber and want to receive the Empty Altars devotional reflections, please upgrade here:

2. An EMPTY ALTARS online class with me and Tripp Fuller. The Cottage and Homebrewed Christianity are teaming up once again for a mind-blowing, heart-expanding class this Lent — and our focus this year is history, spirituality, and social change. The course will begin on Monday, February 27. It requires a SEPARATE SIGN-UP HERE — and is offered for free. Voluntary donations are welcome.

* * *

If you want the ENTIRE EXPERIENCE, make sure you are registered for the class AND have a Cottage paid subscription. The registration and the subscription will give you full access.

Of course, you are welcome to do one without the other — they are complimentary explorations but each is beneficial on its own.

History, despite its wrenching pain,

Cannot be unlived, but if faced

With courage, need not be lived again.

— Maya Angelou

Before visiting the National Memorial, I preached this sermon at Highlands UMC in Birmingham. The text was “You are the light of the world.” Beneath the YouTube is the benediction I wrote and offered at the end of the service.

Closed captioning is available for those find that helpful at the lower right corner after you click to listen.

May God, who is Light and the Maker of Light;

May Jesus, who was born in angelic light to manifest Light;

May the Spirit, who disperses the Light through the earth and the cosmos, enlightening all of God’s people

guide you to be light wherever you go.

Know that you and everyone you meet are of the Light,

and together we can dazzle the world with the brightness of justice and joy.

— Diana Butler Bass

I experienced this many years in Chicago as an activist following 1968 riots following convention. My cousin was at lines in National Guard, said if I wasn’t home with newborn I’d be putting a flower in his at-arms rifle. Many other times I used his name to cross into Chicago PD barricaded neighborhoods because he was a Cook County Sheriff’s chauffeur/bodyguard. Lotsa hate, just my little light shining elsewhere as I push 78th birthday next week. And textbooks, questionable resources (this retired teacher/ First Head Start Family Literacy innovator for up to 1400 families ) are now sought to remove Ruby Bridges from textbooks??? More thoughts our politicos are like a Roman invasion “correcting” history. Urge your elected officials to oppose these idiotic changes lest we relive racial & ethnic tensions of the past. Incomprehensible to me that elected celebrities and suddenly interest parents engage in such awfully energetic causes to deny access to truth.

There aren't words that can express the grief, just tears that cry out, "WHY?" Your article brought back memories of Detroit 1967 and many other places where hate was in full display.